Financial Times columnist John Gapper got a check for a dollar in the mail which prompted him to write a piece that more or less portrayed the US as being total Luddites in the payments innovation department. Well, in a true case of payments patriotism MPD CEO Karen Webster couldn’t resist taking Gapper to task and providing her own payments’ reality check. You won’t want to miss this one.

Maybe it was the celebration of our independence on the 4th of July that got British columnist, John Gapper, annoyed enough with the US to write a piece in the FT last week that took our banking and payments systems to task. In that piece, Gapper claims that the US “lags behind badly in the basic infrastructure of retail banking.”

It surely wasn’t a critical look at what’s been accomplished in the US with respect to innovation in banking and payments.

His piece begins by describing a check he received from a New York bank for a dollar, a check that traveled by post 3500 miles across the Pond prompting Gapper to comment on the “quaintness” of the US system because we still use checks. He didn’t say what triggered the check so it’s hard to comment about why it was a check and not something else. Gapper used the example to contrast the US use of checks to the UK Faster Payments system that would have had the monies digitally transferred to his account and made available to him the same day. Gapper’s view, ironically, is that the entity that more or less pushed the check system, The Fed, should now be the organization to lead the US into the promised land of bank and payments innovation by designing and then managing the UK equivalent here in the US. (The Fed has released a working paper on their vision for a faster payments network and you can read it here.)

Maybe because the Fed will soon need something else to do.

Check usage in the US is seriously nose-diving. Sure, we still use checks here, but according to the Fed, in 2000 checks were used in about 40 billion transactions, in 2012, that number was reduced by 50 percent to 20 billion, at the same time the economy grew. Checks represent 7 percent of transactions by number of transactions on the retail payments side, as compared to cash (40 percent) credit (17 percent), debit (25 percent) and electronic (7 percent). And Americans say it is their least favorite payments method.

The demise of the check on the consumer side has come at the hands of that US innovation called the debit card that enable easy use of DDA funds to buy stuff in stores without the friction of writing a check (ok, truth be told, the debit card was invented in the US but it took off more quickly over the pond). Bank-driven innovation such as clearXchange and third party innovators such as PayPal, Square Cash and Google all provide digital alternatives to sending checks (or using cash) using email and mobile phone numbers – sounds pretty innovative to me! And an awful lot like Paym, the highly popular mobile P2P solution which launched in the UK just this year using a similar funds transfer scheme.

It’s true though that on the corporate side, something like 70 percent of all payments between businesses are still made by check. But that’s for one big reason: the alternatives haven’t, until recently, been all that compelling for buyers or suppliers.

Suppliers have pushed back on many of the paper check alternatives as too expensive to adopt or too hard to enable, and in many B2B transactions suppliers have a lot of power to call the shots. Buyers, well they just want their stuff. But there’s a visible shift now away from checks to digital payments between businesses thanks to the efforts of innovators like PayPal, NvoicePay, Intuit, Ariba and Dwolla who all offer plausible alternatives to paper checks that make it easy and cost effective for SMB buyers and suppliers to transact digitally. As for the big B2B’s; they move money between bank accounts digitally and have for ages.

Gapper also mentions as further proof of the waywardness of the US payments system the near ubiquitous use of Chip and Pin cards in the UK. Using the adoption of a technology that’s nearly thirty years old, that puts a chip in a plastic card and that was invented in the first place because Europe didn’t invest telecomm innovation a couple of decades ago to tout the innovativeness of the UK payments system is pretty nuts if you ask me. (Pardon me while I grab my Walkman and put a cassette tape in my cassette player – all wonderful innovations from twenty years ago that have, thankfully, died.) Seriously now, in 2014 does anyone think it’s innovative to put a chip with the relative brain size of a gnat in a plastic card and that we should standardize on that because that’s what they use in France?

Sure, it may be the case that the EMV train is barreling its way to the US but not because it’s an innovative way to solve the fraud problem at the in store point of sale. (Not to rain on anyone’s EMV parade here, but it’s probably also worth mentioning that the UK Cards Association released a report that said that card fraud in the UK, overall, is up 7.4 percent for every £100 of spend. Figures released by the UK’s Fraud Financial Institute reflect an increase of 16 percent in counterfeit fraud in the UK between 2011 and 2012 with fraud online up 11 percent and in store retail fraud up 26 percent.)If we were really committed to delivering innovation at the point of sale, that also delivered a secure solution, then we’d be investing in solutions that leveraged the cloud, the mobile device and new POS technologies to leapfrog plastic cards and EMV completely—delivering a truly innovative way of protecting cardholder data.

Oh wait, that’s right. We are.

Tokenization and end-to-end encryption are all available now, thanks to the efforts of innovators here in the US who have been clued in to the need to protect data when transacting online for nearly two decades – the exact place that fraud travels when EMV is implemented. Increasingly, thanks to mobile devices, online environments now include the use of mobile phones to transact at the physical point of sale. Third party innovators like Braintree and Bluefin are but two of the innovators who are enabling secure online and mobile transacting by rendering data useless to the cybercrooks.

Tokenization is making it possible for many mobile payments schemes to actually ignite, e.g. PayPal and LevelUp. And the oldest banking consortia in the US that handles about half of the transactions that run across the ACH network today, The Clearing House, has developed and is piloting a “dynamic credentialing solution” that will leverage its Secure Cloud technology to tokenize data and pass randomly-generated numbers, or tokens, during transactions.

Imagine that.

Gapper also mentioned the adoption of contactless cards is further proof of how far ahead the UK is in payments innovation. This is, no doubt, in response to the ongoing drumbeat of positive PR about the adoption of contactless cards by the Brits and the massive amounts of Kool-Aid being served to the press on that topic. In fact, a recent press release issued by the UK Card Association says that “monthly contactless card spend tops £100 million as transactions triple in a year.”

Sounds pretty compelling. Until you do the math.

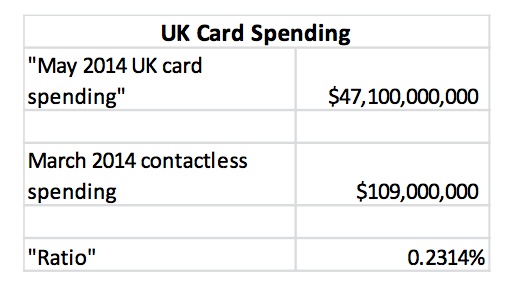

As a percent of overall spend, the spend that is being put on contactless cards isn’t even 1 percent, it’s more like 0.23—so less even than one quarter of one percent (See chart to the left which summarizes data from The UK Card Association that says that UK consumers spent $47.1 billion in May on goods and services overall on credit and debit cards and $109 million via contactless cards).

As a percent of overall spend, the spend that is being put on contactless cards isn’t even 1 percent, it’s more like 0.23—so less even than one quarter of one percent (See chart to the left which summarizes data from The UK Card Association that says that UK consumers spent $47.1 billion in May on goods and services overall on credit and debit cards and $109 million via contactless cards).

And the tripling of transactions? The percent increase year over year is actually something like from almost nothing—less than a tenth of one percent—to a bit more than nothing—one quarter of one percent. The average transaction amount is £6 – which is probably concentrated heavily on transit. This, of course, is after years of investment on the part of the payments networks to deploy contactless terminals and issue contactless cards. Reports in 2011 cited the “tipping point” for contactless was to be in 2012. It appears that UK consumers haven’t quite gotten the memo. By the way, did I mention that sticking chips with a brain the size of a gnat into a piece of plastic just doesn’t get my innovation juices going?

Just to give this a little perspective, Starbucks mobile volume on a monthly basis is something in the neighborhood of $139M, assuming that reports that their mobile app volume of 11 percent are accurate and using its latest reported sales figures.

Now none of this is designed to beat up on the UK or innovation or the innovators in the UK. Monitise and its mobile banking platform has done an incredible job of enabling mobile banking not only in the UK but worldwide. Skrill has innovated remittances, Ukash and Zapp mobile payments. Paym looks like it will be a homerun, and a new mobile commerce player, YoYo looks like it has the potential be pretty disruptive with, OMG, the QR code. All are but a few of the great things that the UK has spawned and which will or have the potential to change payments and commerce.

It’s unfortunate though that the banks here in the US routinely get hammered up one side and down the other for being big innovator sticks-in-the-mud, especially since the financial crisis of 2008. The banks have actually held their own in some pretty important areas where innovation really makes a difference and solves some real problems for consumers. Take online banking, mobile banking, digital P2P – all innovations that banks developed here in the US, delivered and kept secure; innovations that consumers actually use.

Ironically, Gapper’s piece was published two days before a report was issued by the British Banking Association describing the slowness of the UK banking system to embrace digital technologies in the areas of mobile banking in order to enable better customer service – something that the banks seem to really need judging by the low level of satisfaction that UK consumers have with their banks.

With respect to mobile payments, well, it seems like we’re doing a pretty good job of getting that flywheel cranked with innovation that works for all consumers with smartphones, not just those with handsets that have NFC chips in them. The innovators here in the US have seen from the efforts across the pond that having NFC available and getting consumers interested in using it are two entirely different things. And, let’s not forget how Square launched the mPOS market and hundreds of competitors all over the world – including those mentioned in Gapper’s piece, and how Starbucks showed the world that mobile payments and bar codes could be a winning combination.

It’s also true that there are a bunch of differences in the US and UK banking systems that to the uninformed might make it seem like we’re a bunch of duffuses when it comes to the digital transfer of money between bank accounts. I’ll mention that it’s a whole lot easier to get things done when you’re basically on one small island, with a fifth of the population of the US, where almost all of the economic activity is in one city, and where there’s a handful of banks.

But, here’s my big problem. I don’t get anyone claiming the government anywhere is who we should be looking to for innovations in payments, including our every own Fed. The government didn’t invent a single one of the innovative payment systems that have revolutionized payments around the world. Not the payment card which has help make payments electronic and provide an essentially global method of payment; not the ATM machine; not the incredible mobile money schemes that are providing financial inclusion across Africa; not PayPal or another of the payment methods that enable digital commerce. Nope, the government is what has foisted cash on us and in the US at least, paper checks.

I love reading John Gapper’s stuff and agree with most of the things that he writes about. He’s an amazing and well respected journalist and always has an interesting point of view to share. On this one though, I have to say that he just got it wrong.

But, hey, at least he didn’t advocate that we dump the existing system and all start using bitcoins.