Who Will Be The Consumer’s Everyday App?

Everyone wants to be the consumer’s everyday app – the “super app” to rule them all, the front door into the goods and services consumers use as they go about their day.

It’s what WeChat is to the Chinese consumer and what Grab and Gojek would like to be for those living in Southeast Asia. It’s what every Big Tech and FinTech player – Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, PayPal – aspires to be, too, even if they haven’t publicly said so. Every new function, feature, acquisition and platform extension is an attempt to add another layer of functionality to capture more of the consumer’s time, attention and spend.

Everyday apps don’t have to do everything — rather, their value is about enabling a more streamlined connection to the activities that are part of the consumer’s everyday journey.

The appeal in being that front door is obvious: the ability to monetize access to the consumers who use it and the interactions that happen inside that ecosystem.

But it’s an ambition made more challenging by multiple apps from different providers, which have eliminated much of the hassle once associated with finding and accessing those products and services.

And more than half of consumers in the U.S. are, today, more or less ambivalent — even though a third of them say it’s something they’d really like to use.

The Everyday Apps

For the last decade, consumers have lived their digital lives hopscotching between a series of icons on their smartphone home screens. Those apps – and now an increasing portfolio of connected devices beyond smartphones – have given consumers a digital front door to services that before required a friction-laden physical world interaction.

Today, consumers use bank apps for checking their balances and paying bills, investment apps for managing their money, payments apps and digital wallets to store balances and pay for things they want to buy, ride-hailing apps for getting around town, reservation apps for dining out, delivery apps for eating in, travel and hotel apps for booking trips, transit apps for public transportation access, merchant apps for shopping, email apps for work, calendar apps for organizing schedules, messaging apps for texting with friends and colleagues, social apps for keeping up with friends, streaming apps for watching videos, dating apps to find romance, streaming apps to listen to music and play games, digital content apps for reading news and books, search apps for getting information, map and navigation apps for getting directions and fitness apps for tracking their health.

In fact, in June 2019, a PYMNTS study of 1,037 U.S. consumers, a representative sample of the mobile-using public, found that consumers access one of more than 44 different apps the very first thing when they wake up every day across those different categories – from email to their calendar to mobile banking, social media, shopping and messaging apps. When asked which app consumers first look at when they wake up in the morning, it was either a social media app like Facebook (or Instagram if they are millennials) or text/email to organize and plan their days.

Those apps, however, largely compartmentalize access to everyday activities. It has become more convenient to check how much money is in a consumer’s checking account via a banking app, find what they might want to buy, then determine whether their favorite retailer has the item available for in-store pickup and how long it might take to drive to the store to pick it up after ordering online.

It takes four different apps and four different interactions across those apps and many minutes to close the loop on that single flow.

But a huge improvement, for sure, over the old-fashioned way of 20 years ago, when that single flow required calls to the bank and trips to the store – and much, much more time, with a lot more uncertainty of the outcome.

So, PYMNTS wanted to know if consumers, after a decade of living in a multi-app, icon-based world, wanted more – the everyday super app that could streamline those flows.

When we asked them that question, we made it clear that this app would not necessarily require them to give up the apps they use today, but would simply make it easier and more efficient to access the services or products those apps provide.

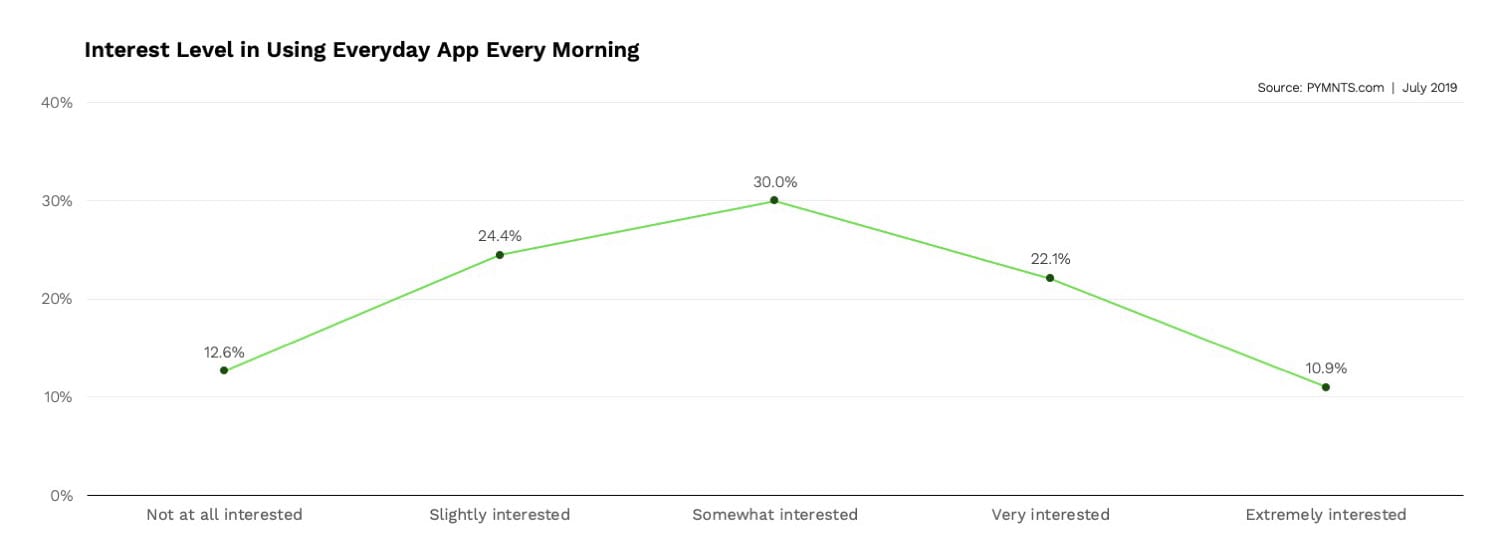

Here’s what we learned: About a third of people love the idea, about half seem somewhat interested and a few absolutely hate it.

Trust and the Everyday App

Just about a third of the consumers we studied expressed strong interest in the “app of apps” concept, with 11 percent (10.9 percent) expressing an extremely strong interest. Only 13 percent of the consumers said thanks, but no thanks. The majority, 54.4 percent, were on the fence – they were a little or somewhat interested in having a single app as the gateway to a more streamlined interaction with the many apps they use every day.

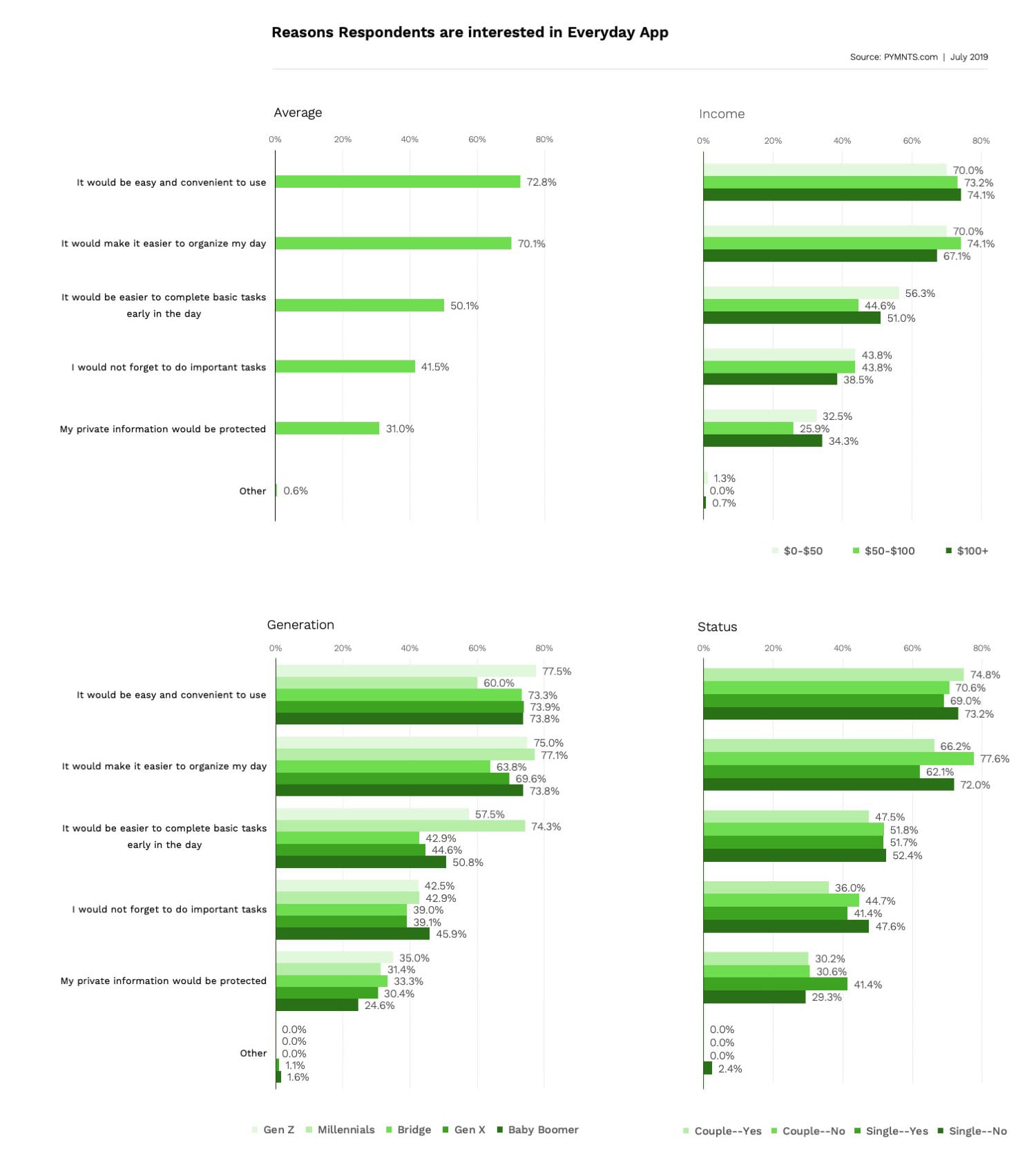

Seventy percent of those with a strong interest said it would make it more convenient and easier for them to organize their days and remember important tasks. It’s a sentiment that’s more important to bridge millennials (30-40-year-olds), Gen Z and Gen X than it is to millennials or boomers.

Those who are on the fence or aren’t at all interested are concerned that front-door access to all they do leaves them vulnerable to hacking and data privacy issues. The front door needs to be secure – for everyone, but especially that segment – and it needs to belong to someone who is not only familiar to them, but who they trust.

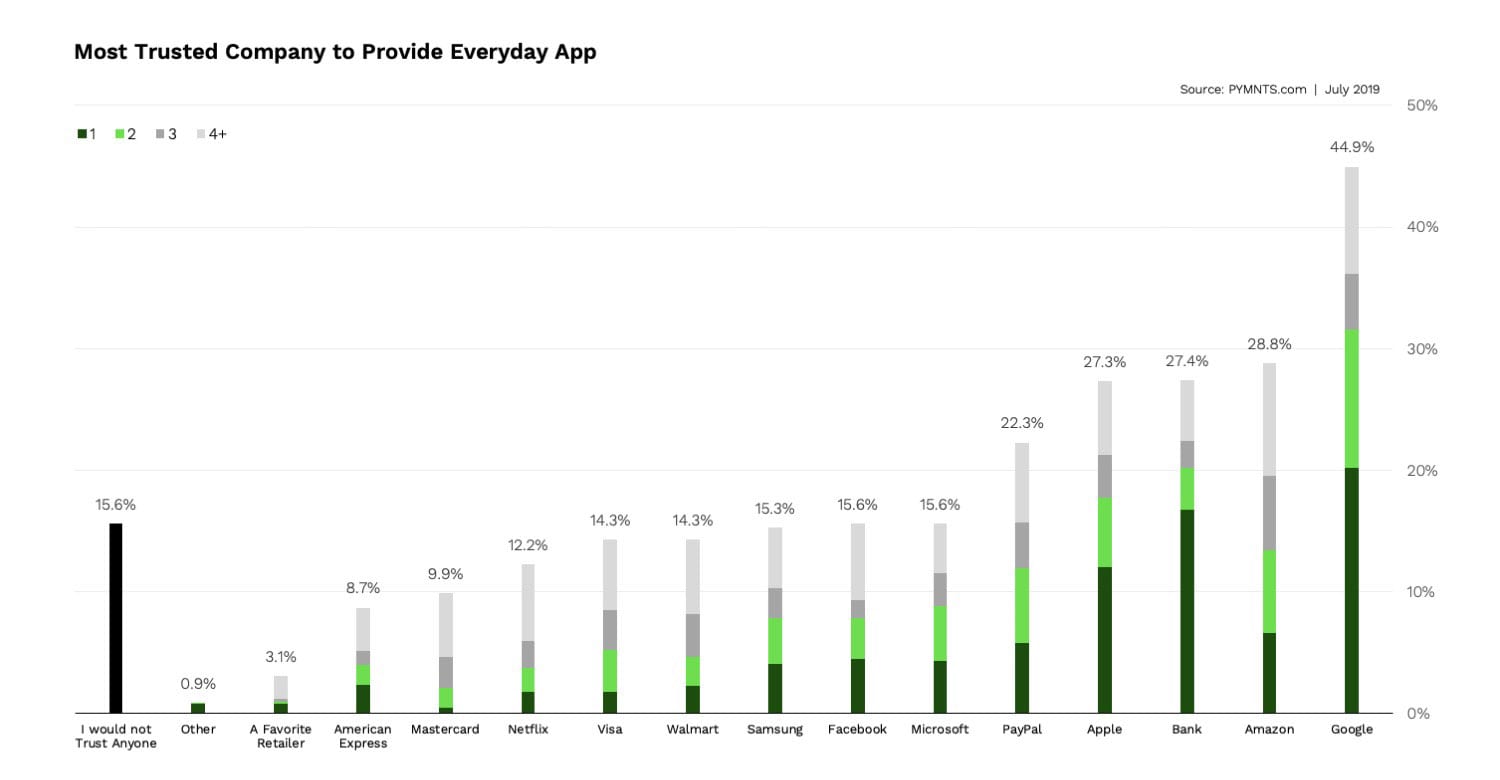

When asked who that is, consumers say it’s Google (45 percent), followed by Amazon (29 percent), Apple (27 percent) and PayPal (22 percent). Facebook, Samsung and Walmart are favored by 15.6, 15.3 and 14.3 of consumers, respectively – more or less a statistical dead heat.

When measured by interest, the one-third of consumers with a strong interest in using an everyday app want Google, Amazon or Apple to deliver it – and in that order.

Maybe you’re not surprised.

Today, the consumer’s frame of mind with respect to the everyday app provider seems very correlated to the breadth of apps they interact with during the course of their everyday activities, and who provides that access.

For more than 60 percent of consumers in the U.S., that’s Google. Those consumers live inside a Google ecosystem on their smartphones, and use a variety of Google apps daily to get information – Maps, Search, Shopping, YouTube and messages via text and email.

But even those who live outside the Android ecosystem use the Chrome browser app, Maps and Waze and have Gmail accounts on their iPhones. When it comes to the overall utility of an everyday app, Google is top of mind because it already checks a lot of those everyday boxes.

The same holds true for Apple and iPhone users, whose perception of the everyday app is much the same. Their iPhones, courtesy of Apple, provides access to the apps ecosystem they have assembled on their mobile phones.

Amazon’s relationship with the consumer, on the other hand, is device- and platform-agnostic. It also makes its relationship with the consumer very portable.

Consumers have a commerce relationship with Amazon, independent of the devices they use to access it. Amazon’s app is the front door to a relationship that has captured roughly 50 percent of online consumer retail (we have our doubts about their revised downward market share calculations) and one in which transactions happen in an integrated shopping, payments and fulfillment experience.

Amazon, through its Prime membership, also gives consumers more access to services that go beyond its roots as a traditional retailer, and even outside of its app.

Streaming video and music content are available from Amazon, but the consumer doesn’t have to be inside the Amazon app to experience it. The same holds true for Amazon’s expansion into grocery and food with their acquisitions of Whole Foods and PillPack. Both stretch the boundaries of traditional retail in terms of their products and the channels in which they touch consumers – but all wrapped inside of an Amazon experience.

Regardless, Amazon’s ecosystem, by way of the Amazon payments credential, provides users with an integrated, largely consistent shopping and payments experience, and an efficient way to receive what they buy. That’s also true for some, but not all, of the off-Amazon merchants that accept Amazon Pay as a payments credential on their own branded sites.

Everyday app contenders, then, must determine who is best-positioned to not only create that front-door access for consumers, but also to give them a credential that unlocks it and lets them transact efficiently inside of that ecosystem.

What Does an Everyday App Have to Do?

The consumer’s everyday journey consists of a complex maze of activities, most of which touch money and determine how and where consumers spend it.

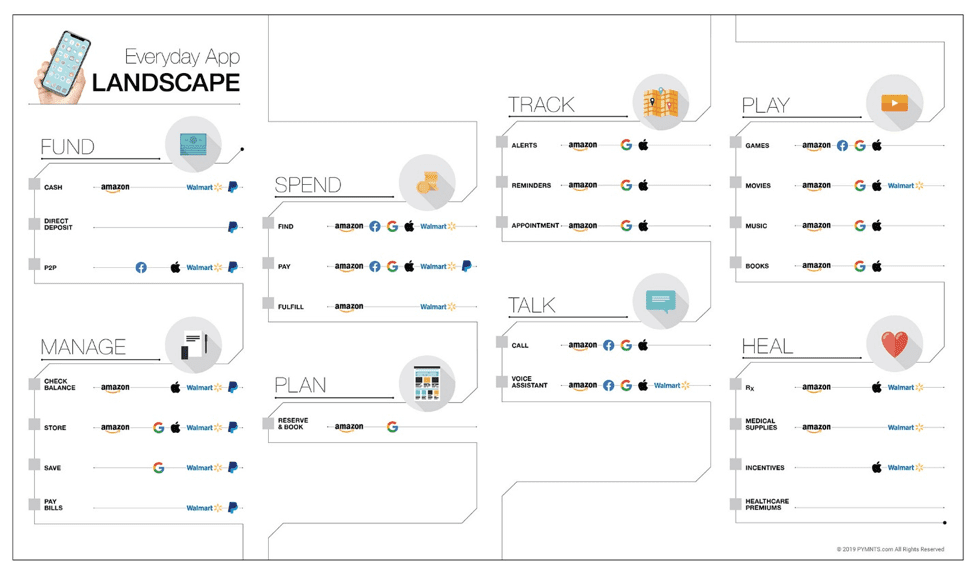

PYMNTS has taken a shot at breaking down everyday app functionality into a few buckets. These buckets capture the types of activities that might add value to consumers based on the everyday journey – and the apps consumers told us they like to use.

There are a few basic check boxes.

From the consumer’s perspective, an everyday app must provide a more integrated way to keep tabs on planning, managing and spending funds, and even enabling receipt of funds from other sources. It needs to streamline the tracking of reminders and alerts across a variety of activities – bills to be paid, appointments to be kept, deliveries to be received, important dates to remember and what friends are doing. It needs to be multi-modal and bi-directional, and should enable communication by voice and text as appropriate.

Then there are the value-adds that give consumers more of a reason to live inside of an everyday app ecosystem.

Increasingly, such an app must enable access to a variety of entertainment options like streaming services, games, music, books, video, live programming, reservations and bookings. And it should even provide access to healthcare services like the purchase of medical supplies, prescription drugs and other wellness services.

The leading everyday app contenders – Google, Apple, Amazon, PayPal – are all at different places along that continuum, which this everyday landscape shows.

The key takeaway is that no one has it all. Yet everyone is leveraging their assets to find ways into the areas they don’t yet have.

Apple is investing in content and Google has revamped Google Shopping. Amazon is investing in food delivery platforms like Deliveroo, spending nearly a billion dollars on enabling one-day shipping and expanding Amazon Pay off Amazon. PayPal is enabling payouts into PayPal accounts for gig worker pay, has expanded Xoom to 32 countries and has launched its commerce platform in an effort to add more value to its merchant and consumer base. Facebook is pushing into payments, has launched Portal and would like to get a whole new payments system, Libra and Calibra, off the ground.

Apple is investing in content and Google has revamped Google Shopping. Amazon is investing in food delivery platforms like Deliveroo, spending nearly a billion dollars on enabling one-day shipping and expanding Amazon Pay off Amazon. PayPal is enabling payouts into PayPal accounts for gig worker pay, has expanded Xoom to 32 countries and has launched its commerce platform in an effort to add more value to its merchant and consumer base. Facebook is pushing into payments, has launched Portal and would like to get a whole new payments system, Libra and Calibra, off the ground.

Both Google and Amazon are investing heavily into AI and voice in the hope of tilting the everyday app opportunity their way.

Getting to Everyday

A third (33.7 percent) of all consumers say they’d like a voice assistant to be integrated into their everyday app experience. Another 10 percent say skip the app and go right to voice. That group wants a voice assistant to be their everyday app, and they want it integrated with their voice-enabled speakers at home.

For the nearly 44 percent of consumers who want voice integrated into their everyday app experience, it’s not hard to understand why.

It’s much easier to ask Alexa or Google Assistant to do the heavy lifting of figuring out how to get things done, or be the friendly nudge to getting things done, then to constantly tap and scroll a series of apps.

And both Amazon and Google are both investing heavily to be that voice-activated front door.

Amazon is integrating Alexa into tens of thousands of third-party devices and bolstering Alexa’s skills to include searching for content that might otherwise be diverted to Google. Amazon is offering incentives to homeowners to make their homes smarter with Alexa – and third-party devices to make their cars smarter, too. Amazon gets the fact that they don’t have search covered – beyond searching their platform for what to buy – and is using the Echo and the Echo Show to prompt users to turn Alexa into their helpful everyday assistant.

Google, on the other hand, has to crack closing the loop on commerce. Google Shopping is an effort to keep searches for products inside the Google ecosystem, and to ensure an easy payments experience with credentials stored in the browser. Google is also integrating commerce into searches for flights and food and continues to expand these contextual commerce use cases.

But Google has a long way to go to catch up with Amazon, which has nailed, literally, the last mile to eCommerce – and is expanding its commerce reach into more and more of the segments that consumers use every day.

And Alexa has more than a running head start in the voice-activated world.

For the consumer who wants an everyday app, it seems clear that they want to take it everywhere, all of the time. Mobile phones will remain important, but will become relatively less so as more connected devices emerge to allow integrated, seamless access to app-enabled activities. And over time, consumers will use voice as the bridge to that everyday app experience.

That makes Google and Amazon – those with the No. 1 and No. 2 pole positions today – the real contenders for delivering the everyday app experience.

They are the two platforms that now cross channels, software platforms and connected devices, with voice assistants that have taken up residence in the consumer’s homes.

And since no single platform has it all, it will be fascinating to watch the everyday app game play out. It’s a game that will become more strategic as players assess where they have gaps and who can most effectively help close them.

And a game that may force everyday app contenders to consider more strategic partnerships than massive acquisitions on the big everyday app chessboard – particularly in a world in which regulators would like Big Tech to get smaller, not larger.