That’s a real 180 from the drubbing analysts have mostly given Uber ever since it went public in May of 2019.

Each earnings report since then has raised the inevitable questions about Uber’s massive losses and its seeming inability to keep its core business strong and competitive with its ride-hailing counterpart, Lyft, now a decade after its launch.

Lyft, you will recall, stormed out of the IPO gate with a vengeance, with a stock price of $72 per share and a market cap of $26 billion. Uber followed a month later with a much more muted showing, trading below its IPO share target and breaking it for the first time in June. Lyft will report its Q4 2019 earnings this week. As of Friday, it was trading at $49.92 a share with a market cap of $14.6 billion, well off its high the day it went public – and unable to get close ever since.

Sound familiar?

It should, since it’s nearly identical to the drubbing Amazon received a decade into its existence as a disruptor seeking to change how people searched for, found and bought stuff.

Advertisement: Scroll to Continue

Taking a Trip Down Amazon’s Memory Lane

It’s easy to forget now, but back in 2004, an almost 10-year-old Amazon was being eviscerated over its massive losses and questioned repeatedly about its ability to compete, online, in selling things that weren’t books, videos or music. “What kind of company can’t make money a decade into its existence?” industry pundits would question. “And why are its investors so patient with this retail money-loser?”

When Amazon reported its earnings in January of 2004 for the Q4 2003 quarter, it posted a profit for the first time, yet its stock took a big hit. Among other things, analysts cited its 35 percent growth in electronics and general merchandise sales as an indication that Amazon’s growth was slowing in those categories in the face of competitive and pricing headwinds. At question was its growing reliance on its marketplace business to drive sales, as well as the uncertainty of how Amazon would manage those prices and margins.

A year later, in 2005, analysts raised even more concerns over Amazon’s continued losses, and the investments needed to support the introduction of a membership program that asked people to pay to $79 a year to guarantee two-day shipping. Besides believing that few people would ever pay that much just to get free shipping, analysts also wondered why in the world Amazon would ever give up so much shipping revenue.

On top of that, analysts flagged well-funded startups such as Overstock.com and SmartBargains.com that were “nibbling away at Amazon’s market share.” At the same time, traditional brick-and-mortar retailers posed a growing threat – at the time, more than 95 percent of retail sales didn’t happen in the channel that Amazon had identified as its competitive advantage. The company’s market share was about $14 billion that year.

I’ll spare you the “what a difference 15 years makes” cliché.

While the rest of the world was trying to compare Amazon – a decade into its life as a company – to Overstock.com and Walmart, Amazon was building a trillion-dollar platform that the rest of the retail world would have to measure up to – and compete with – in due time.

The Retail Platform Sales Slayer

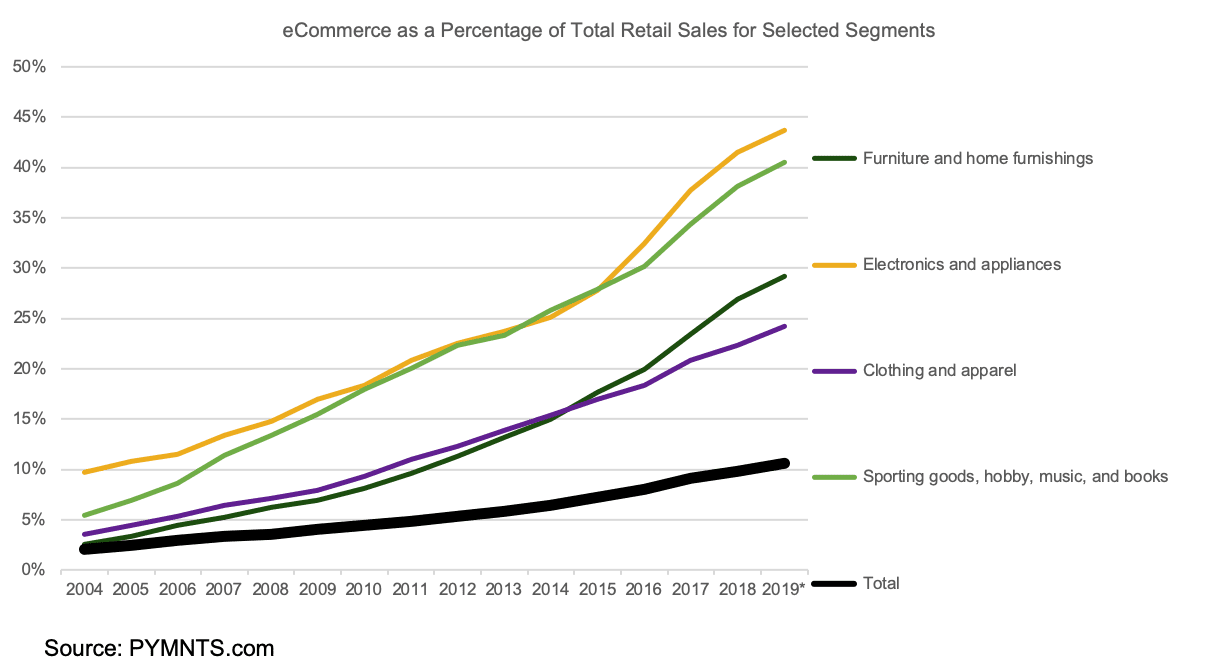

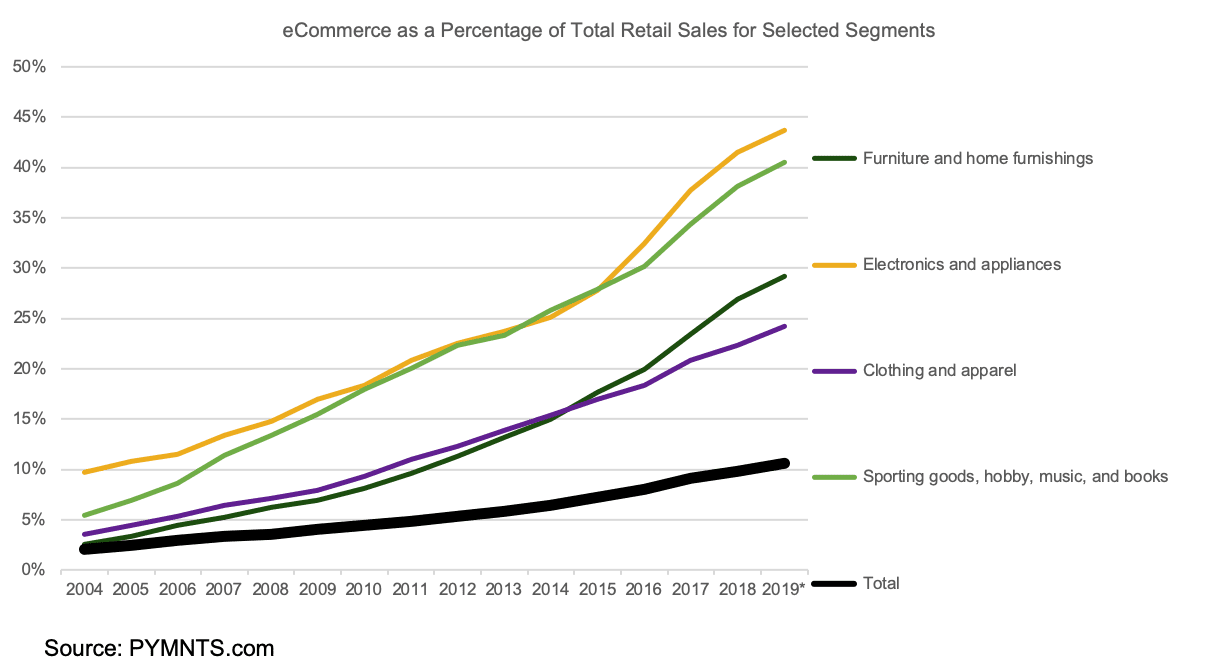

Twenty-five years after Amazon opened its virtual doors and kick-started the idea of buying new merchandise from an online marketplace, our analysis of online spend and share shows that about 44 percent of electronics sales are online, as are 41 percent of sporting goods and hobby sales, and 24 percent of clothing and apparel sales. We estimate that Amazon accounts for between 25 and 30 percent of online sales across each of the electronics, sporting goods and hobby segments, about 10 percent of clothing and apparel sales, and more than half (51 percent) of all eCommerce sales in the United States.

As for those well-funded startups back in 2005 that were poised to eat Amazon’s lunch, today Overstock.com gets about 24 million visitors a month and SmartBargains.com doesn’t get enough to register on the internet tracking site that provides those numbers. That compares to Amazon’s 2.3 to 2.7 billion monthly visitors in the U.S. Three hundred million people pay for the benefits of Amazon Prime –which now go well beyond free two-day shipping.

As for Walmart, we track the overall share of Walmart’s online spend and Amazon’s online spend in the key categories that drive retail spending quarterly, and provide an update on what both companies are doing to hone their retail strategies.

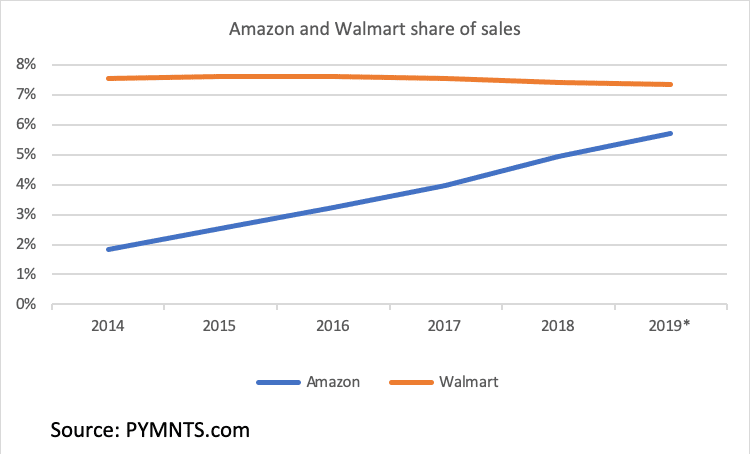

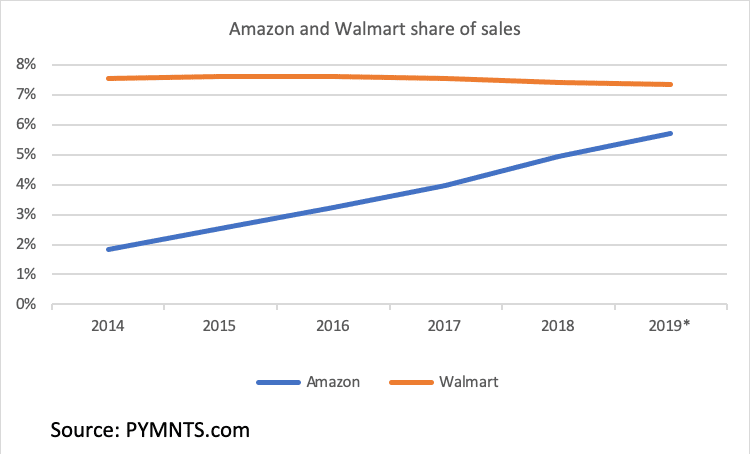

We observe that Walmart’s annual retail sales growth has been about 2.7 percent over the last five years – about the same percentage that total retail sales have grown over that period. Amazon has grown its retail sales about 30 percent (29.6 percent) over that same period – and, we estimate, now accounts for roughly 6 percent of all retail sales, up from 2 percent five years ago. Today, Walmart accounts for more retail dollar sales overall than Amazon, but their share of all retail sales has remained relatively flat, at more or less 8 percent.

In other words, Amazon is closing that gap.

Much of Amazon’s growth in retail has happened in the last five years, as its investments in logistics to support the delivery of its retail strategy, along with its offline retail investments, have destabilized the competition and drawn more of the consumer’s dollars. Amazon used its platform assets to color outside of the traditional retail sales lines, redefining the shopping experience for the consumer and all of the stakeholders who are now part of its ecosystem.

Those earlier fears over Amazon’s inability to grow share beyond books now seem laughable – as does the failure to understand how it was steadily evolving its strategy to ignite and scale its platform.

Just like many seem to underestimate Uber’s power, pigeonholing it as little more than a ride-hailing platform competing for consumers who don’t want to drive their car or take a taxi.

The Platform Playmaker

I wrote a piece last April, shortly after Lyft went public and shortly before Uber did, positing that Uber could become the next trillion-dollar platform. At that time, Uber’s market cap was expected to be around $100 billion. Declaring that Uber could come anywhere close to that valuation seemed nuts. After Uber went public and more earnings were posted, some thought it seemed rather disconnected from reality.

That’s because I believed then, and still do, that in 2009, Uber didn’t just set out to build a better and more predictable version of the taxi.

Like many of the trillion-dollar-market cap players in the platform economy today (Apple, Google, Amazon, Microsoft), Uber is leveraging its platform assets – its critical mass of drivers and consumer users, along with the technology that powers the on-demand Uber experience – to find new sources of value for its platform and the stakeholders who are a part of it.

With Uber Eats, launched in 2012, Uber added a new “side” to its platform – restaurants, which had their own logistics challenges. Today, Uber reports nearly 400,000 restaurants are part of its network, a nearly 15 percent take rate of its 111 million monthly average platform consumers and $4.37 billion in annual revenue, up 71 percent in 2019. Eats is the second-largest restaurant aggregator in the U.S.

Uber Freight was launched in 2017, adding carriers and shippers to its platform by making its billing and tracking tech available to 36,000 carriers and 400,000 drivers across a diverse group of manufacturers. The value proposition is for Uber to bring the same level of transparency and certainty to the freight business that it brought to the consumer ride-hailing business.

In 2018, Uber added healthcare providers to its platform. These providers face a unique set of logistical problems in getting patients to appointments. Uber’s integrations with healthcare providers and their billing platforms help patients more reliably reach doctors’ offices, which reduces wait times and non-adherence.

As Uber has gone global, it has expanded its consumer transportation options – bikes, scooters and whatever is local to the countries and cities in which it operates – as well as acquisitions, partnerships and integrations that provide loyalty and other rewards for using Uber.

Over the years, Uber has also tweaked its business model and added subscriptions for both Rides and Eats. The company reported last week that consumers who use two or more services on the platform have a number of transactions that are now three times that of a single user. Uber has also improved the speed at which it pays its drivers – instantly – and launched Uber Money in 2019 as a “super app” for its drivers to get paid and then pay for the things they want to buy for themselves and their businesses. Deals on gas purchases and other incentives are intended to get Uber drivers to sign up and then, over time, rely on Uber Money as their primary banking relationship.

That Platform Vision Thing

Over the years, Amazon became much more than a new retail channel, even though that is how it started. Today, its connected commerce ecosystem – online and off – gives consumers and retailers more and more ways – and reasons – to live conveniently within it, and players more incentives to become part of it.

For Uber, transportation is a platform feature that’s central to its business, but ride-hailing is not its end game. Today, Uber is a last-mile logistics platform, one that uses its global network of drivers and consumer users – and the technology that powers the on-demand Uber experience – to remove the friction associated with moving people, products and services from point A to point B.

The cars and scooters and bikes and rickshaws and tractor-trailers that Uber drivers operate are nodes on a global last-mile logistics network that gets people where they want and need to go, delivers dinner from a restaurant to a home, gets patients to and from medical appointments and digitizes and delivers freight from a manufacturer to a distributor or store – and who knows what else over the next decade.

The market opportunity for Uber is massive, since solving for the last mile is a huge and expensive problem that everyone serving the consumer in a connected world now faces. Which is just about everyone.

It’s why in the connected economy of the 2020s, logistics will make or break a company’s future.

Last year, Amazon delivered more packages then FedEx did and remains a threat to traditional retail. Sure, it increasingly has more of the stuff that people want to buy, but also uses its logistics expertise to reduce the uncertainty of when people will get what they do buy.

Last year, about three million Uber drivers gave 6.9 billion people rides, up 32 percent from the year before. Uber has just shy of a million drivers in the U.S. For the company, there is enormous value in having driver density in all of the places where consumers and businesses need to connect with each other – and an opportunity for businesses to tap into an efficient, last-mile ecosystem to compete and find new sources of value for their consumers.

The company has been able to build up a dense network of drivers in local areas because it provides a great way for people all over the world to make money, on-demand and at their convenience, to build their own futures. And it provides them with a lot of services, like payment, that makes it a breeze to turn some spare time, and a spare vehicle, into quick money.

That provides the foundation for building lots of businesses – some known now, some as of yet unimagined – that depend on an efficient way to solve last-mile problems. Like Amazon, Uber will start some of those itself, and will capture more and more new categories. And it will serve other companies that will use its solution as a critical input into their business.

Maybe it will stumble. Maybe regulators will throw sand in the gears. But there is certainly the opportunity to create a trillion-dollar-market-cap company, and a vibrant ecosystem, in the next decade or two.