Observations on Anti-Monopoly Developments in China’s Pharmaceutical Industry and Suggestions for Compliance

By Shujun Liu, Lanxue Zhao, Na Li & Xiaoyu Liu1

Ever since the implementation of the People’s Republic of China’s (“PRC”) Anti-Monopoly Law (the “AML”) in 2008, the pharmaceutical industry has been a focus of investigation by China’s anti-monopoly enforcement authority (the “AMEA”). During the anti-monopoly workshop of the National Market Regulation System held in February 2023, the State Administration for Market Regulation (the “SAMR”) proposed to focus on promoting anti-monopoly law enforcement to improve people’s well-being.2 Since then, multiple provincial and municipal governments nationwide have published special action plans for anti-monopoly law enforcement affecting people’s welfare, with the “pharmaceutical industry” appearing in almost all such special action plans. In June 2023, September 2023 and January 2024, the SAMR released the first batch of typical cases, the second batch of typical cases and the third batch of typical cases respectively, totaling thirty-eight (38) cases, as part of their special campaign on anti-monopoly enforcement for people’s welfare of 2023, among which eight (8) cases were relevant to the pharmaceutical industry. 3 In 2024, multiple provincial and municipal governments nationwide redeployed to start a new round of campaigns on anti-monopoly law enforcement concerning people’s welfare, in which, as in 2023, the “pharmaceutical industry” was still the key industry for such law enforcement.

In addition to the anti-monopoly law enforcement efforts in the pharmaceutical industry, on July 21, 2023, the National Health Commission in coordination with the Ministry of Public Security, the SAMR, and seven other agencies, began to implement a year-long initiative on the concentrated rectification of corruption issues in China’s pharmaceutical industry.4 With regard to the anti-monopoly penalty cases previously released by the AMEA, the clues to some of those cases were provided by other administrative authorities. Therefore, it can be expected that the initiative on the concentrated rectification of corruption issues in the pharmaceutical industry will also likely increase the number of anti-monopoly investigation cases in the pharmaceutical industry.

Given the above, companies engaged in the pharmaceutical business in China are facing increased challenges in terms of anti-monopoly compliance. It is against this backdrop that this paper observes the anti-monopoly developments in China’s pharmaceutical industry,5 and provides suggestions for compliance.

I. Anti-Monopoly Legislature

China’s AML was amended on June 24, 2022 and took effect on August 1, 2022 (the amended AML hereinafter referred to as the “New AML,” and the AML before amendment hereinafter referred to as the “Old AML”). Major amendments have been reflected in the New AML, e.g. imposing heavier punishments on illegal activities, adding a “safe harbor,” improving the determination of vertical monopoly agreements, defining the assumption that undertakings must carry the burden of proving that vertical price monopoly agreements6 have no anti-competitive effect, and regulating efforts to organize or aid monopolistic conducts. The supporting regulations were later promulgated and implemented successively under the New Law in 2023.7 In addition, the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council published the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines on the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) Industry8 (the “APIs Guidelines”). Despite the APIs Guidelines having no legally binding effect, these are based on past law enforcement experience in the APIs industry, reflecting the AMEA’s approaches towards enforcement against monopolistic conducts in the APIs industry. These approaches were frequently seen in subsequently released monopoly cases involving the APIs industry.

Additionally, in June 24, 2024, the Supreme People’s Court promulgated the Interpretation on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Monopolistic Civil Cases (the “Judicial Interpretation”), which took effect on July 1, 2024. Compared with the Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Monopolistic Civil Cases Arising from Monopolistic Conducts promulgated in 2012, the Judicial Interpretation mainly contains, among others, the following key amendments: (1) It has expressly stipulated that in a civil anti-monopoly case, a plaintiff may directly invoke the decision made by the AMEA showing that the behavior constitutes monopolistic conduct (provided that such decision has not been subject to any administrative action during the statutory time limit, or has been confirmed by the effective ruling rendered by the people’s court) if the plaintiff asserts that the underlying facts found in the decision are true, with no need to produce evidence (except otherwise overturned by contradictory evidence). (2) The concept of “single economic entity” has been brought into “competitive undertaking” as the essential element of a horizontal monopoly agreement. (3) It has specified that as to the RPM, the defendant bears the burden of proving that the agreement has no anti-competitive effects. (4) An arbitration clause shall not exclude a court’s jurisdiction over monopoly cases.

II. AML Enforcement

A. General Condition of Law Enforcement

1. Types of Monopolistic Conducts Involved

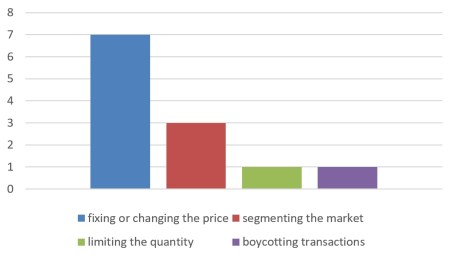

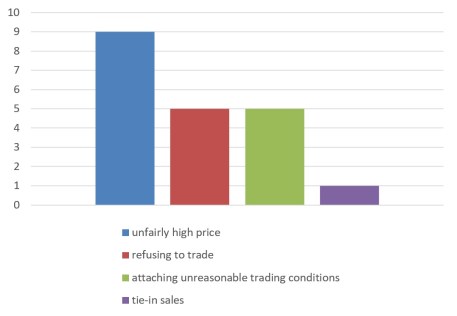

According to incomplete statistics released by the AMEA (excluding cases which have been suspended and terminated), as of the end of July 15, 20249 there were a total of thirty (30) monopoly cases10 concerning the pharmaceutical industry including eight (8) horizontal monopoly agreement cases, seven (7) vertical monopoly agreement cases, and fifteen (15) cases of abuse of dominant market position. Below is the number of monopolistic conducts calculated by type of conduct:

a) Horizontal Monopoly Agreements

b) Vertical Monopoly Agreements

All seven (7) vertical monopoly agreements are RPM agreements.

c) Abuse of Dominant Market Position

2. Segmented Industries Involved

The monopoly cases related to the pharmaceutical industry11 investigated by the AMEA include segments such as APIs, finished drug forms (FDFs), and medical instruments, with nineteen (19) cases involving APIs, nine (9) cases involving FDFs and three (3) cases involving medical instruments (including one (1) case involving both APIs and FDFs).

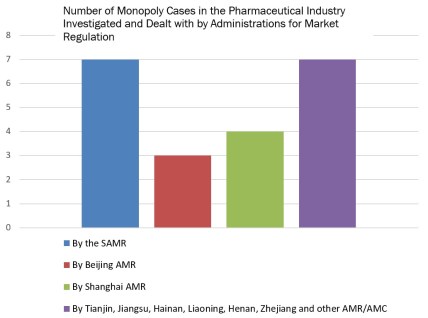

3. Investigative and Enforcement Authority

In March 2018, China reformed its State Council by consolidating AML enforcement functions into the newly established SAMR. In December 2018 the SAMR then empowered its counterparts at the provincial level to investigate and deal with monopoly agreements and abuse of dominant market position cases. So far, the SAMR and its counterparts at the provincial level have investigated and dealt with a total of twenty-one (21) monopoly cases related to the pharmaceutical industry, details of which are provided below:

4. Handling Results

Among the thirty (30) cases mentioned, the maximum ratio of penalty was ten percent (10%) of the previous year’s turnover, and the maximum penalty amount was RMB 764 million yuan. In addition, there were fourteen (14) cases in which illicit proceeds were confiscated, including nine (9) cases of abuse of dominant market position and five (5) cases involving horizontal monopoly agreements. There is no RPM case that involves the confiscation of illicit proceeds. It is also noteworthy that no monopoly case to which the New AML applied has occurred in the pharmaceutical industry.

B. Law Enforcement Approaches Reflected in Monopoly Cases

- Monopoly Agreements

a) Horizontal Monopoly Agreements

Article 16 of the New AML defines a monopoly agreement as any agreement, decision or other concerted practice that eliminates or restricts competition. Pursuant to the Regulations on Prohibiting Monopoly Agreements, the term “other concerted effort” (the “Concerted Practice”) means, in the absence of any express agreement or decision between undertakings, the substantial existence of a form of coordination. A concerted practice shall be determined by taking into account: (i) whether the market practices of the undertakings are consistent with one another; (ii) whether there has been any exchange of intentions or information between the undertakings; (iii) whether the undertakings can reasonably explain the concerted practice; and (iv) the structure, level of competition, and changes of the relevant market. 12

The Estazolam Monopoly Agreement Case is China’s first-ever case of Concerted Practice. With respect to that case, the NDRC decided that Changzhou Siyao Pharmaceutical had concluded and performed a monopoly agreement, for which the NDRC imposed a penalty on it by reason of the following circumstances and facts: (i) not only is the Estazolam APIs market a typical oligopolistic market, the Eszolam Tablets also has become a market where competition is limited as a result of the joint refusal by three (3) concerned companies to provide APIs; (ii) intentions have been shared and exchanged among Changzhou Siyao Pharmaceutical, Huazhong Pharmaceutical and Shandong Xinyi Pharmaceutical (all of them attended the meeting for negotiations over no supply of APIs and joint tablet price increase, and no one has raised express objection nor reported the fact to the AMEA); and (iii) Changzhou Siyao Pharmaceutical’s boycott of transactions and price increase are

consistent with Huazhong Pharmaceutical and Shandong Xinyi Pharmaceutical. That decision indicates that Changzhou Siyao Pharmaceutical has actually concluded and performed a horizontal monopoly agreement involving a concerted practice.

- Conclusion of Horizontal Monopoly Agreements through Third Parties

The Punishment Decision on the Glacial Acetic Acid APIs Monopoly Agreement Case reveals that Jiangxi Jinhan communicated with three (3) concerned companies by telephone on the condition of the glacial acetic acid APIs market, the information regarding their output and sales volumes and their joint intention to raise the price of the glacial acetic acid APIs. All of those three (3) concerned companies expressed their intention to raise the price. Through a series of subsequent discussions and negotiations, those three (3) companies concluded and acted upon monopoly agreements that contributed to an increase in the selling price of the glacial acetic acid APIs, resulting in a fine and confiscation of all illegal proceeds (since the Old AML does not prohibit undertakings from organizing or aiding the efforts to conclude any monopoly agreement, nor does it stipulate any punishment rules, Jiangxi Jinhan has received no punishment). This case shows that any exchange of competitively sensitive information13 or uncompetitive intentions between competitors, whether directly or through any third party, is likely to be determined to be a horizontal monopoly agreement.

b) Vertical Monopoly Agreements

- RPM Restrictions and Major Means to Achieve and Implement RPM

By analyzing the historical penalties for anti-monopoly violations in the pharmaceutical industry, we found that RPM restrictions mainly include: (i) directly setting a fixed or minimum price for resale; (ii) imposing a resale price on the distributors no lower than the guidance price or the discounted guidance price; (iii) setting a fixed or minimum margin for distributors; (iv) setting a fixed or minimum bidding price for distributors; and (v) prohibiting bugsell at a low price.

RPM can be achieved: (i) upon agreement, directly included in a distribution contract; (ii) by entering into a price control agreement; (iii) by sending a letter or notice of price adjustment; (iv) by sending a pricing schedule; (v) through negotiations at a meeting; or (vi) by providing verbal notification.

RPM can be implemented by: (i) establishing a price control system at the company level; (ii) evaluating and supervising internal personnel in implementing the pricing policy; (iii) laying down rewards and punishment for distributor actions; (iv) imposing a punishment on any distributor who fails to comply with the pricing policy; (v) collecting or monitoring, or causing to be collected or monitored, information about the resale price; (vi) imposing restrictions on target customers and sales regions; and (vii) cancelling orders for bid-winning products at a low price.

It is noteworthy that no case in China has been determined to be a vertical monopoly agreement solely by reason of restrictions on target customers and sales regions, while for RPM cases (e.g. the Medtronic Monopoly Agreement Case), restricting target customers and sales regions is often seen as one of the RPM implementation methods that can strengthen anti-competitive effects, and thus can be a factor that results in harsher punishment on the RPM.

- Competitive Effect Analysis of RPM

Paragraph 2 of Article 18 of the New AML provides that “RPM shall not be prohibited if the undertaking can prove that it does not have the effect of eliminating or restricting competition,” that is to say: the burden of proving the agreement has no anti-competitive effects shall be borne by the undertaking. In fact, before any amendment to the AML, the AMEA had consistently adopted the determination rule of “prohibition in principle + exemption under exceptional circumstances” with respect to RPM. Because RPM is essentially a monopoly agreement, the AMEA is not required to prove its anti-competitive effects. However, RPM shall not be prohibited if the undertaking has evidence proving it has not had anti-competitive effects or if it satisfies any of the exemption conditions provided in Article 15 of the Old AML. A similar determination rule has been adopted for the punitive decisions on the Yangtze River Pharmaceutical Monopoly Agreement Case and the Zizhu Pharmaceutical Monopoly Agreement Case.

c) Abuse of Dominant Market Position

- Definition of the Relevant Market

The prerequisite for an undertaking to constitute an abuse of market dominant position is that the undertaking has a dominant market position. Thus, the definition of the relevant market and determination of a dominant market position are of utmost importance. Among fifteen (15) cases of abuse of dominant market position in the pharmaceutical industry that have been investigated and dealt with, thirteen (13) cases were related to the APIs market, and two (2) cases to the FDF market.

Regarding anti-monopoly enforcement practice in China, it is normally necessary to define the relevant market as the relevant product market and the relevant geographic market through substitutability analysis, including demand substitutability analysis and supply substitutability analysis.

As for the definition of the relevant APIs market, according to the anti-monopoly enforcement practice and the APIs Guidelines, since APIs play a special role in drug manufacturing, a standalone product market normally exists for a specific type of API and can be further segmented as required. Different types of APIs that can be substituted for one another can also be part of the same relevant product market. Based on the actual situation, the relevant product market may be further segmented into the APIs manufacturing market and the APIs distribution market. The relevant geographic market for APIs manufacturing and distribution is normally defined as China market. Among the existing enforcement cases so far, when it comes to the definition of the relevant market for APIs, a specific type of API often constitutes a standalone relevant product market, and the geographic market is defined as China market.

As for the definition of the relevant market for FDFs, given the limited number of anti-monopoly enforcement cases so far, and the absence of relevant guidelines, it remains unclear how the relevant market is being defined.

Nevertheless, according to our experience with the anti-monopoly cases involving the FDFs industry we understand that, firstly, the relevant product market for FDFs needs to be defined based on demand substitutability. Drugs are distinguished and classified based on indications, thus indications become the primary factor to be considered by the AMEA in determining demand substitutability among different types of drugs. A set of drugs with the same indications can constitute a standalone relevant product market, which can be further segmented as required. Furthermore, the ingredients and mechanism of action, dosage form and dose intensity, side effects, physicians’ prescribing habits, and whether these drugs are in shortage, may also be considered by the AMEA in determining demand substitutability among different types of drugs. Secondly, if necessary, supply substitutability analysis may be conducted by considering such factors as market entry, production capability, product facility renovation and technical barriers. In addition, based on the actual situation, the relevant product market may need to be further segmented into the drug manufacturing market and the drug distribution market. When defining the relevant geographic market for FDFs, the qualifications and regulatory standards for drug manufacturing and distribution can vary by country. A drug undertaking that manufactures or distributes drugs in China is required to organize manufacturing activities by following the approved processes, strictly comply with the quality management standards for drug manufacturing and drug business operation, and ensure its manufacturing activities and business operations conform to statutory requirements. Importing drugs too requires the approval of China’s regulatory authority. Therefore, the relevant geographic market for FDFs is normally defined as the full national market in China.

As for the definition of the relevant market for medical instruments, currently, no case of abuse of dominant market position has been released, and same as FDFs, no relevant guidelines have been published yet. We are aware that the relevant market for medical instruments needs to be defined on a case-by-case basis and in line with the AML and the general principles set out in the Guidelines on the Definition of the Relevant Market by the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council.

- Determination of Joint Dominant Market Position

Article 24 of the New AML provides that undertakings can be presumed to have a dominant market position if the combined market share of two undertakings accounts for two thirds (2/3) of the relevant market, or when the combined market share of three undertakings accounts for three fourths (3/4) of the relevant market (with the caveat that an undertaking whose market share is less than ten percent (10%) shall not be presumed to have a dominant market position).

Among the cases of abuse of dominant market position in the pharmaceutical industry, there were two (2) cases in which two undertakings were determined to have a dominant position in the relevant market. In the Case of Abuse of Dominant Market Position by Isoniazide APIs Companies, the NDRC presumed that two (2) companies were in a dominant market position by reason of their combined market share of more than two thirds (2/3) of the market along with their respective market share of no less than ten percent (10%); however, in the Case of Abuse of Dominant Market Position by Chlortrimeton APIs Companies, the SAMR presumed that two (2) companies were not only in a dominant market position by virtue of their combined market share of more than two thirds (2/3) of the market and their respective market share of no less than ten percent (10%), but also in a joint dominant position in the chlortrimeton APIs market because of their close relationship (that is, one company had the power to import chlortrimeton APIs and exercised control over the other company with potential acquisition intent and actual influence, and both companies coordinated with each other on concerted practices).

The latter determination rule was also reflected in the Interim Provisions on Prohibiting Abuse of Dominant Market Position issued by the SAMR in June 2019, i.e. whether two or more undertakings maintain a dominant market position shall be determined by taking into account such factors as market structure, the transparency of the relevant market, the degree of homogeneity of the relevant products, and the presence of concerted practices between undertakings.

Furthermore, in the Case of Abuse of Dominant Market Position by Calcium Gluconate APIs Companies, and the Case of Abuse of Dominant Market Position by Polymyxini B Sulphas for Injection, the parties to such cases were determined to have jointly abused their dominant market position through division of work and close collaboration agreements (without the need to determine their respective dominant market positions).

d) Types of Abuse

- Unfairly High Prices

Unfairly high prices in the pharmaceutical industry are mainly reflected in the following ways: (i) the range of selling price increase is abnormal when the costs and downstream demand are basically stable; (ii) the price increase is significantly greater than the cost increase; (iii) the selling price is significantly higher than that offered by other undertakings under the same market conditions; (iv) the selling price is significantly higher than the purchase price; (v) the selling price is significantly higher than any historical price; and (vi) the price has repeatedly increased through intra-company transactions and circulation of bills.

- Unjustified Refusal to Trade with the Relevant Counterparty

Any of the following acts, when committed by an undertaking, may be considered unjustified refusal to trade with a relevant counterparty in the pharmaceutical industry: (i) selling products only to the exclusive sales trader or any of its designated undertakings upon execution of an exclusive sales agreement, and refusing to sell products to any other undertakings; and (ii) offering trading conditions that the relevant counterparty can hardly accept (e.g. a large deposit payment, selling FDFs back to the APIs company, and obtaining commissions by requesting price increases by the FDFs company), as a disguised form of refusal to trade.

- Unjustified or Unreasonable Trading Conditions

In the pharmaceutical industry, an undertaking attaches unreasonable trading conditions without justification, mainly by: (i) requiring the relevant counterparty to purchase products beyond the actual demand; (ii) collecting an unreasonable consideration without providing relevant services; (iii) should the undertaking be an APIs company, requiring any downstream FDFs company to sell products back to itself or serve as its own foundry; (iv) requiring a large deposit payment; and (v) sharing the profits from FDFs.

- Unjustified Tie-in Sales

Unjustified tie-in sales in the pharmaceutical industry mainly take place in the following manners: (i) APIs; (ii) pharmaceutical necessities, packaging materials, and medical instruments; (iii) FDFs; and (iv) other products.

III. Judicial Anti-Monopoly Cases

Despite the limited number of judicial anti-monopoly cases in the pharmaceutical industry as compared with anti-monopoly enforcement cases, the following representative cases have clarified specific adjudication approaches and are of great guiding significance in practice.

A. Adjudication Approaches Towards Determining Whether the Reverse Payment Agreement on a Drug Patent is Suspected of Being a Monopoly Agreement

Article 20 of the Judicial Interpretation mentioned above provides that a reverse payment agreement on drug patent may constitute a horizontal monopoly agreement.14 With regard to the case over invention patent infringement involving the reverse payment agreement on patent relating to salagliptin tablets, the Supreme People’s Court held that the judgment on whether the reverse payment agreement on drug patent is suspected of being a monopoly agreement subject to the AML depends on whether such agreement is suspected of eliminating or restricting competition on the relevant market. So far, this is China’s first-ever case in which the court has rendered a decision on anti-monopoly review of the reverse payment agreement on drug patent. Although such anti-monopoly review is merely a preliminary review with respect to the request for withdrawal of appeal, and in light of the actual situation of the case, it remains uncertain whether the concerned settlement agreement constitutes a violation of the AML, the decision also emphasized the necessity to, during the trial of the case, properly conduct in due time an anti-monopoly review of the agreement by virtue of which the party to a non-monopoly case asserts claims, and indicated the degree and basic means of the review of the reverse payment agreement on drug patent.

B. Adjudication Approaches Towards Dealing with the Relations between IP Protection and Anti-Monopoly

In the case of abuse of dominant position in the market for desloratadine citrate disodium APIs, Yangtze River Pharmaceutical (Group) Co., Ltd. and its subsidiaries (collectively “Yangtze River Pharmaceutical”) alleged as plaintiff that Hefei Medical and Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and its subsidiaries and affiliates (collectively “Hefei Medical”) was the only supplier of the APIs concerned, and that they were competitors with respect to the FDFs concerned. Hefei Medical employed its dominant position in the APIs market involved in the case to require Yangtze River Pharmaceutical to purchase the APIs concerned solely from it, to significantly raise the price of the APIs concerned, and to force Yangtze River Pharmaceutical to accept other commercial arrangements irrelevant to the concerned APIs transaction by threatening to cease the supply of the APIs concerned.

The Supreme People’s Court held in the second-instance trial that, despite Hefei Medical’s dominant position in the domestic market of the concerned APIs in China, the company is also facing indirect and tough competition from participants in the downstream FDFs market, thus its dominant market position has diminished to a certain extent, and existing evidence is insufficient to prove that it has abused such dominant market position. Firstly, since the APIs concerned have fallen into the scope of the patent protection of Hefei Medical, it is Hefei Medical’s legitimate right to require Yangtze River Pharmaceutical to purchase the APIs concerned solely from it during a specified period and to a certain extent, and the market blockade effects resulting from this have not gone beyond the scope of legal patent exclusivity. Thus, Hefei Medical’s behavior does not constitute an unjustified restriction on trading. Secondly, considering the internal rate of return upon price increase and the degree of matching between price and economic value, it is highly possible that the APIs concerned were originally sold at a promotional price, and any subsequent and significant price increase can be a reasonable adjustment of the promotional price to a normal price. Thus, the price increase that is significantly higher than the cost increase alone is insufficient to constitute an unfair high price. Thirdly, existing evidence is insufficient to prove that Hefei Medical has expressly or implicitly tied any project irrelevant to the case to the sale of the APIs concerned, rendering it difficult to determine that unreasonable trading conditions have been attached.

By defining the following factors to be considered, this case plays an active role in properly dealing with the relations between patent protection and anti-monopoly: (i) the impact of indirect competition from the downstream market on the intermediate goods operator’s dominant market position, (ii) the correlation between and judgment methods for the market blockade effects resulting from the trading restrictions and the exercise of patent rights, and (iii) the determination and regulation of unfairly high prices and attachment of unreasonable trading conditions..

IV. Compliance Suggestions

Pharmaceutical companies are advised to pay attention to the following monopoly risk management and compliance matters.

A. Prevent Monopoly Agreement Risks

- Prevent Horizontal Monopoly Agreement Risks

In principle, a pharmaceutical company shall refrain from any business contact with its competitions. If an employee of the pharmaceutical company would inevitably have any contact with any of its competitors due to the necessity to attend any meeting that the competitor also attends or any other special reason, the employee shall, in line with the filing and reporting mechanism, file the case in advance for record within the company, and report afterwards the relevant details within the company. When meeting with the competitor for any reason whatsoever, the employee shall not exchange with the competitor any competitively sensitive information (e.g. future price information, cost, market and client information, bids and tenders) that is likely to cause monopoly agreement risks, nor shall he or she conclude any agreement or make any decision in relation thereto. When the competitor takes the initiative to mention any competitively sensitive information, the employee shall make it clear to the competitor that he or she has no intention to conduct such exchange in any form, and shall immediately end the conversation about the topic, voluntarily excuse himself or herself and timely report the case to the Compliance Department of the company.

The pharmaceutical company shall conduct business operations and set prices in an independent manner, and shall ensure that price adjustment and other business decisions be made on its own.

- Prevent Vertical Monopoly Agreement Risks

The pharmaceutical company shall refrain from concluding and performing any vertical monopoly agreement with its distributors, including: (i) concluding a monopoly agreement that sets a fixed or minimum resale price by entering into agreements with tier-1 distributors and tripartite agreements with tier-1 and tier-2 distributors, or giving a letter of price adjustment or price maintenance notice or otherwise; and (ii) performing a monopoly agreement that sets a fixed or minimum resale price by refining its sales management system, or entrusting a data provider or otherwise.

- Refrain from Organizing Other Undertakings to Conclude a Monopoly Agreement or Providing Substantial Assistance for That Purpose

The pharmaceutical company shall refrain from calling on its competing undertakings to conclude any horizontal monopoly agreement, and from providing any upstream supplier, downstream customer or other competing undertakings the opportunity to exchange intentions or information with each other for the purpose of concluding a horizontal monopoly agreement, either at a meeting or by virtue of any agreement. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical company shall refrain from facilitating the conclusion of any horizontal or vertical monopoly agreement by any other undertakings.

B. Prevent the Risks of Abuse of Dominant Market Position

The pharmaceutical company is advised to conduct a dynamic assessment of the market strength of its business. When the company has a relatively large market share and has strong capability for market control, particularly if the company is the only marketing license holder of a certain type of drug, then it is highly likely that the company has a dominant market position over the relevant market. In such cases, the company needs to refrain from abusing its dominant market position by: selling APIs or FDFs at an unfairly high price; and in the case of the APIs company (i) requiring FDFs companies to sell FDFs to it at a low price; (ii) requiring FDFs companies to offer rebates to it in the form of promotional fees, R&D fees, service fees or otherwise; or (iii) requiring FDFs companies to sell FDFs in certain region and at certain price as designated by it; or (iv) refusing to trade with the relevant counterparty in disguised form through any of the said methods.

Click here for the full article.

1 Global Law Office, China. https://www.glo.com.cn/en/.

2 https://www.samr.gov.cn/jzxts/sjdt/gzdt/art/2023/art_8b6c6fb2d52e44519cdbccc602e5e645.html.

3 Details of the first batch of typical cases: https://www.samr.gov.cn/xw/zj/art/2023/art_9590c83509dd448cb2385a2459661715.html; Details of the second batch of typical cases: https://www.samr.gov.cn/fldys/sjdt/gzdt/art/2023/art_f49c6fd3b75044cb8d510881e466c7fa.html; Details of the third batch of typical cases: https://www.samr.gov.cn/xw/sj/art/2024/art_91953f3d611f4195b5cbfade261994fa.html.

4 http://www.nhc.gov.cn/ylyjs/pqt/202307/7baafcfccc244af69a962f0006cb4e9c.shtml.

5 This paper mainly focuses on the anti-monopoly compliance matters in the day-to-day operation of any company, thus the dynamic observations on the concentrations of undertakings are not discussed herein.

6 From the perspective of a vertical monopoly agreement, monopolistic conduct regulated by China’s Anti-Monopoly Law is mainly divided into two categories:

(1) Pricing vertical restrictions: means the practice of setting a fixed or minimum price for resale of products to any third person. To simplify the expression, sometimes in this paper, the term “pricing vertical restrictions” is also called “resale price maintenance” (RPM).

(2) Other non-pricing vertical restrictions: In current practice, attention-getting and high-risk behaviors include restrictions on target consumers and sales regions (generally speaking, prohibiting or restricting bugsell), and restrictions on supply channels.

7 On March 24, 2023, four (4) supporting regulations under the AML were promulgated by the SAMR, i.e. the Regulations on Prohibiting Monopoly Agreements, the Regulations on Prohibiting Abuse of Dominant Market Position, the Regulations on Review of Concentrations of Undertakings, and the Regulations on Prohibiting Abuse of Administrative Powers to Eliminate or Restrict Competition, all of which took effect on April 15, 2023.

On June 25, 2023, the SAMR promulgated the Regulations on Prohibiting Abuse of Intellectual Property Rights to Eliminate or Restrict Competition, which took effect on August 1, 2023.

On January 22, 2024, the Regulations of the State Council on Thresholds for Declaration of Concentrations of Undertakings was promulgated, which took effect on the same day.

So far, all six supporting regulations to the New AML have been promulgated and in force.

8 https://www.samr.gov.cn/zw/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/fldj/art/2023/art_41fb5140a72f4283bb62aa7fff3d53e4.html.

9 In the absence of special notes, the number of the AML enforcement cases in the pharmaceutical industry is calculated as of this date.

10 Among such cases, there was one (1) case in the APIs industry that simultaneously involves the horizontal monopoly agreement and the abuse of dominant market position, which has been counted by us as two cases statistically.

11 Including one (1) case in the pharmaceutical industry that involves both the APIs and the FDFs, which has been counted by us as two cases statistically.

12 There are similar provisions contained in the Anti-Price Monopoly Provisions previously promulgated by the NDRC (effective as of February 1, 2011 and repealed on August 26, 2019).

13 According to Paragraph 3 of Article 14 of the Guide to the Anti-monopoly Compliance of Undertakings (No. 4 [2024] of the Anti-Monopoly and Anti-Unfair Competition Commission) promulgated by the Anti-Monopoly and Anti-Unfair Competition Commission of the State Council on April 25, 2024 which came into effect as of the same day, the “competitively sensitive information” mentioned herein refers to the costs, prices, discounts, quantities, qualities, turnovers, profits or profit margins of the goods, as well as the undertakings’ research and development, investments, production, marketing plans, customer lists, future business strategies and other information closely related to market competition, except for information that has been publicly disclosed or can be obtained through open channels.

14 Article 20 of the Judicial Interpretation provides that if the plaintiff has evidence that the agreement concluded and implemented by a generic drug applicant and a patent holder of a brand-name drug meets all of the following conditions, and asserts that such agreement constitutes a monopoly agreement under Article 17 of the Anti-Monopoly Law, such assertion may be supported by the people’s court:

(1) The patent holder of the brand-name drug gives or promises to give the generic drug applicant manifestly unreasonable money or any other form of benefit as compensation; and

(2) The generic drug applicant promises not to challenge the validity of the patent right of the brand-name drug or to delay the entry into the relevant market of the brand-name drug.

If the defendant has evidence that the compensation referred to in the preceding paragraphs is solely used for covering the costs incurred in resolving the dispute over the patent of the brand-name drug or for any other purpose with justified reasons, or the agreement complies with the provisions of Article 20 of the Anti-Monopoly Law, and contends that the agreement does not constitute a monopoly agreement under Article 17 of the Anti-Monopoly Law, such contention shall be supported by the people’s court.

Featured News

Belgian Authorities Detain Multiple Individuals Over Alleged Huawei Bribery in EU Parliament

Mar 13, 2025 by

CPI

Grubhub’s Antitrust Case to Proceed in Federal Court, Second Circuit Rules

Mar 13, 2025 by

CPI

Pharma Giants Mallinckrodt and Endo to Merge in Multi-Billion-Dollar Deal

Mar 13, 2025 by

CPI

FTC Targets Meta’s Market Power, Calls Zuckerberg to Testify

Mar 13, 2025 by

CPI

French Watchdog Approves Carrefour’s Expansion, Orders Store Sell-Off

Mar 13, 2025 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – Self-Preferencing

Feb 26, 2025 by

CPI

Platform Self-Preferencing: Focusing the Policy Debate

Feb 26, 2025 by

Michael Katz

Weaponized Opacity: Self-Preferencing in Digital Audience Measurement

Feb 26, 2025 by

Thomas Hoppner & Philipp Westerhoff

Self-Preferencing: An Economic Literature-Based Assessment Advocating a Case-By-Case Approach and Compliance Requirements

Feb 26, 2025 by

Patrice Bougette & Frederic Marty

Self-Preferencing in Adjacent Markets

Feb 26, 2025 by

Muxin Li