How Netflix Shows the Importance of Getting Innovation’s Timing Right

There Are Ghosts, of Course

A bit more than 25 years ago, on March 10, 1998, Netflix shipped its first DVD, “Beetlejuice,” about two ghosts played by Alec Baldwin and Geena Davis. Last Friday, more than 5.2 billion DVDs later, it shipped the last one. Netflix is all in on its pioneering streaming subscription service, which it launched in 2007 at the start of its second decade in business.

These disruptive innovations in the media business owed a lot to timing.

When Netflix started, people trekked to their local video store to get bulky VHS tapes and went back again to return them. Customers paid hefty late charges if they didn’t get them back on time. Given their size and fragility, starting a mail-order video company with VHS would be tough. But along came DVDs. The players began selling in March 1997 and were rapidly adopted by households. Netflix saw the opportunity to create a mail-order subscription business that sent out slender, durable DVDs and customers could just pop them in the mail to return them.

Netflix could have launched — also, or instead of — a streaming service. RealPlayer launched a couple of years earlier, making it possible to watch videos over the internet. If Netflix had, it would have been a bust. Most people were using slow dial-up modems and broadband speeds were slow.

Fast forward to 2007 and more households had broadband connections; by 2009, about 40% had Wi-Fi networks. Slow by today’s standards but wicked fast compared to dial-up, it was possible to enjoy movies streamed over the internet. Broadband speeds grew rapidly as did its uptake, making high-quality streaming available to most households.

Netflix placed a huge bet on streaming. It paid upfront for rights to stream a large catalog of movies and television shows in the US. “The Field of Dreams” — build it and they will come — worked and the rest is history.

Its mail-order DVD innovation is widely credited with helping put physical video stores like Blockbuster out of business. However, its streaming innovation was far more important. By itself, and through follow-on entry by players such as Prime Video, Netflix led to the nosedive in cable subscriptions, emptied movie theaters and changed many of the business dynamics of producing and monetizing television and movies.

Today, Netflix has a market cap of about $170 billion.

It’s About the Timing

Some entrepreneurs may just, like the proverbial Apple falling on Isaac Newton’s head, come up with a brilliant idea and run with it. Most are in the business of searching for the next great opportunity. As are wannabee innovators at large companies. If you want to succeed at that, you have to get the timing right.

That’s particularly true for digital businesses who depend on complementary technologies being developed or being far enough along, to make profitable ignition and growth possible.

Or who require changes in customer behavior that they can’t force themselves.

That requires knowing not just whether a complementary technology will be developed or customer behaviors will change but when and how rapidly.

That was not so hard for Netflix when it started. The DVD player and discs were introduced in Japan in 1996 and were launched in the US in 1997. By 1999, it was reasonably clear the sleek players and capacious CD-like discs would displace bulky VHS players and tapes.

It was also obvious that streaming was not ready for prime time. It would take years for cable systems to lay broadband and for households to adopt it. Transmission speeds were low and latency high. But technological progress in broadband and investment decisions by cable companies also made it clear that there would be a future in streaming.

In 1995, RealNetworks launched its innovative media player, making it easy for people to stream audio and video over the internet. And it started a music and video content business at the end of 2001. There was nothing wrong in doing this, given the business they were in. But the timing worked against them. And the 2000s became the decade of the iPod and iTunes. Today, the market cap of RealNetworks is about $35 million, down from a post dot.com crash peak of $1.8 billion in November 2006.

Ultimately, Apple got the timing wrong, too, by not recognizing the power of streaming music over mobile devices with fast mobile and fixed broadband speeds. With iTunes on the rope, because of Spotify and other streaming music providers, it launched its own streaming service, Apple Music, in 2015.

Apple did OK.

The digital transformation is littered, however, with failed or shriveled companies whose principal failing is getting the timing wrong and being too early to the party. Or too late.

Managing Complementary Inputs in the Face of Dynamic Competition

Sometimes, no one’s to blame for getting the timing wrong.

Before 2007, it was possible to predict that smartphones would get much better and benefit from the widescale deployment of 3G networks. Even Google, working intensely on launching Android, was dumbfounded when it saw the iPhone. Once iPhones and recalibrated Android phones became widely available, a number of startups that could have made sense, didn’t anymore. A new set of entrepreneurs seized on the new smartphones and their app development platforms to make disruptive innovations, with Uber being one of the most successful.

But there’s a lot the entrepreneurs, corporate innovators and investors can and should do before placing a bet on a new product or service, particularly digital ones.

The starting point is identifying dependencies on other products and services. These could be inputs that you need to provide the product or service to customers, complementary products that customers will need to have to make your innovation valuable to them, or customer behaviors that need to be acquired to a substantial degree for your innovation to succeed.

When it started, Netflix needed the DVD format to make its mail model work, but it also needed a reliable and reasonably priced postal service, and customers used to viewing videos at home.

Then, the question is whether, when, and to what degree markets will cooperate to provide fertile ground. In some cases, the dependency is where at or close to where it needs to be — the DVD player has launched, and people love it.

In other cases, it is enough that technologies have been developed and investments made to provide confidence that conditions will be fertile or soon after launch. Netflix could have started thinking seriously about launching a streaming service by the mid-2000s.

Investments in one of the most important innovations of modern times were based on looking at what was in motion. In the early 2000s, it was clear that most people would get mobile phones. The adoption rate was high, and the devices were obviously valuable to people. As importantly, it was easy to forecast that people would have access to very fast, capacious mobile broadband.

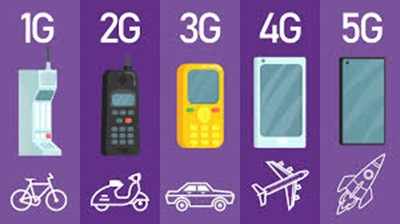

The standard development organizations responsible for developing the next generation of mobile phones (2G, 3G, etc.) outline the goals about a decade before launch. Along the way, it becomes well-known what the speed, latency and other features of the next mobile phone network would be. It is also reasonably predictable that mobile carriers will build faster networks not too long after the development work is finalized.

Apple, Google, Microsoft and others knew in the early 2000s that most people would soon have access to 3G cell networks and that by the early 2010s, mobile carriers would likely roll out 4G networks. Then, people could have a fast, capacious computer in their hands anywhere and anytime.

Do You Have Enough Time?

There’s another important dimension of time that startups and large firms need to consider when they launch what they believe is an innovative product.

Instant successes are rare. It usually takes time for new technologies to get to the point where they can be broadly adopted or for enough customers to embrace them to provide critical mass for profitable ignition and growth.

During that time, others are likely to be chasing the same dream based on similar or different foundational technologies and dependencies. I explored this issue in my article, Can Crytpo Fix Itself in Time? I pointed out that public blockchains, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, have a lot of technological and governance problems that need to be fixed for them to provide fast, scalable and robust networks for payments or other transactions. It would take time to do that. Or for better blockchains to get critical mass to provide alternatives. But the world isn’t standing still— lots of other players, including FinTechs and firms relying on private blockchains, are pursuing some of the same dreams without the same baggage.

Timing Isn’t Everything

Timing, of course, is important, but it isn’t everything. Getting the timing right is often a necessary condition for success. But then it is about having a great product, the right prices, a sound ignition strategy and a solid execution. A bit of luck doesn’t hurt either.

David S. Evans is an economist who has published several books and many articles on the technology businesses, including digital and multisided platforms, including the award-winning Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. He is currently the Global Leader for Digital Economy and Platform Markets at Berkeley Research Group. For more details on him, go to davidsevans.org.