Peapod’s Quiet Quest For Delivery Dominance

Grocery delivery and the Web have a long and checkered history. Today, the move to keep Americans out of the aisles unless absolutely necessary is headlined by some very name-checkable players.

Some of those players are doing a bit of dabbling in grocery delivery as a sideline business — Amazon and Uber most notably. Others — most recognizably Instacart — are in it for the thrills and chills of grocery alone.

And there is much in that checkered history to find both thrilling and chilling. Long before the current wave of online grocery deliverers, there was the previous wave of highly name-checkable luminaries in the same line of work. Back in the late 90s, those names were Kozmo.com and Webvan, and both of those early attempts at same-day delivery blew up when the dot-com bubble burst — collectively taking over a $1 billion in investor funds out with it.

Much has been written about those ultimately failed companies and whether their present-day descendants are fundamentally different (and better) because of mobile and the improvement in logistical management it inevitably brings with it. Everyone loves a good Monday morning quarterbacking session, especially if it includes a section on how much smarter we all are now.

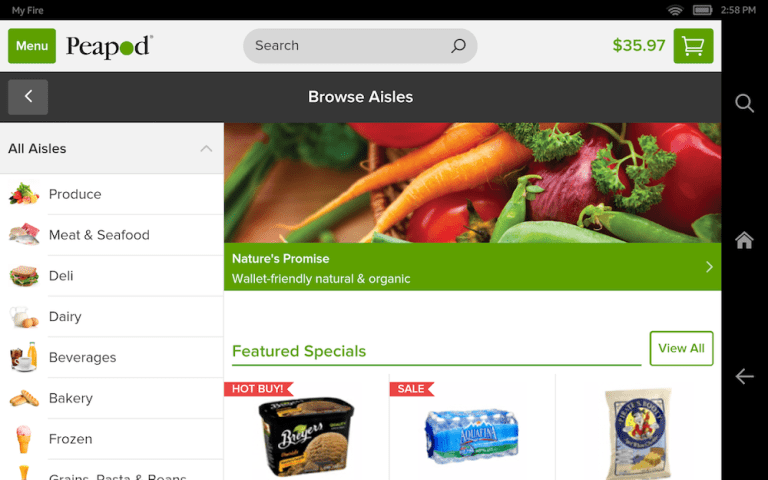

Less has been written, however, about the the grocery on-demand firm from all the way back in the day that actually didn’t fail. Quiet, unobtrusive and yet undeniably effective Peapod.

And while Peapod is sometimes so unobstrusive as to be easily forgotten, it is doing what it has been doing very well for the last 20 years. Quietly making big moves, fattening its margins and flying under the radar, while others rack up headlines (and hit the headwinds).

Don’t believe us?

Why Peapod Is Easy To Overlook (And Why It Shouldn’t Be)

Peapod is a horse of a different color from the rest of what is common in the on-demand delivery market. There is a reason that it often doesn’t get mentioned in the same breath with the biggest players in the online grocery game. Those firms are considered higher-tech, more urban and more millennial-focused. They also almost exclusively serve urban areas, usually starting on the coasts and radiating inward, and are usually headquartered somewhere in Silicon Valley.

Peapod, on the other hand, is based in Skokie, Illinois, and serves a variety of suburban areas in a narrow slice of stores in the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic and Upper Midwest. Having been founded over 20 years ago in Chicago — and owned entirely by Ahold since 2001 — it is by no definition a startup. And it is, generally speaking, not a same-day service; groceries generally need to be ordered at least a day out.

But Peapod is both a player in grocery delivery and a force that upstarts, like Instacart, or insurgents, like Amazon and Google, will have to face off with, particularly as they enter into the ex-urban sweet spots where it has been carving out a fan base for almost two decades.

A quiet fan base perhaps but one that can be observed through steady growth over the last several years, particularly when it comes to basket size.

A decade ago, the average Peapod purchase was a little over $100; these days, the low-end estimate is around $160, and the higher end is over $200.

Basket Size Matters

Compare that to the improvements the Whole Foods/Instacart pair-up brought to basket size, and the significance of that is a little more obvious.

Earlier this year, Whole Foods and Instacart excitedly announced an enhanced partnership — an expansion that was embarked upon at least in part, according to Whole Foods CEO Walter Robb, due to the benefits to basket size from offering delivery on-demand.

Robb told Fast Company that the basket size of Whole Foods customers who shop via Instacart is “substantially larger” than the basket size of customers shopping inside of a Whole Foods. Robb neglected to attach a more specific number to that, though the favorite figure to quote since early 2015 has been 2.5 — as in, the average Instacart basket is 2.5 times larger than the average basket of a brick-and-mortar shopper.

Doubling up is certainly an accomplishment, but notably, that doubling-and-half was never cited in the context of a dollar amount. The temptation — not discouraged by Whole Foods and Instacart — might be to infer that the number would be pretty big, since Whole Foods is lovingly known as “Whole Paycheck” for its exorbitant prices.

Except, not so much. As it turns out, consumers have limited enthusiasm for forking over their whole paycheck for asparagus water. In practical terms, that means the average Whole Foods is actually much smaller than, say, the average basket at Walmart or Costco. Big grocery shops are done at Whole Foods’ lower-cost competitors, while consumers are saving higher-end speciality shopping for the higher-end specialty grocer. All in, the favored estimate is about $54.

If the 2.5 figure still holds from a year ago, the average Instacart/Whole Foods basket clocks in at around $130 — $30–$70 less than the average Peapod basket.

And those differences are extremely important in the tight margin world of grocery delivery.

“Obviously, it’s much better from a profitability standpoint to have a $200 order versus a $100 one,” noted Peg Merzbacher, vice president of regional marketing for Peapod. And digital shoppers are becoming increasingly important to Peapod’s bottom line — as they spend “from two to three times more than even our top shoppers in the store.”

Leveling Up For Enhanced Competition

Being ahead, which Peapod is by many important measures in the grocery delivery game, doesn’t matter much if one can’t stay that way. And that, many have noted, is an increasingly tough challenge when competition isn’t just coming from barely tested startups, like Instacart, but also from power players, like Walmart and Amazon.

Which means Peapod has been undergoing a quiet (as always) technological makeover that involves new warehouse management software, scanners, robotics and miles upon miles of new conveyor belts.

The first major staging ground for the technologically upgraded future, according to Jennifer Carr-Smith, president and general manager of Peapod, will be New York, where Peapod has built a 400,000-square-foot fulfillment center. It is also running someone else’s software — Manhattan Associates Inc. and Dematic Group — instead of building its own, as it usually did in the past.

“In this facility, at this capacity, we needed partners,” said Thomas Parkinson, Peapod’s chief technology officer and cofounder.

Peapod — unlike most firms in search of warehouse management technology — is not, for the the most part, trying to get goods to a loading dock in bulk. Instead, goods must be picked and packaged for each individual order, efficiently.

Which means Peapod’s little green crates travel down seven miles of conveyor belts between customer bays filled with pallets of goods and scanners set to read a barcoded sticker that each unit carries. Associates pick items (and place them in the crates as instructed) as order crates zip along.

Produce is chosen by specially trained employees skilled in picking the perfect tomato, with eggs, milk and other crushables and temperature-sensitive items packed last.

“Food is personal. Shoppers have to know how to pick,” Carr-Smith noted.

The average order contains 50 to 55 items, in six to seven crates, picked from three temperature zones. The customer software selects the crate, the packing order and the movement plan throughout the large and labyrinthine complex in a way the order is put together correctly and quickly.

Crates eventually converge at a designated conveyor lane to be loaded into a truck. The driver gets a manifest showing which numbered crates go to which customer for the 18 to 21 deliveries he does each shift.

It’s hyperefficient, Carr-Smith notes, which is particularly important as grocery margins are getting thinner every day and Peapod’s standard is that every delivery must be profitable for it to make.

Peapod is an old name in a marketplace that loves bright new things. It leverages a warehouse-based model of grocery delivery, despite everyone being sure that, in the age of mobile, such overhead expenses were surely a waste. Why manage a warehouse in a city full of grocery stores and workers ready to grocery shop on-demand?

But, a few years in, Peapod, it seems, has a pretty good answer for that question: controlling that supply chain allows it to service those far-flung suburban customers that are largely out of Instacart’s reach. It also allows it to keep customers happy with a well-run delivery option that, statistically speaking, they want to keep using — and using to make increasingly larger grocery buys.

And, perhaps most importantly, it allows it to continue to actually make money on its service, which others in the on-demand game are realizing is easier said than done in a business as low margin as grocery, with a model as easily imitated as “personal grocery shopper” is.

“It’s tough to make money on every order. When we see others, we just know they’re bleeding cash,” noted Parkinson.