The Great Online Innovation Pile On Of 2017

There seems to be an awful lot of piling on these days on the big online platforms.

Startups are piling onto Facebook, claiming that they steal their good ideas.

As The Wall Street Journal reported last week, the founders of live video chat service, Houseparty.com, said they thought they were being invited into Facebook’s offices last year to discuss a potential acquisition. Shortly after that meeting, the article says they were told by Facebook that talks would proceed no further. Then, the House Party team says they all of a sudden started to see Facebook’s own promotion of a standalone video chat app that will launch this fall. The WSJ story suggested that Facebook CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, is so obsessed with losing ground to anyone, including a slew of small startups, that he has set up an internal surveillance program that “actively monitors” what said startups are doing so that Facebook can track and then “squash” the competition.

Traditional grocery stores are piling onto Amazon, claiming the acquisition of Whole Foods will tip the balance of grocery buying power in Amazon’s favor.

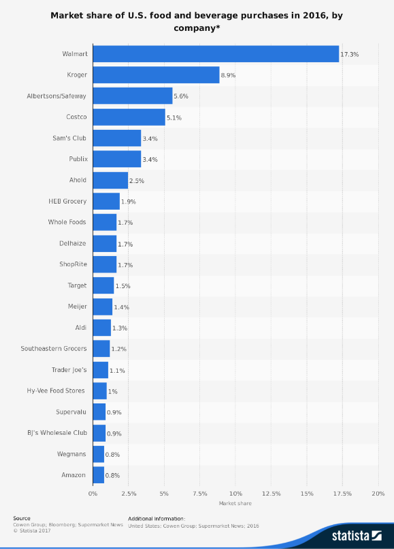

This one is particularly amusing. Take a look at this chart, which lays out grocery chain market share. You will observe grocery, as a retail category, is very fragmented. Walmart has the largest market share at 14.2 percent, the next biggest player is Kroger at 7.2 percent. If you are having trouble finding Whole Foods, I’ll help you. They are down near the bottom at 1.7 percent. Amazon you’ll have no trouble finding, since they reside at the bottom at an .08 percent share.

But two short years ago, article after article was piling onto Whole Foods as basically the biggest loser in the grocery sector. Its “Whole Paycheck” image combined with the rise in availability of organic foods in more traditional grocery stores put pressure on its stock, which was in the dumper, and the management team to do something to turn things around.

The news that Amazon would buy Whole Foods in June caused the collective media to suffer a mild dose of amnesia (and the market share realities to been thrown to the wind) after having harangued Whole Foods for two years to get its act together. It was enough to set a series of reports in motion suggesting that Amazon/Whole Foods would use its combined whopping 2.5 percent share of grocery to disrupt the balance of power in the grocery industry, post acquisition. The narrative over these claims of anticompetitive behavior has escalated to include discussions by Members of Congress to ask the Justice Department to review the merger on those grounds. You don’t even need to be an antitrust expert to get that this is a baseless claim.

The regulators in Europe piled a $2.7 billion fine onto Google, claiming that their product carousel ads created an unfair advantage to small guy retailers who didn’t have the money to advertise.

I’ll point out that those retailers did, apparently, have the money to hire lawyers.

I wrote a whole piece about this several weeks back, where I did a bit of my own piling onto the EU for the reality-challenged arguments behind the fine and its new regulations of Google. Somehow the folks in Brussels missed the fact that Amazon has become a massively successful search destination for product search. They seemed to be living in the last decade, when people really did just use Google or Bing to look for products.

The media is now doing all kinds of piling onto Snap, claiming that they’re not worth the paper the IPO was printed on.

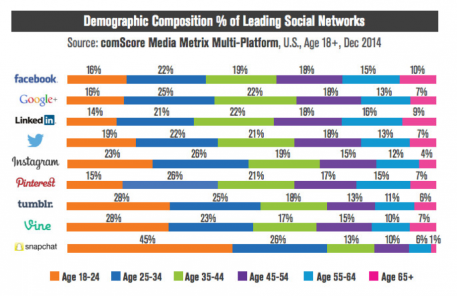

What a difference two years makes. In 2015, the tech media was gaga over Snap and its ability to corral the so-called most valuable eyeballs in media: the millennial. This comScore chart shows that audience breakdown and made the tech press and event circuit rounds in force. Media companies, in the meantime, shoveled tens of millions into Snap in the hopes of selling to a generation whose brand loyalty is about as fleeting as Zsa Zsa Gabor’s affection for each of her nine husbands.

That year, the stories about Snap were those of a hotshot, good-looking cool kid startup, Snapchat, taking on aging social network, Facebook, by giving those highly coveted millennials a mobile app to hangout and chat where their parents couldn’t find them. Investors put $2.65 billion into Snap since it started in 2012, and its IPO in March of 2017 raised $3.4 billion more.

Since opening its performance to public scrutiny via its now-public filings of its financials, the stock has lost more than 21 percent of its value. And the once-adoring tech and analyst community have turned ugly. Even its lead underwriter, Morgan Stanley, sent a note to investors that began with “We have been wrong …” and downgraded the stock shortly recently.

A venture that was once seen as Facebook’s biggest threat is now viewed, five months after its IPO, as toast at the hands of the company that two years earlier was viewed as highly vulnerable because of it. Ignoring, of course, that in its first months as a publicly traded company, Facebook lost about half of its market value and struggled to convince investors for more than a year of its ability to skate to where the puck was going — mobile.

It’s Not Easy Being Big

All of these stories, which are just the tip of a very deep iceberg, emerged over the last few months and fueled an insatiable media spin machine by ginning up the modern day David and Goliath stories of which that people just can’t get enough.

We all know the Biblical story of David and Goliath: Little boy named David, armed with only a slingshot and a few rocks, topples big heavily armored, sword-carrying evil giant named Goliath and saves the day for the Israelites. David did the deed by catching Goliath off guard: using a slingshot and a rock and not a sword to cause him to topple — then slaying him by using Goliath’s own sword.

It’s an inspiring story — and one that gets many an innovator out of bed to fight the good startup fight, even in the face of insurmountable odds. Harvard Business School professor, Shikhar Ghosh’s research says that three out of every four venture-backed startups die, and 95 percent of them fail in the sense that they never deliver the expected return on their investor’s capital.

It’s also a metaphor that only works well if the competition is so cut and dry that it’s easy to define.

Which, given the complexities of today’s commerce ecosystem, is neither.

A Goliath by Any Other Name

Google and Amazon and Facebook and Apple are all competing with each other — and many other Goliaths — over eyeballs and the revenue that follows them. They are all competing in an ecosystem where there are multiple Goliaths to slay at any given moment.

Take Google.

When Google was just about search, its competition was Bing and a few other now-forgotten search engines. But today, Google is “just a search engine” in much the same way as I am just a female. Today, Google’s competition is everything from Amazon for product searches and virtual assistants living in voice-activated ecosystems and hardware, to Facebook for mobile ad spend, to Apple over operating system share for Android and app developers for Google Play, to WeChat for eyeballs worldwide and all of the many digital acceptance marks for Android Pay as it strives to give users a new way to pay.

When Facebook was just a social network with a clever ad model, its competition were just other social networks, like MySpace. But Facebook was never “just” a social network. Facebook — and now Instagram, Messenger and WhatsApp — are all duking it out with Google for mobile ad dollars and search, Snap for millennial eyeballs and engagement, Amazon for commerce — and, if rumors are correct, virtual assistants and the hardware to host it, publishers for eyeballs on News Feed content and WeChat and every other messaging platform, for messaging.

Then there’s Amazon.

When Amazon was just about selling books online, its competition was the physical bookstore. But Amazon has long since blown past its days of selling books and CDs. It’s a commerce platform with a marketplace of sellers that is competing with traditional retailers who don’t want to cede their place in retail to Amazon, Google and Facebook for search, Apple and Google for voice-activated ecosystems and developers, Microsoft for cloud computing, every digital wallet for payment on and off Amazon and Netflix for streaming content.

Snap used disappearing messages to capture the millennial’s attention — and her network. Its vertical format for photos and videos — consistent with how people hold their phones — was its differentiator and became the lure for advertisers who wanted to reach this hard-to-reach demographic. But Snap is a P2P network that just happens to use video and photos as its hook. It’s competing now with Venmo, Zelle and Square for P2P payments — and commerce more broadly, in addition to Instagram and Facebook for ad dollars and, it appears, investors who now suddenly don’t think it has the chops to scale as fast as they had once believed.

Survival of the Fittest

The Great Innovation Pile-On of 2017 seems to ignore the reality that no one player will emerge as “the winner” — as much as it’s what everyone wants to read about. It’s just not that kind of world anymore.

Facebook, Amazon, Google, Snap — and the many, many more that I didn’t highlight — are fighting for position against not just one competitor but many, given how their platforms have evolved over the years. Leveraging their assets and extending their platforms and finding new ways to innovate in an effort to keep a consumer with more options than ever to find stuff and buy stuff and share stuff and communicate stuff happily inside their own ecosystems is their only ticket to survival.

And, the more that the cloud and digital payments and connected devices expand the range of players and options for reaching that same consumer, the harder it will be to pick out the Davids from the Goliaths in the crowd.

The Great Innovation Pile-On of 2017 also ignores three other things: Nothing is forever, there are no sure things and sometimes things come full circle.

Sears was traditional retail’s Goliath until Sam Walton and Walmart emerged as retail’s biggest player in the 1980s. Walmart was the big Goliath before Jeff Bezos and Amazon used a slingshot to bring online shopping and one-click buying to consumers and topple Walmart’s once-vaunted position at the top of retail’s pecking order.

Nothing is forever.

Now, Amazon announced a month ago that it would sell Kenmore products on its platform, and the share price of Sears did something it hasn’t done in a while — move up. Amazon and Walmart are both vying for their piece of the retail pie, including one of Amazon’s latest volleys to team up with Sears.

Somethings things come full circle.

Looking back, there is one thing that seems certain about Goliaths. They eventually fall. And new Goliaths take their place. Microsoft was the king of operating systems, and as of 2005, Microsoft was the player that everyone thought was going to own the smartphone market and battle it out with Blackberry for the number one seed. Both of them never saw Apple and Steve Jobs, the David that at the time was all about iPods, coming.

That was only twelve years ago.

There are no sure things.