Bell Lab’s Picturephone was part of the exhibits at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City. (Image courtesy of The Porticus Centre)

An article published in the Harvard Business Review in August of 2009 posed a question that many airline and travel industry CEOs are pondering 11 years later: Will videoconferencing kill business travel?

The answer in 2009 was, probably not. The answer in 2021 is far less clear.

Image credit: Bell Labs and http://www.darkroastedblend.com/2015/01/videophones-from-future-past.html

Eleven years ago, video conferencing tech was in a very different place, even though the technology itself had come a long way from the commercial launch of Bell Lab’s Picturephone in 1964.

It was expensive — an investment that only big companies could afford to make, and mostly did so to make it easier for far-flung internal teams and corporate boards to meet without always getting on a plane.

It had the “fax” problem: The only way people could see each other was if the party on the other end had access to the same technology.

And it was location-dependent. Given its hefty price tag and IT requirements, the technology was installed in conference or board rooms and not individual offices. To use it, people had to gather in one of those rooms.

The quality was poor: Latency issues and sub-par picture resolution made it a less-than-ideal “face-to-face” experience — particularly when those without access to the tech had to join by phone or not at all.

In 2009, and over the decade that followed, the limitations of the tech meant that the most efficient way to do business was to hop on a plane to meet clients, get deals done and visit trade shows.

Even in the throes of the Great Recession in 2009, executives still traveled, even if their budgets were somewhat clipped. According to analysts, business travel spend dipped by only about 7 percent that year. By the end of 2019, business travel hospitality globally was a $1.4 trillion sector.

2021 is a whole different story.

Eleven years and a global pandemic later, the future of business travel is unclear.

Zoom put the power of a face-to-face meeting, using high-quality video tech, into the hands of anyone who had a connected device and needed to meet a client, prospect or team member face-to-face without having to be there in person.

After the initial shock and awe of the pandemic and lockdown of the physical economy in March of 2020, it was this technology that helped keep businesses moving and remote workforces productive. Business execs discovered that they didn’t have to get on a plane to move projects forward with clients, fill the sales funnel, close business or keep client relationships intact.

Even the court system shifted to Zoom for much of its work.

The friction associated with coordinating a place and time for busy people with conflicting travel schedules to meet in the same physical location was eliminated. Zoom made it possible for executives to be more accessible.

And since everyone was in the same boat — not being able to travel but with the same urgency to connect and do business — there was a mutual incentive to the tech, as well as the meetings it supported, effective.

Predictably, the segment was decimated in 2020 as government restrictions on travel, travel quarantine requirements, and executive concerns over health and safety put the vast majority of business travel on ice. In December of 2020, analysts predicted that the global market for business travel in 2020 would decline by 54 percent.

Sure, the outlook for 2021 and beyond is uncertain, but it is certainly grim. Although Zoom and similar tech platforms may not kill business travel entirely, they will hobble it materially — and those firms that depend on travelers to keep their own businesses alive.

According to a 2020 study of corporate travel managers conducted by the Institute of Travel Management, 38 percent report that business travel spending will decrease by 25 to 50 percent in 2021, while 36 percent say that it will be even more severe, with a 50 to 70 percent reduction. Eighty-eight percent cite the use of video conferencing tech as their top priority, while 80 percent cite a focus on travelers’ well-being.

Chief Financial Officers likely cite the well-being of their own bottom lines, as many have seen margins helped by reduced travel costs, often without the corresponding hit to their top lines, macro business conditions notwithstanding.

Firms have pivoted their business and marketing practices to reflect the new status quo — using digital tools and tech to fill the funnel, shorten the sales cycle and close business.

Online marketplaces that were once places for buyers and suppliers to discover each other — and then do business offline — will become payment-enabled, if they aren’t already. B2B eCommerce will ignite as digital tools, payments and credit offerings streamline those flows and suppliers commerce-enable their websites. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technology will allow buyers to digitally kick the tires. Trade shows will not only go online, but will become vertical marketplaces — pop-up shops online, if you will — for businesses to see the latest products and then order and pay for them. Payments will make all of these B2B commerce encounters easy, efficient and secure.

In fact, it’s something that the PGA has already done. More than 400 golf brands and manufacturers convened online last week to see — and buy, using B2B payments tech — the latest and greatest golf goodies for their clubs and retail stores.

Some say it will take until 2024 for business travel to snap back to 2019 levels. Airline CEOs see the vaccine rollout as the elixir for their industry and are bullish on the future of business travel, which is said to account for 12 percent of butts in seats, but 75 percent of airline profits.

But that optimism ignores the handwriting on the wall.

Their competition is no longer the other guy’s airline — nor the temporary hit to their business caused by a global pandemic. It’s the longer-term, secular shift to digital, led by the democratized access to a software called Zoom that has made their product less valuable.

Now, it’s not that business executives won’t ever hit the road again, but the friction associated with doing so will have to be worth the business outcome. And it must be good enough to persuade CFOs that the juice is worth the squeeze.

It’s just one example of the connected economy in action, showing how the power of technology, software and payments to forever change how people and businesses connect.

The Power Of Connections — And The Connected Economy

Even before the pandemic made it essential to shift to digital, what we do and how we do it was already becoming increasingly dependent on using digital platforms that make it easier for people, businesses or workers to connect — and without friction.

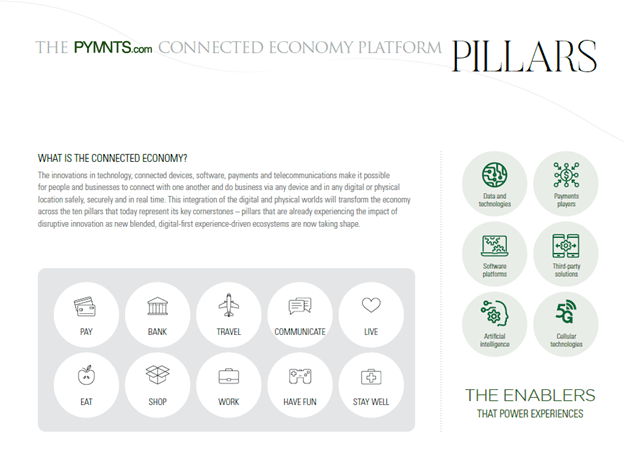

Every part of our lives is changing this way: how we eat, shop, pay, travel, bank, work, communicate, have fun, live at home and stay well. These 10 pillars of the connected economy fall into roughly three groups — even though the dividing lines between them are hardly sharp.

There are four essential services that people rely on to get much of the other stuff done: they have to pay, bank, communicate and travel.

There are another five that people use to operate a household, and to sustain and enjoy themselves. How they live is about managing their homes and daily lives. Then there’s how they eat and shop. And how they work, which most people need to do in order to do everything else.

Finally, people want to stay well and live longer, healthier lives.

Each of these pillars rests on a rapidly improving foundation of technology and businesses we call enablers: the cellular carriers, payment networks, cloud companies, software platforms and equipment makers that power other platforms.

Gradually, we will cease distinguishing between the digital and physical worlds, as almost everything physical will be connected and powered to digital to varying degrees. The marriage of digital and physical will lie at the heart of the transformations we’ll see in every aspect of our lives — and are already living through in real time.

The Connected Economy’s Fast Track

The connected economy got a jolt in early 2020.

It was already booming following years of slow, steady growth. Then the pandemic struck. Much of the physical world shut down. And most people and businesses were forced online. This resulted in a break in the trend line, which made a big jump upward — the jump discontinuity that I wrote about last spring.

That jump wasn’t just about going digital — it was about a break with the old ways that people and businesses used to connect, leading to something entirely new. As a result, many established digital platforms, including some with shaky futures, saw explosive growth. The duration of the pandemic, which now looks to be through most of 2021, will accelerate the shift to digital even faster. The convergence of the physical and online worlds will happen sooner.

The Connected Economy’s Matchmakers And Enablers

There are four main characters, shaped by economics and strategy, that will define and drive the future of the connected economy.

Matchmakers are the businesses that forge connections. They operate platforms, such as Instacart, that enable different types of participants, such as shoppers and grocery stores and consumers, to find each other and engage in a mutually beneficial exchange, such as getting their groceries picked, packed and delivered. The physical world, from ancient to recent times, was replete with them, from the medieval bazaar to speed dating. The connected economy mainly relies on digital ones.

Time is our most precious asset. We will only get so much of it. Many of us flock to any innovator who can save our time, for better things; give us more time, by expanding what we can pack into it; or give us something in return for our time, like money or entertainment. Digital matchmakers in the connected economy often help us make the most of our scarce time. Just think of the time you’ve saved by asking Alexa or Google to order paper towels while doing the dishes in the evening.

Dynamic competition is what always happens in the face of rapid technological change and disruptive innovation. It is all about companies, entrepreneurs and innovators figuring out what’s next and what others are up to, and making sure they come out on top and don’t get destroyed. Dynamic competition is what leads to the rapid creation of new products, and ways of doing things in the connected economy.

Tech ecosystems are multifaceted businesses, often consisting of one or more platforms, possibly interconnected, that engage in dynamic competition with each other and with challengers. They are often anchored in one area where their innovations put them on top, and then use their leverage to leap into new areas and compete with other tech ecosystems.

Big Tech – Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google and Microsoft – are increasingly challenging each other in their existing businesses, but more importantly, are trying to win the races for many entirely new ones.

The connected economy would not have been possible without three key enablers whose rapid improvements have accelerated its rapid spread through the nooks and crannies of commerce, work and living.

The oldest enabler is digital payments.

Putting the card credentials people were accustomed to using in the physical world in their mobile apps made it possible for ridesharing companies to provide the magical experience where they don’t have to pay at the end of a ride, but just open the door and leave. The pandemic has accelerated the shift to digital, even for emerging countries where cash remains the dominant payment method, while giving businesses the incentive to finally bring the “Uber experience” to consumer and business payments.

Then there are software platforms that provide common services to applications and a standard environment for the applications and users. Some of these are familiar names, such as Android, but others, such as Apache, labor in obscurity in the guts of the connected economy.

The gradual convergence of the physical and digital worlds began with the deployment of 3G cellular networks, and then, importantly, the 4G network, which enabled people to access fast, reliable internet service pretty much anywhere, anytime with a smartphone. With the 5G networks that are rolling out, almost every place in the physical world will have high-speed internet connections, where apps and other software will be able to provide digital services everywhere, anytime.

These enablers do not provide a traditional foundation that is permanent and longstanding. Each is going through disruptive innovation, which is making them better. If history is any indication, new enablers will likely emerge, as Android did in 2008. The enablers provide a foundation that improves, shifts shapes and propels innovation on top of it.

The Journey

Our journey into the connected economy began in earnest in late 2009. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 — and the birth of the apps ecosystem a year later in 2008 — inspired an entirely new class of innovator that started the decade of the 2010s with a brand-new toolkit. Armed with new tech, mobile devices data and the cloud, they fast-tracked the shift from what was then still a largely analog world to the app-based economy that is our reality today.

That combination of smartphones and apps has changed how people and businesses interact within and across each of the 10 pillars of the connected economy.

The connected economy will be the result of the full force of the Internet of Things (IoT) in action.

Just about every device will be connected to the internet and capable of enabling a transaction — between machines, people, businesses and every possible permutation in between. In this new connected economy, we will find ourselves living in a world in which new networks, intermediaries and enablers will emerge — and change what we used to call the payments and commerce status quo.

In many ways, the last 11 years was the warmup act for the transformation that we have seen accelerate over the last 11 months — the transition from an app-based economy to one in which connected ecosystems aggregate commerce experiences and enable transactions across channels, devices and environments.

Payments is powering many of those shifts — and the new business models that have emerged.

According to the latest PYMNTS survey of U.S. consumers, 115 million adult consumers — 45.4 percent of the U.S. adult population — have shifted to digital. They are doing less in the physical world and more in the digital world for the same activity since March of 2020, including buying retail and grocery products and food from restaurants. And 80 percent of them — 92 million — say they’ll stick with those digital-first habits. Not only have they broken with the status quo, they don’t want to return to it. Digital payments, alternative payments and credit methods have made it easier for businesses, even those on Main Street, to transact with a consumer who wants their products, but may not want to go to the physical store to get or pay for them.

The Connected Economy Roadmap

In the first year of the decade of the 2020s, all of us were collectively left to navigate our way in a world for which there was no playbook. Times remain tough for many.

Yet, experience teaches us that opportunities will emerge for innovators to devise more and better ways of doing things in the connected economy, especially as technologies improve. They will be able to tap into the 115 million U.S. consumers — and hundreds of millions more the world over — who have become increasingly acclimated to online life, using platforms and connected devices that save them time, keep their interactions safe and secure, and deliver a far better experience.

Just take Zoom, where I started.

Yes, this is how business colleagues are working with each other, each sitting in their spare rooms, usually dressed down, sometimes in hoodies — but getting the job done, regardless of the dress code.

But it is also how doctors are visiting their patients. Zoom, along with other video platforms, is part of what’s driving health tech and the move to telemedicine. Payments innovators are integrating flexible payment arrangements into those experiences.

It’s how teachers and students engage and learn.

Video platforms are how retail sales associates stay connected with their clients and show them new things to buy.

And how judges hear cases and conduct pre-trial hearings and lawyers take depositions.

It’s how real estate agents show houses and buyers buy them, sometimes even without ever stepping foot on the property until they buy it, and from anywhere in the world.

Video platforms are how bankers are engaging with their customers, and how interior decorators are helping clients feather the nests where they now spend nearly all of their time living and working.

And how orchestras perform for their virtual audiences without leaving their homes.

The connected economy, through innovation and the inspiring labors and ingenuity of entrepreneurs, will, in the end, make the world a better place — and will make the ’20s the roaring decade that we imagined just a year ago.

It’s those stories, and the connected economy framework, that will define that path.