Turns out that not many people order burgers at a restaurant that sells pasta and pizza, even though they’re a menu option. But many did from MrBeast Burger, a delivery-only brand that debuted in December of 2020, made by chefs in an Italian restaurant.

Named after YouTube personality MrBeast, Virtual Dining Concepts licensed the MrBeast Burger recipe to Bertucci’s (and others) as a virtual brand for delivery only. That gave them the chance to recoup dollars lost to COVID shutdowns by monetizing idle chef and kitchen capacity with another product. After less than two years, MrBeast Burger is now available in 1000 restaurant locations, with annual revenues that some have estimated at $32 million. Licensees are said to average $500 in profit a day.

Pasqually’s Pizza & Wings launched as a new delivery-only premium pizza brand on Grubhub in May of 2020. Consumers looking for variety in the midst of the COVID-lockdowns were enticed by its mouth-watering pictures of pizza, spicy wings and garlic bread and gave it a go. It wouldn’t take long before consumers discovered that Pasqually’s was a virtual brand created by Chuck E. Cheese and named after a musician in the Munch Make Believe Band. Chuck E. Cheese chefs prepared pizza and wings in their kitchens using the same sauces and ingredients in foods served in the restaurant. Like Bertucci’s, CEC was able to monetize the idle capacity of their chefs and kitchens during the dark days of COVID. Today, Pasqually’s is available for delivery from more than 400 Chuck E. Cheese locations in the U.S.

There’s another player hiding in plain sight in the restaurant space — a platform operating successfully in the food and food services segment with capabilities that can be leveraged at scale.

Amazon — with Whole Foods, Amazon Fresh, high-spending Prime Members, embedded one-click payments, last-mile logistics capabilities and a fast-growing prepared foods business that uses its own kitchens — is hiding in plain sight, capable of disrupting how and where consumers find, buy, pay for, and eat their food.

And like every other sector in which Amazon has leveraged its platform assets to enter, it could trigger the reinvention of the grocery and restaurant sectors when it does.

Platforms Hiding in Plain Sight

The idea of hiding in plain sight can be traced back to the mid-18th century and the use of camouflage to keep soldiers from being less conspicuous in battle. The French are credited with further commercializing camouflage and the art of military deception in 1915 by giving soldiers uniforms that blended into the scenery of the battlefields. Today, advances in technology offer military strategists new ways to use the element of surprise to their advantage.

The perfect storm of the pandemic, technology and connected devices over the last two years gave many businesses hiding in plain sight a way to disrupt traditional businesses that never saw them coming.

Zoom and Microsoft Teams have disrupted business travel as well as the commercial real estate sector as more businesses now want to reduce or eliminate their office footprints. At the same time that COVID gave employers an opportunity to experience a productive and connected remote workforce in action, business executives and their CFOs were given a cost-effective substitute to hopping on a plane or paying for more office space than they needed.

Ironically, perhaps, the same video conferencing technology that made nary a dent in business travel or office space in the 1980s and 1990s is now cloud-based and accessible to anyone using any connected device — and it’s making a huge dent in their respective universes.

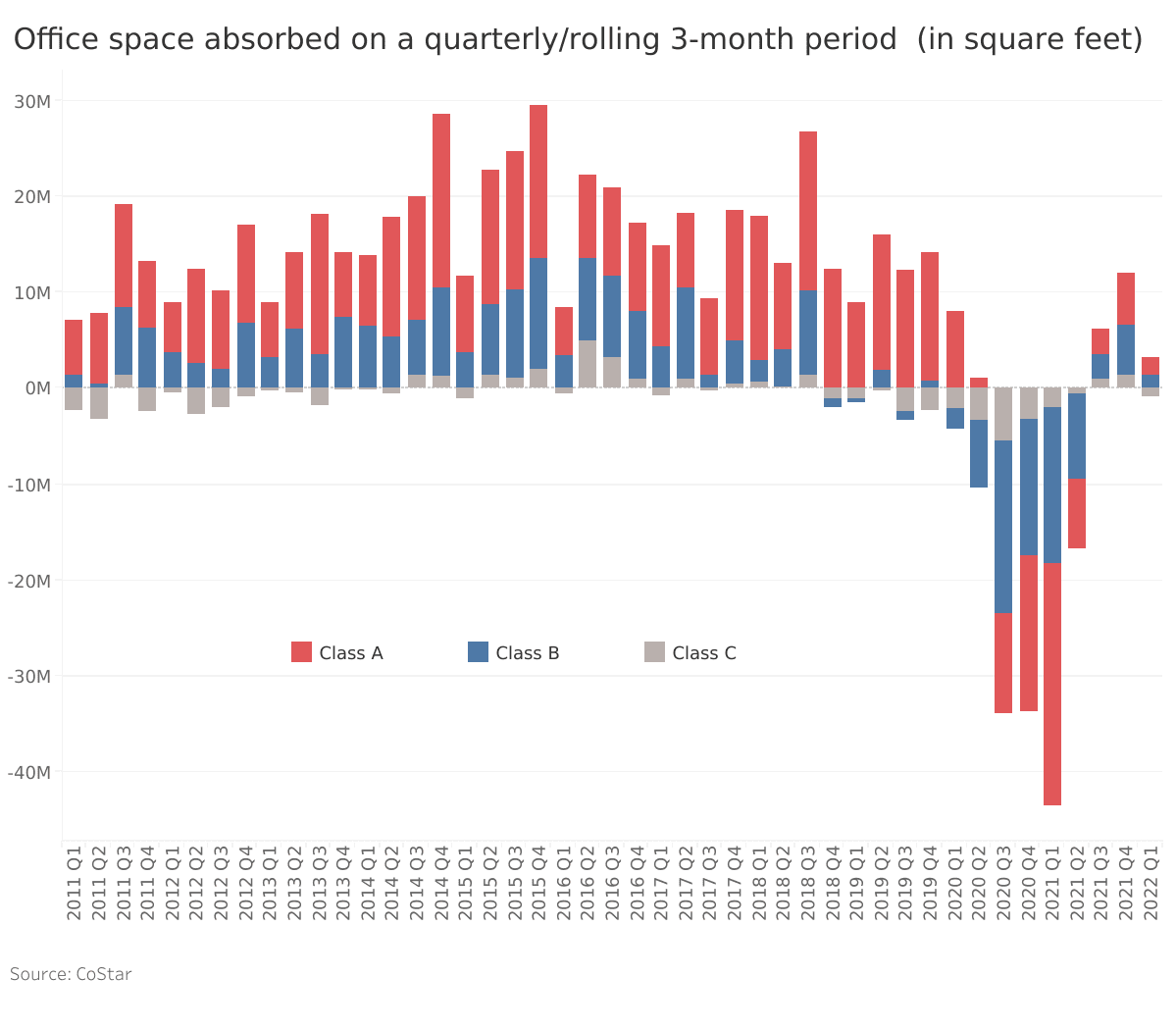

The U.S. Travel Association predicts that it will take until 2024 for business travel to reset to 76% of its 2019 levels; some believe that 2019 was the business travel high-water mark. The National Association of Realtors reports that with 110 million square feet of unoccupied commercial office space in mid-2022, it will take at least 11 quarters for that space to become fully occupied. The current economic headwinds, and ongoing improvements in workforce productivity technology, will further pressure the outlook for both.

Hiding in plain sight is also a strategy that successful platforms use as they expand their reach and create new opportunities to monetize their assets and capabilities.

Uber founder Travis Kalanick described Uber’s mission in 2009 as making it possible for goods and services to be ordered and delivered from the touch of a single button, emphasizing the value of Uber’s drivers to execute that vision. More than going head-to-head with the taxi industry, Uber’s innovation was creating a logistics platform capable of organizing the idle capacity of black car drivers and giving birth to the gig economy as we know it today. The platform was hiding in plain sight, capable of scaling Uber’s business well beyond its core.

At launch, Uber’s first use case was ride-hailing; then came food delivery in 2014 with Uber Eats using the same supply of drivers. Uber’s riders are now customers of that aggregator service that has expanded to include ordering sundries at convenience stores and items at selected retailers. With Uber Explore, those ordering options now include booking tickets to events and reservations at dining establishments as part of providing an integrated travel experience for its users — and more revenue opportunities for its drivers.

Not Amazon’s First Restaurant Rodeo

Amazon launched Amazon Restaurants in Seattle in 2015. It shut it down in June of 2019.

In its heyday, Amazon Restaurants operated in 20 US cities and London. In Baltimore, consumers were offered 59 different restaurants to order from and promised a one-hour delivery window [one hour!], but not a full option of menu choices from those establishments. It was a friction-filled experience for a platform that had built its reputation on choice, eliminating friction when ordering online and fast and reliable delivery.

Competition from food aggregators and the logistical challenges of entering an entirely new on-demand, same-hour delivery business are said to have hastened Amazon Restaurants’ demise. A contributing factor was also said to be the effort on the part of the Amazon management team to fully integrate its 2017 Whole Foods acquisition into the business.

Amazon’s Food Cornerstone

Buying Whole Foods in 2017 gave Amazon access to more than 460 physical stores, and a way to diversify the selection of foods purchased from this organic grocery purveyor. Consumers who wanted to buy organic milk at Whole Foods but dunk the Oreo cookies they bought from Amazon Subscribe & Save could have the best of both organic and CPG-branded products within a single platform — and delivered to their doorstep if desired. PYMNTS research shows that 8% of U.S. consumers order products using Amazon’s subscription service, which is the largest retail subscription service in the US.

Read further: Inflation Forces Change or Churn Dilemma for Subscription Companies

Buying Whole Foods also gave Amazon the chance to make Prime Member benefits cross-channel. Prime Members got discounts on selected items when shopping at Whole Foods. Over time, Prime shoppers could use their Amazon credentials to pay at checkout in certain locations. Amazon says it will be in more locations this year. Amazon Prime Day this year will feature 20% off groceries purchased at Amazon Fresh, which promises a two-hour delivery. Even Amazon Prime critics expect a robust turnout as consumers use Prime Days to stock up on grocery items that are on sale.

In addition to its curated selection of organic brands and locally-sourced products, the Whole Foods prepared foods section quickly became one of the brand’s most popular consumer draws, particularly for millennials. A 2019 study conducted by Whole Foods found that millennials would (and did) pay extra for responsibly-sourced foods, and more than half spent more on food that year than they did on travel. Whole Foods’ prepared foods section provided a healthy and convenient alternative to fast food options, even though paying for it contributed to its “Whole Paycheck” moniker. And just like those fast-food alternatives, Whole Foods added an order ahead for takeout option to the app so that customers could avoid waiting in long lines at the store to place an order.

Grocery Stores and Restaurants Have Gotten the Memo

Whole Foods isn’t the only grocery store to have grabbed onto the idea of grocery store as one-stop shop for all things food, including prepared foods. Kroger bought HomeChef in 2018 for $200 million and, in October of 2021, reported that the prepared food brand had surpassed $1 billion in annual sales as consumers sought a more cost-effective option to ordering food from aggregators. Kroger has also entered into two ghost kitchen partnerships, the first of which launched in LA in January of this year. Analysts report that adding HomeChef and their ghost kitchen partnerships has taken foot traffic from both fast food and grocery competitors.

In September of 2021,Walmart reinvented the idea of the mall food court by bringing nearly 30 popular fast-food brands under one Walmart roof in selected stores in the U.S. Walmart’s captive food court is the latest tactic used to keep consumers loyal to the category that accounts for 54% of its sales.

Inspired by its success in its Canadian stores with Ghost Kitchens, Walmart U.S. provides space to the Ghost Kitchens team, which provides the setup and a small team of chefs to prepare food according to recipes licensed from the fast food operators. Walmart customers are able to order ahead for pickup to go as they shop the store.

This food scope creep isn’t lost on restaurants, the early innovators of putting idle capacity to use with virtual brands and ghost kitchens. Although most restaurants have increased menu prices recently by an average of 20% to boost revenues, their costs have risen by an average of 30%, denting profits. Many restaurant operators have beefed up their loyalty programs and added subscription offerings in an effort to retain consumer spending. At the same time, they’ve explored ways to reduce costs by outsourcing logistics to the consumer using incentives to pick up rather than deliver.

See also: PYMNTS Intelligence: Restaurants Must Lean Into Digital Loyalty Programs

Grubhub claims that 41% of independent restaurants operate virtual brands, and there are a growing number of ResTech players that simplify the process for restaurants. Fourth-generation restauranteur and Nextbite CEO Alex Canter explains that local restaurants can create menus around delivery-friendly crowd pleasers to open new revenue streams for restaurants that may have one or two key signature dishes and the capacity to make and deliver them. Nextbite is also creating unique product bundles like the Cody Ko Dessert Club, which gives local operators the recipes and branding needed to provide those selections.

Read more: How a 91-Year-Old LA Deli Inspired the Launch of Next-Gen Virtual Kitchen Concepts

The Whole Foods – and Food – Opportunity

Whole Foods operates more than 483 stores in urban and suburban locations where the population demographics skew towards those who value the health benefits of organic foods and are willing to spend more to get them. Just like every other grocery store, its suburban locations are strategically placed within a 15 minute drive for most living in the surrounding areas.

Many of its suburban locations have coffee bars and other restaurant-like amenities. The Whole Foods Bryant Park store in New York has a couple of restaurants, a coffee shop and a separate dining place to eat prepared foods for lunch or dinner. Its physical footprint is designed to offer utility beyond a place to buy groceries.

Today, industry research shows the sales of prepared foods on the rise as busy consumers opt for convenience and eating at home without having to cook a meal from scratch. It also appears that the ripple effect of increases in restaurant food prices is not only causing consumers to trade down their choice of restaurant, but to swap restaurants entirely for eating prepared meals bought at the grocery store at home. Obviously the severity of the macro headwinds of inflation could impact all of the above.

Like every other platform today, Amazon and Whole Foods seek ways to monetize idle capacity and maximize profits. For Whole Foods, that’s using the popularity of its prepared foods business, its kitchens and chefs to launch virtual brands — or license recipes from others who pass their organic vetting to expand their prepared food options. It also means leveraging third-party online ordering infrastructure and/or their last mile logistics to get products delivered to the homes of the customers living 15 minutes away — or incenting consumers to pick up their orders curbside. Amazon Lockers at Whole Foods give consumers a reason to stop by — and an incentive to stay for lunch or dinner or a coffee gets consumers inside the store to buy other things. All these purchase opportunities are eventually linked to their Amazon accounts, and a simple way to pay.

Amazon and Whole Foods won’t replace restaurants — but they could put a dent in traditional fast-food sales, and the takeout or delivery business of independent restaurants and the sales they represent for aggregators and operators. It could even challenge Starbucks for the position of its “third space” as more people look for great places outside of the house to meet people over a cup of coffee or a quick bite to eat.

Amazon and Whole Foods also represent the connected economy that I have been writing about since 2019 in action.

One of the most dynamic and lucrative ecosystems is that which integrates how consumers find, pay for and eat their food. The bright lines that once separated grocery and restaurant are blurring rapidly as grocery stores offer prepared foods and restaurants perfect delivery and expand takeout. Amazon and Whole Foods have the potential to erase those lines completely as consumers simply think about eating — and use their “eat” platform to find many different options for how to do that.

Hiding in plain sight all the time.