Latest Consumer Data Shows Expenses Grew Faster Than Income in September

The latest data from the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis revealed that consumer spending outpaced income growth in September.

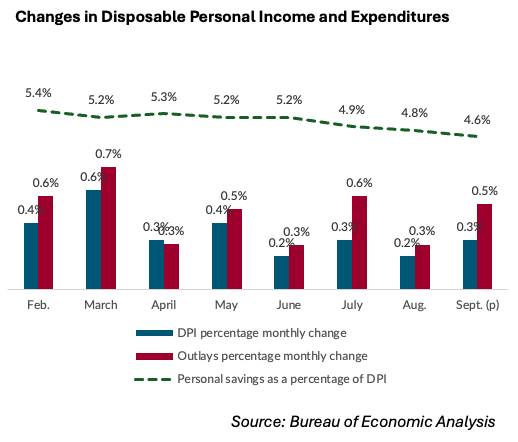

The news may be a boon for consumption and, by extension, merchants. However, the personal income and outlays data indicated that a decrease in the share of savings as a percentage of personal disposable income may raise questions about whether it’s all sustainable.

Third-quarter GDP growth, at 2.8%, rested in large part on consumer spending.

The data released by the BEA Thursday (Oct. 31) gives more granular insight into September’s trends. Consumer spending was steady. Personal income and disposable personal income rose 0.3%, more than the 0.2% measured inflation. The read-across, with 0.5% growth in outlays (spending), is that consumers bought more in September.

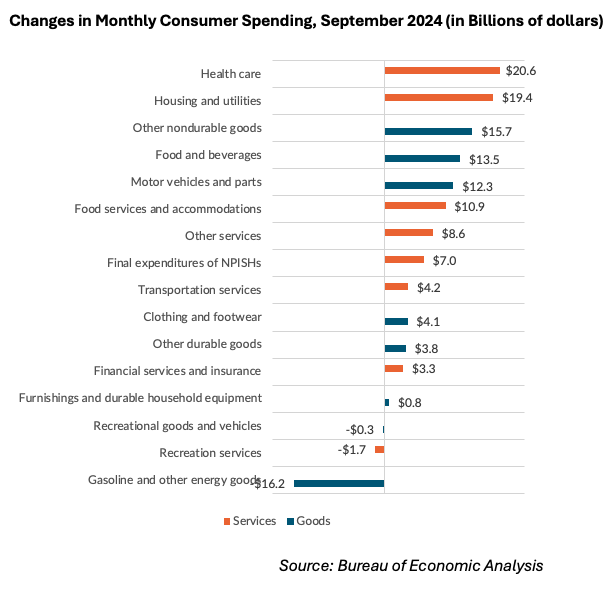

Drilling down into the $105.8 billion growth in consumer spending, both general categories — goods and services — saw gains.

As for the categories themselves, healthcare, housing and nondurable goods (such as prescription drugs) saw the largest growth, as measured in dollar terms.

The expenses showed that key everyday essentials are still the bulk of what consumers are using their paychecks for. Larger-ticket items, such as vehicles and furnishings, are seeing combatively muted outlays, and even some declines.

Personal savings have dipped from recent highs as measured as a share of disposable income, where the peak had been more than 5% and now stands at 4.6%. This could imply that consumers are tapping into their savings to cover everyday expenses.

The PYMNTS Intelligence report “Boomers Are Leaving the Credit Market” found that 40% of consumers earning less than $50,000 a year reported they do not have readily available savings, which might lead them toward credit to offset those cash cushion pressures.

PYMNTS Intelligence also found that almost 60% of consumers relied on credit products to pay for groceries last month.

Earnings results from the likes of Mastercard and Visa this week have taken note of healthy credit use.

Fewer consumers now have a smaller buffer for unexpected expenses as the savings rate slows, the data hinted. Combined with the slowing rate of incomes, these trends underscore a precarious balance between robust consumer spending and potential financial vulnerability.