The Rumble In Big Retail’s Jungle

The world lost “The Greatest of All Time,” boxer Muhammad Ali, over the weekend due to complications associated with his 32-year battle with Parkinson’s disease. Ali lived up to his famous self-appointed moniker in many ways – for his civil rights advocacy, his worldwide charitable and humanitarian efforts and, of course, his prowess as one of the greatest boxing champions of all time.

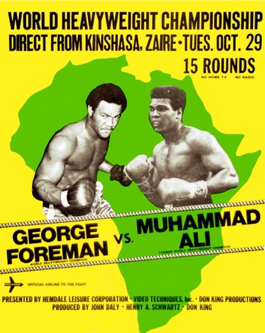

Perhaps one of the greatest – and most historic — of those bouts was the 1974 matchup between Ali and then world heavyweight champ George Foreman. Sports enthusiasts say that the Rumble In The Jungle, as it was billed, goes down in history as not only the most famous boxing match of all time, but the greatest sporting event of the 20th century.

For those of you who weren’t even alive in 1974, this match was a pretty big deal for Ali for a couple of reasons.

For those of you who weren’t even alive in 1974, this match was a pretty big deal for Ali for a couple of reasons.

Ali was stripped of his heavyweight boxing title in 1967 for nearly four years after he refused to honor the draft, join the Army and fight in the Vietnam War. In 1970, Ali got a license to fight again to regain the title he lost and took on then titleholder, Joe Frazier.

He lost.

Ali was faced with the harsh reality of having to fight his way back up the championship ladder.

Advertisement: Scroll to Continue

The Rumble In The Jungle was promoted as Ali’s big comeback after a pretty lackluster performance since he got his license back. It had all of the ingredients of a first-rate media spectacle: 60k in attendance, a global television audience and three days of buildup with concerts and other celebrity-studded festivities.

At the time, Foreman was lauded as the greatest and most powerful puncher ever to have taken to the center ring – and considered the hands on (ha ha) favorite given the brute force behind his powerful “haymakers.”

Ali, on the other hand, was perfecting a different tactic.

His “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” approach was a combination of deft footwork, and technical maneuvers intended to catch his opponents off guard and wear them down before going in for the finishing blow.

One of those tactics, the “rope-a-dope,” delivered the finishing blow to Foreman, quite literally, in the eighth round. After employing a number of moves earlier in the fight to disorient Foreman and force him to waste his power on punches that missed their mark, Ali lured Foreman into attacking him against the ropes so as to tire him out. It was then that Ali went on the offensive and punched back strong, scoring the knockout punch to reclaim his title. (And – little known fact: launch Don King’s career; this was his first fight promotion.)

The Rumble In The Jungle was an epic rivalry between two powerful players.

A powerful incumbent champion who was strong and dominant for years.

Success and longevity for Foreman was a function of relying on what had always worked for him: strong punches that simply pummeled challengers and knocked them into oblivion. Challengers who trained so that they could deliver strong powerful punches were simply no match at beating the champion at a game that he simply owned.

A nimble challenger with a new game plan.

Ali knew he had to deliver a knockout punch in the end to win, but needed new techniques on the way there. Ali knew he couldn’t match Foreman punch for punch, so he decided to take the fight to a new playing field: the ropes, instead of the center of the ring. Once on turf that Ali knew better, he could use new techniques to both disorient and then wear the champion down and, at that point, lure him to the center of the ring and deliver the finishing blow to a champ that never saw it coming.

The Rumble In The Big Retail Jungle

Last week, the biggest retailer in the world by revenue, Walmart, made an announcement that made it clear that it’s really not that interested in ceding the title of world’s biggest retailer to a younger, and nimble challenger named Amazon.

This, of course, is Walmart’s announcement of a new partnership with Uber and Lyft to leverage those ride-sharing platforms to deliver groceries in a two-hour window to Walmart customers. Walmart has been trialing this in a couple of markets with Deliv, and is now ready to expand its efforts on a national basis with partners that have a density of drivers to serve its hundred million consumers.

Walmart is already one of the biggest grocery stores in the country, accounting for 25 percent of all grocery sales; that’s up from 7 percent in 2002. Under this new arrangement, payment is made via the Walmart.com app after customers make their selection online. Walmart employees do the shopping, load the Uber/Lyft car with said bags and then make the delivery. A delivery scheduled for two days post-order gets delivered at a cheaper price.

It’s a pretty brilliant stroke, I think for Uber (and Lyft) and Walmart.

Walmart gets the benefit of a ready-made pool of drivers with critical mass in the areas that they need to serve. I don’t know the details of the partnership, but certainly some of the costs are only incurred when service is performed. This keeps Walmart’s economics in check – why build when you can rent the services of a complementary platform when needed?

For Uber and Lyft, this is pure profit to the bottom line that keeps drivers happy by giving them more work. Uber drivers complain in some cities that there is too much supply and not enough demand. Uber just created more demand – just like they have with UberEats, which also leverages Uber drivers for pickup and delivery.

Walmart’s announcement comes on the heels of a number of other digital and in-store initiatives that it has launched over the last year.

An in-store system alerts Walmart associates when customers come into the store to pick up things ordered online. Shipping Pass allows consumers to pay $49 a year to have orders delivered in two days – no minimum purchase required. Walmart Pay is a mobile app that uses the Walmart.com app to enable in-store payment using any phone, and leveraging the user behavior of the 22 million consumers a month who comScore says visit the Walmart physical store and use their Walmart.com app while there to check prices, etc. Walmart Pay consolidates all relevant Walmart promotions, Savings Catcher balances, unused gift cards (among other things) and applies them at checkout.

This announcement also follows a very strong earnings report which even took a few analysts by surprise. It reflected five quarters of upward revenue growth and increased foot traffic – a big challenge for most physical retailers today. These results are driven partially by buy online pickup in-store initiatives that not only has consumers coming into the store, but according to CEO Doug McMillon, when that behavior is applied to grocery orders, sees consumers spending 50 percent more when they get there.

And don’t forget that Walmart.com and now Walmart Pay allows consumers to buy online and pay in cash at the store for what they order online.

Walmart’s stated mission is about making people’s lives better by helping them save money. Sam Walton once said that there’s only one boss – the customer – who can fire anyone in the company by simply spending her money somewhere else.

According to a survey done by Kantar of 4,000 consumers, that boss skews toward those who make $50k or less. Saving money is, therefore, mission critical to Walmart shoppers – and is their No. 1 priority.

Walmart delivers on that mission by operating a pretty sophisticated supply chain and distribution network that includes its 4,000+ physical store footprint stores which are within a 15-minute ride of 90 percent of all people living in the U.S. In addition, Walmart’s 150+ distribution centers are strategically situated within 150 miles of a Walmart store. Walmart also operates a company-owned fleet of ~70k tractor/trailers and 7,800 drivers who deliver daily to those locations.

Walmart delivers on that mission by operating a pretty sophisticated supply chain and distribution network that includes its 4,000+ physical store footprint stores which are within a 15-minute ride of 90 percent of all people living in the U.S. In addition, Walmart’s 150+ distribution centers are strategically situated within 150 miles of a Walmart store. Walmart also operates a company-owned fleet of ~70k tractor/trailers and 7,800 drivers who deliver daily to those locations.

A Retailer On The Ropes?

Walmart’s revenues of nearly half a trillion dollars ($485 billion in 2015) and 2.2 million employees – half of which are in the U.S. – makes it the largest retailer in the world in terms of revenue and number of employees. One hundred million people step foot in a Walmart store every week and $36 million dollars are spent in a Walmart store every hour. We estimate that eight cents of every dollar in the U.S. is spent at a Walmart.

There’s no doubt about it, Walmart is a big and powerful incumbent that’s historically delivered knockout punches to a host of challengers over the years. It’s controversially driven many mom-and-pop shops in local communities out of business. Its annual revenues are nearly 7X that of its closest rival, Target. Its formats have evolved to serve a variety of customer needs, including membership clubs like Sam’s Club and smaller format stores that hope to attract a new type of customer in a more urban location.

So why then do so many think that Walmart is on the ropes?

Well, here are two reasons. One could be worth breaking out the worry beads and one might not be.

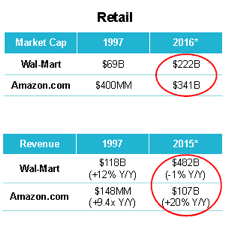

The first is from Mary Meeker’s hot-off-the presses 2016 Internet Trends report. This chart shows that while Walmart may have 4x the revenues of Amazon, the market seems to be betting that it’s the younger, more nimble challenger who’s best prepared to capitalize on the digital waves that are transforming retail and commerce more broadly.

How much of a worry depends on how much of that market cap reflects the value of non-retail efforts such as Amazon Web Services, its content production and streaming business.

Amazon reports a 17 percent margin on the service and an annual growth rate of 49 percent and is said to own roughly 30 percent of the cloud infrastructure market. Some analysts have ascribed a ~50 billion valuation on the service in 2015. Backing out that non-retail dimension of the business closes the market cap gap a bit.

But where the worry beads might need to come back out of the drawer is because of this next chart, which shows that the customer base that Walmart has locked and loaded today isn’t that digital millennial native shopper who needs to be the Walmart customer tomorrow.

It’s why when Walmart’s eCommerce numbers dipped last earnings report, growing at only 10 percent, the headlines didn’t tout how well it did in the physical channel, it slammed them for whiffing online. And whiffing after saying that they have sunk $1.5 billion into eCommerce efforts that, analysts said, have not borne much fruit to date.

In What Jungle Will We Rumble?

Amazon, over the last 20 years of its life, has taken the retail fight to a different part of the ring: online and mobile.

It started life as a digital retailer, selling things that appealed to all people: books. And in an environment that was unencumbered by the physical real estate that has become an albatross to many of its brick-and-mortar challengers.

We all know the rest of the story. Those book sales turned into a massive online store selling just about everything, and now everything delivered in two days (and even sooner) to Prime customers.

Amazon is a massive online marketplace with more than 480 million products listed on its U.S. website – and is said to add 485,000 new items each day. Fifty percent of those items are from marketplace sellers, and the rest from Amazon’s traditional buy wholesale/sell retail business.

Amazon has cultivated three secret weapons in its quest to change the retail playing field. Its Prime customer base of which there is said to be ~54 million, who are not only brand loyal, but big spenders – outspending non-Prime customers by a factor of two to one. Amazon uses data on what its 304 million customers buy in order to personalize the shopping experience in a helpful, and not intrusive way. And they leverage the trust of its customers so that they buy even more things and, they hope, help it become the trusted digital credential that consumers take everywhere they go digitally to conduct commerce.

Amazon today accounts for 20 percent of online retail. One of comScore’s senior executives told CNBC in November of 2015 that Amazon’s share online is “higher than the next six retailers combined,” and that “there no evidence that things are slowing down for them.”

Like Walmart, Amazon is pouring gobs of money into logistics and distribution. Its deal with the U.S. Post Office enables cost-effective delivery using someone else’s critical mass and capacity. Amazon’s also bought a slew of tractor trailers to control its own delivery future and is investing in distribution centers like there’s no tomorrow. Then there are the planes that it’s leasing, the German airport it’s rumored to be buying and the drones that it would like to see added to its delivery repertoire.

And, just like Walmart, Amazon’s also left a lot of causalities in its wake.

Physical bookstores are a mere shadow of themselves – if you can even find one. Most big box retailers are taking their lumps either directly or indirectly thanks to Amazon. As Jeff Bezos famously said, “your margin in my gain,” and that retail margin turned Amazon gain comes in the form of either lost sales or lost margin as the consumer’s expectation of delivery from those stores has now become two days or less – or someone else (like Amazon).

Get Ready To Ruuuuuuuumble!

In one corner we have Amazon – that nimble challenger to retail that is today, a big fish in a small retail pond called online sales.

Census says that online sales are roughly 8 percent of all retail sales, Mary Meeker says it’s 10 percent after backing autos and a few other things out. In either case, Amazon owns 20 percent of that 8 or 10 percent that’s online sales today.

1.6-2% of all retail sales doesn’t evoke images of either Ali or Foreman.

But, Amazon is skating to where the puck, and its mobile-toting, Alexa-passionate and Amazon-loving customers are going, and investing in even more things that will drive the commerce experience online in some way. Presumably that’s why analysts perceive the long-term value of Amazon to trump Walmart.

Amazon’s vision of the retail world has digital retail capturing more and more of the retail flag than its brick-and-mortar incumbents have today. It’s investing in delivering that future — plowing billions into experiments that will get them there first and fastest, delivering the convenience of buying online and getting things delivered fast at the same time they keep prices low, leveraging their assets and customer base along the way.

Amazon’s strategy is designed to keep its other online and physical retail challengers punching and punching and punching as it bobs and weaves, building out their digital assets and expanding their digital ecosystem. Then going in for the knockout blow when they believe that their physical retail competitors are most vulnerable after years of fighting back but losing ground during each round.

In the other corner we have the Walmart – the reigning heavyweight champion of the world in the big pond called physical retail – where 90 (or 92 depending on what source you believe) percent of physical retail still happens.

Its knockout punch over the years has been everyday low prices and physical distribution that makes it convenient for consumers to visit a store since 90 percent of consumers live within 15 minutes of one. And in key sectors, like groceries – the one thing that everyone needs to buy – it has a commanding share, allows consumers to place orders online and pay for those orders in cash if they want to, and has a massive business from consumers who use food stamps to buy their food. Four percent of Amazon’s grocery business is from people using food stamps to make grocery purchases.

Amazon’s share of grocery sales is reported to be .8 percent.

But the physical retail pond in which Walmart has been so dominant now has a powerful undercurrent called digital retail – and Amazon.

Consumers visit fewer stores – and less frequently. When they visit those stores, they go to buy, but the discovery part of their journey has happened well before they step foot in those stores. The consumer only goes to Walmart or any physical store if they have something that a consumer can’t or doesn’t want to easily buy somewhere else, including on Amazon.

Physical store convenience still matters, but only when consumers feel that the trip will be worthwhile.

And The Winner Is …

Who wins the rumble in the jungle remains to be seen and, as all of these things go, will be decided by the consumer who’ll ultimately deliver the knockout punch.

For physical retail, that fight will be fought – and won — well before she ever gets to your physical front door.

That means that every single physical retailer better think about their business in the very same way that Jeff Bezos does: “We don’t make money when we sell things. We make money when we help customers make purchase decisions.”

Where those purchase decisions actually get bought – and from whom — will be the rumble in the big retail jungle that every retailer should now be training for.

It made me wonder whether the Walmart/Uber-Lyft partnership announcement is part of Walmart’s training to rope-a-dope their digital challenger, Amazon.

Maybe Walmart is using its low prices, and massive delivery and distribution network to both juice its Walmart.com numbers and Walmart Pay user base, and hook more consumers into going to Walmart more often. Doesn’t sound implausible to me.

Consumers don’t buy all of their groceries online, but having them locked into Walmart for that one ubiquitous product category that every single person needs to buy (sound familiar?) could be a big first step into getting existing consumers to buy more — and for new consumers to give it a try.

Walmart is also leveraging a platform strategy that delivers reasonable economics for them and uses brands like Uber and Lyft that the digital natives they want to court also use and associate with hip and happening digital commerce innovation.

Could groceries be to Walmart what books were to Amazon – a product category that everyone needs to buy and Walmart can deliver cheaply and conveniently to get new consumers hooked?

Getting new consumers into the mix is mission critical for Walmart. So is plowing even more of its investments into product innovation and taking a good look at how its physical footprint needs to evolve to deliver the “omnicommerce” promise that these digital-savvy consumers demand.

Amazon, on the other hand, must be prepared to float like a butterfly and sting like a bee across the categories of physical retail that consumers want to buy online and in which the experience of doing so is better than what consumers can get from its physical retail counterparts.

If price and convenience are now table stakes, the experience must win the day.

Twenty years after the Rumble in the Jungle matchup, a 45-year-old George Foreman regained his heavyweight championship title by knocking out a 27-year-old challenger. Foreman’s lifetime record of 76 wins and 5 losses includes 68 knockouts and the distinction of being the oldest heavyweight champion in history.

Ali’s overall record was 56 wins and 5 losses and 37 knockouts.

One knockout punch, it seems, doesn’t always mean that the fight has been lost forever – regardless of who threw it and when.