MPD CEO Karen Webster says that everything that you’ve heard over the last several years about how successful mobile payments are at the physical point of sale is wrong. Starting with how it’s taken off like a rocket ship in Europe and how the U.S. is positively pre-historic when it comes to doing anything productive in that department. What’s more, she says that if you’ve used any of these data to support your business decisions, it’s probably cost you a pretty chunk of change without much in the way of a return. The data – the undistorted version – is all right here.

[vc_row full_width=”” parallax=”” parallax_image=””][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Today, I’m going to tell you how billions of dollars could be going up in smoke in the payments business because many of you are making assumptions based on data that is just flat out wrong.

Happy Monday.

But first let’s talk about jobs. (Stick with me, there’s a point here, I promise.)

It’s 2011.

Harvard University Professor Gary King and several of his colleagues launched a project to see if it was possible to monitor chatter on social networks – Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn – and predict shifts in the economy more accurately than conventional models did. A big part of that project was keeping close tabs on how often key words like “jobs” and “unemployment” were used in those social conversations.

At the start of 2011, the U.S. unemployment rate was 9.20 percent and was slowly but steadily inching downwards month by month. By the start of the summer, it stood at 9 percent.

In October, King and his team began to see off the charts chatter on social media related to their observable key words – so much so that they were convinced they were on the verge of predicting a huge reversal of that downward trend well before anyone else even noticed.

Until they realized much later that the spike was entirely attributed to the death of Steve “Jobs” on October 5, 2011.

King speaks openly about his team’s failure at first to distinguish the employment “jobs” from the Apple chief “Jobs” as an unfortunate consequence of relying on what he calls “distorted data.” Luckily for him and his team, the error was caught before their “predictions” were circulated and decisions using data which was not properly vetted were made by everyone from employers to retailers to consumer goods manufacturers.

Which brings me to the subject of mobile payments.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”THE U.S. IS FAR BEHIND THE WORLD WHEN IT COMES TO MOBILE PAYMENTS, RIGHT?” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Oswald%3A300%2Cregular%2C700″][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_center”][vc_column_text]

Take a look at this chart.

It’s just one of several data points that has perpetuated the ongoing narrative about how positively backwards the U.S. is when it comes to embracing mobile payments, and in particular using mobile phones to pay for things at the retail point of sale. That conversation has been in full swing for at least five years, maybe longer. This particular chart shows the U.S. below the global average and totally bringing up the rear when comparing its use of mobile payments in-store to countries a fraction of its size and economic prowess.

Adding to insult to injury, if you’re a member of the U.S. payments and technology sector anyway, is the never-ending stream of reporting about how mobile payments at the point of sale has “taken off” in the U.K., is surging in Korea and about ready to massively explode in China.

Which of course leads everyone, everywhere to two logical assumptions….

1. That the U.S. is not only late to the mobile payments party, everyone else is practically minting money because of the massive mobile payments opportunity at the retail point of sale; and

2. To both save face and catch up, the U.S. payments and technology innovators better make up for that lost time by throwing money at contactless mobile payments at the retail point of sale initiatives – and they better do it fast.

And business decisions are based on those assumptions.

Over the years, there’ve been massive investments in contactless mobile payments schemes by nearly all of the major players across the payments and technology arenas. North of a billion dollars was invested by dozens and maybe even hundreds of innovators and investors – all in response to the loud and growing drumbeat that everyone but the U.S. is cashing in big time on the mobile- payments-at-the-point-of-sale gold rush.

A narrative that’s been helped by “distorted data” that’s just as bad as mixing up jobs and Jobs.

Almost everything you keep reading about the “success” of mobile payments at the retail point of sale is wrong, despite the continued reporting by journalists and analysts that it is.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”THE TRUTH, THE WHOLE TRUTH AND NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH ABOUT MOBILE PAYMENTS SUCCESSES” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Oswald%3A300%2Cregular%2C700″][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_center” style=”” border_width=”” el_width=””][vc_column_text]

Let’s take the U.K.

The U.K. Cards Association keeps impeccable data on payments – volume, usage, transactions, spending volumes – you name it, they track it with precision and have for years. Their 2015 report (which reports 2014 data) says that the total value of transactions using contactless at the point of sale – cards and mobile phones – increased 331% from the year prior.

Wowee!

That’s, of course, the headline that got reported. Everywhere.

And, it is true that contactless volume is growing in the U.K. But it’s sort of like the fact that my Scottish Terrier grew 300 percent in his first 2 months of life. The little guy was still, well, pretty little despite his growth spurt – and still is years later.

In 2014, total card transactions in the U.K., they report, totaled £600B on some 13B transactions.

Contactless volume – cards and mobile phones – was £2.3B of that £600B and 319M of those 13B transactions.

I’ll do the math for you. That’s .4 percent of card volume and 2.5 percent of transactions.

What’s fueled that “massive” increase in volume?

It wasn’t smartphone-toting fashionistas shopping at Harrods.

The average transaction value on those contactless purchases was £6.37 – which is a little less than $10. That’s lunch at Eat, a favorite London lunch spot. The real thanks goes to the London Transport, which in December 2014 alone, drove 11 percent of the contactless volume. And that volume wasn’t the result of using mobile phones, either. Although more than 60 percent of U.K. adults have smartphones, according to Deloitte, the percentage of those with “NFC-enabled SIM cards and phones” is very low. Monthly mobile phone usage at any point of sale is reported to be less than 0.5 percent of the 450 million-500 million NFC-phone owners as of mid-2014, the last time data was available.

Then, there’s Korea.

South Korea has been heralded as one of the world’s most advanced mobile payments’ meccas since about 2010. Google “mobile phone payments in Korea” and you’ll find article after article after article extolling the virtues of South Korean consumers using contactless mobile payments at the retail point of sale there.

Except that’s not the way it really is.

The reality is that mobile payments at the retail point of sale are sputtering in South Korea. According to the GSMA, only 6 percent of terminals there are enabled for contactless payments –mobile or otherwise. Back in 2010 when the mobile payments hoopla started, there was a big arm wrestle over standards that slowed things down. It took Korea Telecom almost two years to get 100k users on board with a QR code based scheme at a handful of merchants. Volume was miniscule and if mobile phones were used in stores, it was to access them for coupons, not make payments, which are still dominated by the use of plastic cards.

Things are starting to turn the corner a little, but only recently.

Last summer, Samsung Pay reported that they had acquired 500k users in the space of a month and racking up millions in transaction volume. Leveraging both existing card accounts and merchant terminals created a ubiquitous payments environment that has expanded the possibilities for merchants, banks and consumers and perhaps broken the mobile payments at the retail point of sale logjam.

The birthplace of NTT DoCoMo and the mobile contactless scheme that inspired just about every mobile payments strategy in the early 2000s.

It’s pretty much the same story.

Sure, there are 70 million NFC-enabled phones in a country of 123.7 million people. But how they’re used is pretty much a carbon copy of how they are used in the U.K. – to buy transit tickets, items from vending machines and snacks at the convenience stores in the train stations.

Even in Australia, everyone’s favorite poster child for the adoption of contactless payments, contactless terminal penetration is still at only 40 percent. And a lot of the contactless activity that’s happening in stores is via cards – not mobile phones.

And does anyone really believe that mobile contactless payments are exploding in China? Not only is there a lack of contactless terminals, there’s a general lack of cards. No cards and no terminals makes for a tough contactless mobile payments environment at the retail point of sale no matter how you try to cut the mobile payments pie.

Now none of this is intended to throw cold water on any progress that is made. All forward progress is great. But the real progress and the rhetoric and hype describing it, you gotta admit, are greatly mismatched.

But there are some mobile payments successes in the most surprising of places.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”TO GO WHERE NO DISTORTED DATA HAS GONE BEFORE” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Oswald%3A300%2Cregular%2C700″][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_center” style=”” border_width=”” el_width=””][vc_column_text]

Where there’s been mobile payments traction, there’s been a real problem to solve – problems that don’t always fit neatly into the existing “everything, everywhere is taking off like a rocket ship” narrative.

One of the most successful mobile payments schemes – and the most successful in terms of penetration in a country – is M-Pesa.

Eight years since its launch in 2007 in Kenya, it’s now used regularly by nearly three-quarters of its population –and 43 percent of the country’s GDP flows through the M-Pesa mobile money network. M-Pesa has also raised the level of economic prosperity in the country significantly, boosting the ranks of the emerging middle class from 20 percent of the population in 2007 to more than 72 percent by 2011. Now that a critical mass of users is established, M-Pesa is starting to expand into payments at the physical retail point of sale.

Schemes like M-Pesa in Kenya, Nettcash in Zimbabwe, and bKash in Bangladesh are not only emerging – but flourishing. It’s not hard to understand why.

In developing economies, mobile payments solve an enormous pain point – how to move money between people in the country without being robbed, killed, kidnapped or having to take two days off work to deliver it. The habit that consumers needed to change was easy-peasy because the alternatives were, well, let’s just say that friction-filled is an understatement. It wasn’t the struggle of finding a card in a bottomless Gucci handbag. It was getting killed on the long journey across rugged, violent territory. And, no, I’m not talking about the drive from San Francisco to San Jose, as inconvenient as that can be these days.

In the developed world, it took a coffee purveyor’s quest to overcome one of its customer’s key frictions to grow the most successful in-store mobile payments scheme. That, of course, is Starbucks.

Oh, wait, aren’t they from the backwards U.S.?

In the space of six years, the Starbucks mobile app accounts for 20 percent of its total volume – some 7 million transactions a week. This barcode-enabled payments-plus loyalty scheme was originally conceived to get customers with gift cards to use all of the balances on those cards. Their hypothesis was that customers didn’t want to be embarrassed at the register by presenting a gift card that didn’t have enough money on it to pay for their purchase – so they never used them fully. The team at Starbucks initially set out to create a mobile app that provided only gift card balance information so that users could avoid that potential embarrassment yet still use the cards.

But when the product managers observed that every single person in line at Starbucks was staring at their phones while waiting in line, they decided to add payments. Starbucks overcame one of its own points of friction by tapping into existing customer behavior – consumers staring at their phones while waiting in line. Being able to avoid public humiliation at checkout with impatient caffeine-deprived people standing behind them, is a huge incentive if using Starbucks gift cards is a consumer’s passion.

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”WHAT YOU MISS IF YOU ONLY LOOK AT DISTORTED DATA

” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Oswald%3A300%2Cregular%2C700″][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_center” style=”” border_width=”” el_width=””][vc_column_text]

Today, and just about everywhere, if you’re brave enough to look past the distorted data, with a few exceptions, the introduction of mobile payments at the retail point of sale introduces more frictions than it solves. Most people chalk that up to inconsistent acceptance of mobile payments apps or restrictions on how much can be spent when using them. And so if we only installed more terminals or raised spending limits, all would be right with the mobile payments world – so let’s get busy doing that now and keep the distorted data stories alive and kicking.

Maybe not.

Think for a minute about the customer experience at Starbucks or riding public transit where it’s a fact that a lot of mobile payments apps are used.

Now think about shopping at a grocery store or a department store or the hardware store.

At Starbucks or at the subway station, a consumer is standing in line or approaching the turnstile holding nothing but her phone, as she waits for someone to take her order or board her train. In just about every other retail situation, she’s pushing a shopping cart filled with stuff that she has to unload and stick on a counter or a conveyor belt (and maybe even has to put in bags), or is holding a bunch of stuff in her arms while standing in line (maybe even while holding her kid, too).

Her phone is with her but probably not in her hand.

So, when she gets to the checkout counter, absent a really good reason to reach for her phone in her purse or her pocket and/or with the knowledge that if she does, the method of payment she has on her phone will be accepted everywhere she shops, she’ll just default to reaching for her leather wallet and her plastic card that she knows will.

That’s exactly what the Apple Pay experience has shown, too.

Even the most enthusiastic early adopters are no longer reaching for their phones to pay in the stores. If they still have to stand in line with stuff in their hands or in their carts that they have to unload, and reach for anything when it comes time to pay, it’s a whole lot more natural to reach for their plastic card and not the mobile payments app – all things equal.

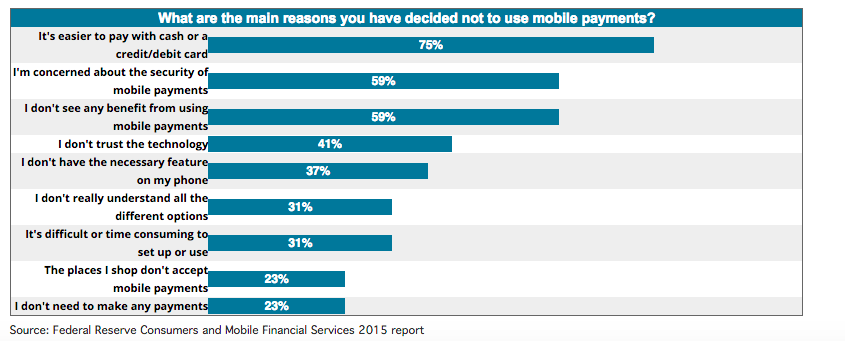

Based on what consumers have said, when asked, even adding loyalty options might not be enough to get them to switch. According to the latest Fed’s Survey of Consumers and Mobile Financial Services, it’s just easier to use cards and the vast majority – some 65 percent – say that nothing can get them to change their minds.

Unless of course, someone does something to remove the friction from checking out in the store.

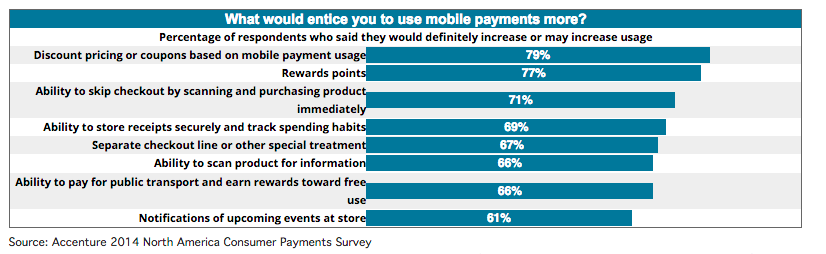

A 2014 study by Accenture shows that, short of actually paying people to use a mobile payments app at checkout, what would get nearly three quarters of them to take mobile payments for a spin is the ability to skip the line completely.

And it makes total sense.

All of the data show that making checkout easier on the mobile phone increases conversions.

So, why wouldn’t the same principle hold true in the physical retail store?

And inspire innovators to use the mobile device and apps to reinvent the in-store shopping and checkout experience?

Which is why the order online and pick up in-store innovations across all categories of merchants are growing like gangbusters. What better way to skip the line than never getting in one?

[/vc_column_text][vc_custom_heading text=”DON’T HATE ME BECAUSE I’M NOT DISTORTED” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Oswald%3A300%2Cregular%2C700″][vc_separator color=”black” align=”align_center” style=”” border_width=”” el_width=””][vc_column_text]

None of what I’ve written is intended to take a swipe (no pun intended) at the potential for mobile payments at the retail point of sale but to, instead, provide a much-needed reality check on where things stand right now (and actually have for a while). For those of you who haven’t been following me, I’ve been touting the advantages of moving to mobile at the point of sale for about a decade now—but also emphasizing that it won’t get anywhere unless it solves big friction – and a real friction – at the point of sale.

The reality check is that there are mobile payments success stories but just not as many at the retail point of sale as the “distorted data” accounts might have you believe.

And, most important of all, no one anywhere in the world has missed out on a massive in-store mobile payments opportunity. In fact, it’s all really just getting started.

Those that are showing signs of success share a common characteristic that the distorted data stories ignore but you shouldn’t. Innovators have looked beyond the obvious to understand how to make things better for the consumer and the retailer – instead of what we’d like them to adopt because we happen to know how to make it work.

[bctt tweet=”Innovators have looked beyond the obvious to understand how to make things better for the consumer…”]

For those who are thinking that way, take great comfort in the fact that you’re not missing out on a thing. And, with any luck, you’ll have some great undistorted data to share on how you’re doing soon enough.

Be sure to write to me when you do. We’ll tell the whole world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]