When Did the Job Market Get So Weird?

Depending on who you ask, the latest jobs report was either good, bad, historic, disastrous or something in between.

One thing most market watchers agree on is that the concept of work, a job, labor, wages — however you want to view it — has changed. And not just incrementally, but in ways that were unimaginable a generation ago.

Among the weirdest stories of 2022 that are now spilling over into 2023: the mashup of high inflation and wages amid a 50-year low in unemployment; the inability to fill 10.5 million open jobs at a time when struggling households need the money; and the Silicon Valley jobs guillotine busier than it has been in 15 years.

This is work, version five-dot-whatever, as the connected economy and COVID-19 combination have created a mass migration away from office buildings and into home offices, at least for so-called “knowledge workers” — simply defined as anyone who just needs a laptop and an internet connection to earn their pay.

It’s hard to know where to start, but let’s go with work from home, or hybrid work, which sounded great three years ago. Now we’re kind of stuck with it. Turning to the data, PYMNTS’ “12 Months of the ConnectedEconomy™” report sums it up thusly: By the third quarter of 2022, “58% of consumers worked in a digital-only or hybrid work environment. This means 8 million more consumers were part of the remote workforce in November 2022 than just one year earlier.”

What gives? It’s a combination of factors. A good many companies simply abandoned long-term commercial office leases as a summer spike in hybrid work that initially looked like a summer phenomenon just carried on.

Hey, we get it. Millions read Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky’s January 2022 blog post about the rise of the work-from-anywhere (ideally in an Airbnb rental) “digital nomads.” It sounded cool, even too good to be true, but even with almost two years of remote work under our collective belts at that point, the great return to office story has yet to materialize.

Where’s it all heading? Some CEOs are ordering people back to offices (assuming they still lease or own one), while others have admitted defeat — or accepted it — and gladly pocketed the savings on real estate spending.

See also: More Than Two-Thirds of US Workforce Now Work From Home or Hybrid

Job, No Job, Second Job

Turning to the bizarro portion of the week’s job-related insights. On the one hand, you’ve got news sites like Business Insider blaring headlines like this one: “Over 150,000 Tech Workers Have Lost Their Jobs in 2022.” Few tech companies were untouched by job cuts, which market watchers chalk up to the two-year COVID tech hiring boom that went bust in year three as inflation halved the valuation of category killers like Amazon.

Speaking of which, Amazon CEO Andy Jassy tried to break it to folks gently in his Wednesday (Jan. 4) blog post, explaining to employees that the expanded 18,000+ headcount cut would make the business stronger.

“Companies that last a long time go through different phases. They’re not in heavy people expansion mode every year,” Jassy wrote, adding there is a need for fellow Amazonians to stay “scrappy” as they work through the present fog and find a way to do more for customers at a lower cost.

What makes all this so odd is the staggeringly low 3.5% unemployment rate.

The same day that Jassy’s message went out, the latest Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) said, “On the last business day of November, the number of job openings changed little at 10.5 million.”

Said another way, nearly 11 million jobs are sitting unfilled while Big Tech hemorrhages skilled workers, and U.S. households are engaged in an epic, belt-tightening struggle with inflation. They need money. They need second (and possibly third) incomes. The jobs are out there, just not at Amazon PXT or Apple stores. Or Salesforce. Or Meta. Or Snap.

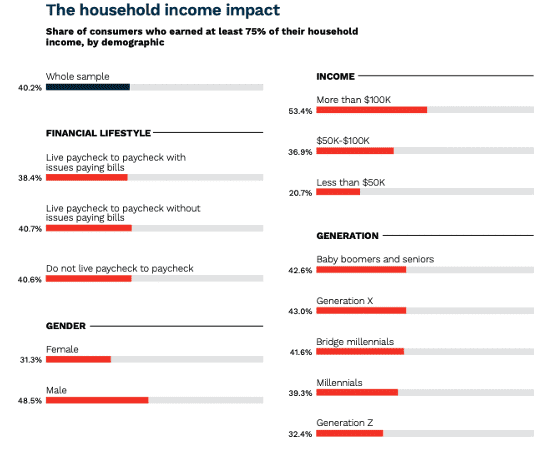

According to the “New Reality Check: Paycheck-to-Paycheck Report: 2022 Year in Review,” the long-running PYMNTS and LendingClub study series that’s exposed the precarious financial position that has now engulfed over 60% of Americans, “Struggling consumers are the most likely to say they are the sole income provider in their household,” which means they’re teetering on the edge, but not necessarily getting that needed second job, even though there’s plenty to be had.

Add in other peculiarities like “the great resignation,” a concept that is best captured in the labor participation rate that is struggling to get back to 65% — meaning roughly one-third of able-bodied Americans have tapped out of the workforce and the much-feared recession hasn’t even hit yet.

Where are we going with all of this the first weekend in January? Who knows. But one thing is for sure: Never has the word “uncertainty” been more overused — or appropriate — to describe the mix of known unknowns befuddling the New Year’s world or work.