Physical Retail’s Data Distortion Trap

In 1907, Mark Twain famously popularized the saying “lies, damn lies and statistics,” almost as a self-deprecating comment about his own ability to interpret “figures” when writing about them. An expression first attributed to British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, today it’s often used to describe the use of data to support any argument on a topic.

Take, for instance, Black Friday 2021, where consumers shopped for deals.

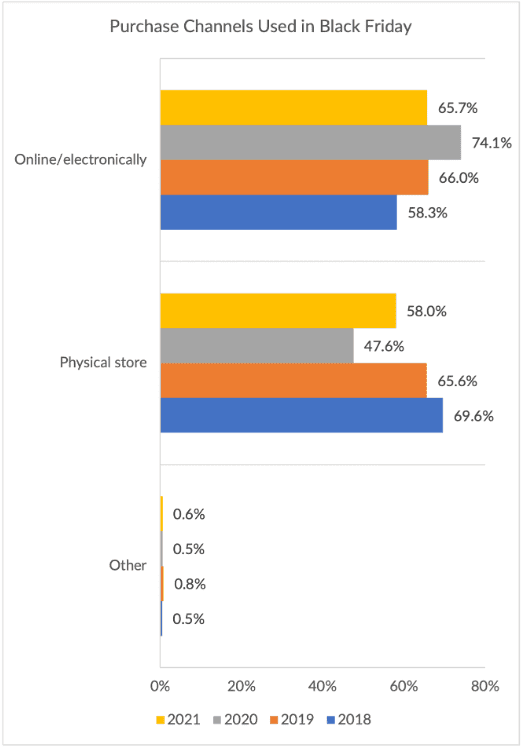

Initial reports on the heels of this holiday shopping tradition almost literally screamed “physical stores are back,” showing more consumers shopping in physical stores in 2021 than they did online.

I guess that depends on how one defines “back.”

As a discrete data point, and when compared to 2020, more consumers did shop in stores than online.

As a discrete data point, and when compared to 2020, more consumers did shop in stores than online.

But that is very different than implying that shoppers are shopping at physical retail as much as they did pre-pandemic.

See Also: Black Friday Report

In 2021, according to PYMNTS’ fourth annual Black Friday study, a smaller fraction of shoppers did their Black Friday shopping in physical stores in 2021 than in 2019.

In fact, in 2021, there was almost a 12% drop in shopping at physical stores on Black Friday than in 2019.

And it’s not as if 2019 was a high-water mark for in-store shopping, either. Digital has been eating into holiday shopping in the physical store since 2013.

See also: The Coming Decline of Physical Retail

According to PYMNTS’ holiday shopping research of a population-based sample of 2,060 consumers on Nov. 27, 2021, consumers say they’ll do about half of their remaining holiday shopping online. And that was before Omicron and the uncertainty associated with the severity of the latest COVID variant, which could push that higher.

For consumers, the digital shift is no big deal. It’s increasing how they roll.

Consumers have become quite fluent in shopping online – mostly because the merchants they shop with have made it an easy, seamless and friction-free experience. Of course, physical retail isn’t irrelevant, and consumers still shop in stores as well as online. But how – and how often – they use the physical store is changing.

Stores are becoming showrooms where consumers go to look but maybe not buy, and fulfillment centers to pick up what they bought online and need sooner than the store can deliver it. Direct-to-consumer (D2C) brands are opening physical storefronts to sell things, of course, but more so to advertise their presence in key geographies to consumers who see their brand online and can go into the store to buy or browse and bring their friends – and vice versa.

How consumers experience the physical store now will determine how they use it going forward – especially as the online shopping experience continues to improve.

The Integration of Digital Into the Physical World

It’s not just shopping in-store that’s in the crosshairs of the digital shift.

As you’ve read on these pages over the last two years, consumers are openly embracing the digital integration of what were once largely physical activities into their daily lives.

How consumers bank, work, shop, stay well, pay and are paid, have fun, travel, communicate, eat and live in their homes are now highly influenced by how they use connected devices and apps to engage in those activities.

But just as Mark Twain admonished, it’s easy to look at the data, just as many did for Black Friday, and say that physical remains dominant in what consumers do on a day-to-day basis.

That would be misleading: In fact, it is the trap that physical retailers fell into when they kept saying, “yeah, I get this internet thing, but consumers buy 95% of retail as physical stores” — until they didn’t.

Take grocery shopping, for example.

PYMNTS’ latest data on consumers and the connected economy from a study conducted in November of 2021, based on responses from 3,166 U.S. consumers, shows that roughly 91% of consumers still shop in a physical grocery store at least once a month, and roughly two-thirds of consumers shop in a physical grocery store once a week.

This data also shows that 15% of consumers shop for groceries online and pick up curbside, 13% shop online and have groceries delivered, 14% shop online using Instacart for delivery once a week and 12% ordered online and picked up in the store.

Just three years ago, those online numbers are in the teeny single digits.

In the space of three years – and not just because of the pandemic and fears over COVID – online grocery shopping has become part of the consumer’s grocery routine, particularly for the millennials and bridge millennials who represent the grocery store’s future customers.

Take telehealth.

This same PYMNTS data set shows that roughly 51% of consumers saw a doctor, went to a clinic or received healthcare services at a retail location (think urgent care or vaccinations) and/or picked up a prescription there in the last month. Over that same period, 40% of all consumers accessed a telehealth service for their physical health, even more millennials and bridge millennials did, and 21% of consumers used a website or app to order their meds for pickup or delivery.

Telehealth has been around for more than a decade, and before the pandemic, just like digital grocery shopping, only a small handful of consumers used it. But just like digital grocery, this once largely physical activity is now moving to digital out of convenience, and because of the access to telehealth that something as basic as a smartphone now enables. Innovators are using technology to further extend telehealth’s utility into the home as the enabling platform for the in-home healthcare shift.

All this is to say that the digital economy is scaling, and quite quickly, as both a complement to and a replacement for physical interactions. New ecosystems are emerging to simplify and streamline how consumers can move easily between the online and the offline worlds.

At the same time, businesses are using technology to adapt to consumer behavior and to survive. The digital transformation helped them make it through the pandemic, and in some cases thrive. Today, technology and digital payments help businesses address labor shortages, create efficiencies and mitigate margin pressures due to the increased costs associated with running their businesses.

It’s a shift that has implications for businesses, regulators and lawmakers alike as consumers increasingly make known their digital preferences – and their preferences for who delivers their connected digital experience.

The Connected Consumer

According to the latest PYMNTS ConnectedEconomyTM research conducted in November of 2021, 67% of all U.S. consumers are interested in living in a more connected digital economy. That’s up slightly from our April 2021 study. More than a fifth of U.S. consumers say they are very or extremely interested.

Per a PYMNTS report to be released in mid-December, we are starting to see different connected consumer personas emerge and gain insight into how they may want some or even all of their daily activities integrated in a single ecosystem for ease, convenience and security.

More than a third of the consumers we studied would like to have a single app for managing their financial, bank account and payments information; one in five would like a single ecosystem for managing their shopping and entertainment activities. More consumers are concerned about linking their bank account details to a single ecosystem than integrating their health and wellness activities into one. The integration of payments into a “super app” is a feature that 47% of consumers we studied say they would find valuable.

PYMNTS research from April 2021 tells us that one of the appeals of living in a more connected digital world is the desire to control their personal information – consumers believe that being part of a connected ecosystem gives them more control over who sees what and when.

Importantly, consumers who want to live in a more connected digital economy also say that they feel their data is more secure there. Two-thirds of those with an interest in living in a more connected economy say they don’t want their usernames and passwords all over the web – having credentials in one place makes them more comfortable. These are the same consumers who say they trust Big Tech and FinTechs — in particular, Amazon, Apple, Google and PayPal — to enable a more connected ecosystem, because their interactions with them have been safe, secure and private.

Clearly, consumer adoption of a digital and more connected economy will be driven by innovators who will identify discrete points of friction in the physical world and create digital solutions that solve for them. Much of this will include the efforts by startups who hope to become a feature or an enabling technology that accelerates the connected ecosystem’s potential. The use of technology to make the connected ecosystems that consumers already see as valuable even more secure, personalized and robust is already evident in the number of new ventures being funded to enable and enrich these experiences.

Often, the motivation is that they will be acquired by one of the platforms or ecosystems for which they add value. That makes sense, because these platforms/ecosystems have created massive communities that these innovators could not replicate with their feature innovations, and these platforms/ecosystems can’t be expected to come up with every innovation themselves. There’s a gain to trade.

Lawmakers and regulators need to be careful that in their quest to reign over Big Tech, the entrepreneurs behind these innovations and the consumers who want to live in a super-app world don’t end up with the short end of the stick. It may be better to figure out other ways to keep Big Tech in line than making it hard for them to develop and offer digital products in the connected ecosystems they power.

At the same time, there needs to be a balance between what was considered a “pandemic exception” such as what we see now in telehealth, and the consumer’s desire to make it part of their connected world.

Measuring the Data That Matters

In what will now be a monthly benchmarking of how consumers live in a connected digital economy globally, PYMNTS is building on the work done over the last 18 months to document how consumers want to live in a world in which physical is an extension of their digital experience and not the other way around – and who they trust to enable those experiences.

The goal is to establish a consistent, reliable dataset consistent with the intellectual framework that defines the connected economy, and one that reflects the inevitability of a more connected digital world.

The implications for business decision-makers are obvious, as those across each of the pillars of the connected economy plan their own strategic digital transformation and make decisions to build, partner or buy the capabilities needed to deliver what consumers now want and use.

So, too, will be its utility for policymakers and lawmakers as they wrestle with getting the balance of innovation and regulation just right – to avoid the trap of using just any data to decide the future of the digital connected economy just as it now so clearly shows its potential.

See Also: TechReg Chronicle: Regulating the Digital Economy