Getting consumers hooked on something new is every innovator’s dream. There’s only one big problem: Consumers don’t break old habits easily.

Psychologists say that consumers are just hard-wired to resist change, believing that whatever they’re doing today is vastly better than any value they could get from making the switch to something new. And, as consumers, we’ve all exhibited that behavior ourselves, whether it’s always ordering the same entrée at your favorite restaurant (that’s me) or buying the same brand of car (my father). Said simply, we all sort of prefer the devil we know to the devil we don’t.

In payments, we’ve been watching different versions of this movie now for years and we’ve seen how they all end. Not enough consumers are willing to break their old payments habits to convince enough merchants that it’s worth investing in “the something new.” The feedback loop of consumers and merchants and more consumers and more merchants never takes hold.

Years and millions of dollars (and manyears) later, innovators (and their investors) eventually pull the plug.

We saw this happen just last week when Facebook decided to shutter Gifts. Gifts seemed like such a logical idea at the time: make it easy to send a gift to a friend on their birthday. They did that by putting a nice little prompt right at the same spot where the “Happy Birthday” greeting could be entered. Easy peasy.

Except if you were the recipient.

Recipients got plastic Facebook giftcards that were mailed to them. Each gift card could hold separate balances for any merchant participating in the Facebook Gifts program, thus preserving exclusivity for merchants but (in my opinion) confusing the heck out of the recipient. Let’s say a lucky birthday girl has four generous friends all of whom sent her an e-gift via Facebook Gifts on her birthday. She gets one Facebook card that holds the different balances from those four different friends and the merchants they each chose. Facebook thought that one card would be more convenient than getting four, except that was asking consumers to change how they used gift cards at stores. Apparently not enough of them liked it well enough to get merchants to sign on and/or the merchants that were part of the initial batch interested enough to stick with it. So Facebook killed it last week.

Getting consumers hooked on new things is the subject of a really interesting book called, appropriately, Hooked. Nir Eyal is the author and he’s an entrepreneur and a lecturer at Stanford Business School. Hooked offers a methodology for getting consumers to love something enough to make it a habit, which is, of course, the zillion dollar question now up for grabs in payments and commerce. Everyone in payments is focused on getting consumers interested in ditching whatever they are using today for something “better”: a digital wallet, a mobile coupon, a prepaid card, a new loyalty program, a new app, whatever.

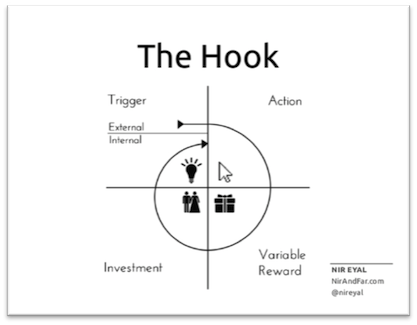

Hooked’s thesis has four major components: The Trigger, The Action, The Reward and The Investment that all need to be managed to form the habits that will hook consumers.

Triggers sort of start it all by prompting a user to do something. Triggers can be external (e.g. ads, share and like buttons, seeing a store) or internal (e.g. emotions, people, situations, routines).

Actions are what people do in response to a trigger – but with two big exceptions. Eyal says that the user must be both motivated (they get a reward) and able to take an action (the action has to be simple, not cost a ton of money, not take a lot of time, not be too mentally taxing, etc.).

Rewards are the payoff for taking the action and are the incentive for taking an action. Rewards don’t always have to be about money, even though they often are. Tribal rewards are more social (e.g. getting a response from your friends when you post on Facebook or Instagram), Hunt rewards are the payoff from a search for resources (e.g. finding something on Pinterest or Houzz) and Self rewards are about mastery (e.g. my inevitable quest to beat my own personal best score in BeJeweled or Skeeball).

So far, this isn’t really rocket science and sounds pretty similar to the concepts that Charles Duhigg, one of our IP 2014 keynote speakers, documents in his book, The Power of Habit, which I’ve discussed before What makes Hooked slightly different, though, is Eyal’s concept of “investment” and the role that it plays in completing “The Hook” that Eyal claims ultimately creates the habit.

“Scratching the itch” that Eyal says triggers can create only happen if the rewards that people get from scratching that itch leaves them wanting more. That’s the notion of Investment, which Eyal says gives consumers a reason to “load the next trigger.” Eyal describes this as banking a “store of value” that makes what the consumer does more valuable in the future. It talks about the psychology of frequent flyer programs, points-based reward schemes and even TV show cliffhangers (raise your hands if you aren’t chomping at the bit for the next season of Scandal or Homeland to start). It’s why the “gamification” of rewards is such a popular concept.

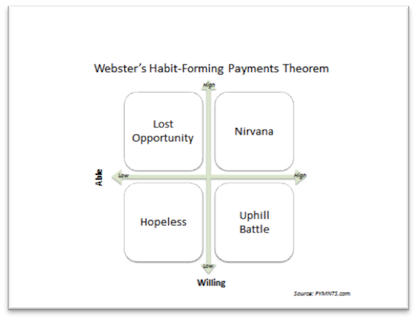

So what’s the shortest path to producing the habit-forming behavior that every payments innovation is seeking? I’d like to introduce you to Webster’s Habit-Forming Payments Theorem ☺.

If the two big variables that really determine whether people form a habit–or get hooked–is whether they can (are able) and want to (are motivated). If so, then highly motivated, highly able consumers are, therefore, the innovator’s ultimate prize.

Disengaged consumers who aren’t able to respond to a trigger are the innovator’s booby prize with tons of money wasted on people who are neither interested nor able to respond.

So what’s the best way to position an innovation to win the ultimate prize?

Here’s where Webster’s Habit-Forming Theorem might help. The x-axis measures ability and the y-axis measures willingness – both from the consumer’s point of view. An innovation that has lots of willing consumers with no ability to use that innovation is a lost opportunity. Lots of ability to use an innovation without willing consumers is an uphill battle. At a minimum, this simple 2 x 2 matrix could help innovators decide in the privacy of their own innovation labs (or garages or whatever) where their innovation really fits, and where they think their competition’s does, too.

Now, let’s put the Webster Theorem to the test.

Take open loop prepaid cards.

These products have been around for something like 13 years. These mag stripe plastic cards that are accepted in all card-accepting merchant locations on- and off-line, have been marketed as an essential tool for the unbanked and a product that will bring financial inclusion to the millions and millions of people in the world who live outside of the financial mainstream. There’s just one problem: they’ve struggled to ignite. The very consumers for whom these products were developed haven’t developed the habit of using them.

In fact, consumers who have them (perhaps their employers deposit their paychecks on them) exhibit the following behavior: paycheck gets deposited on card, consumer goes to cash machine and then withdraws most of the money in cash. Unbanked consumers aren’t necessarily showing up at stores in droves to buy open loop prepaid products off of J-hooks. Those who are more of the “unhappily banked” consumers who are using products like Walmart’s Bluebird that looks and acts like the bank account that they’ve always had (minus the high bank fees). The unbanked are generally unwilling to ditch the tangible cash product for which they pay no fees for an intangible plastic product that costs money to use. So the consumers for whom these products were intended are clearly able, but they are not willing to use them. This puts prepaid cards in the “uphill battle” quadrant, according to Webster’s Theorem.

Lots of innovators are trying very hard to move up the matrix to “nirvana” by adding features that make keeping funds on a plastic card more appealing:offers, short term loans and the like. The mobile device, which can make the intangibility of the prepaid product more real by providing balance and transaction information, is also useful in addressing the issues associated with the intangibility of knowing exactly how much money is available to spend. But unless the utility and economics of the product change, the uphill battle will continue since the only habit that prepaid products have successfully nurtured is a continued use of cash.

Let’s take another example, which is my all-time favorite: NFC.

In the U.S., NFC started out in the hopeless quadrant–no willing consumers and no real places to use NFC cards (or phones). Where consumers could use cards or phones, in the UK, for example, consumers didn’t seem all that interested. Now, all of you reading this are pretty sophisticated people who understand how NFC works because it’s your business. But ask Joe Six-Pack what he thinks of NFC. The ones I’ve asked worry that phones enabled with NFC will randomly interact with POS terminals and drain their bank accounts. You laugh. But the consumer perception is that “tap and go” payments takes too much control out of their hands and puts it with a technology that they don’t understand. Even the Brits who have been living with NFC for years say they’d rather have biometrics. Depending on your point of view, NFC either remains in the hopeless category or has moved to the “uphill battle” quadrant. But for both spots, it has its work cut out for it to develop into a habit-forming experience for consumers and, therefore, a technology that merchants are willing to invest in.

Yes, I know what you’re saying: Apple’s new iPhone will have NFC and then you’ll be eating humble pie! As I said last week, you’ll have to wait a couple more weeks for my perspective on Apple and NFC, but I have yet to see Apple put a product in market that’s either a hopeless or uphill battle for them and the consumers they serve.

Let’s give the Webster’s Theorem another workout, this time on mobile wallets.

For the moment, let’s set aside the fact that “mobile wallets” are still evolving as a concept and the definition of the term is anything but consistent. Let’s take two examples: apps that consumers download on their phones for the purpose of paying in a physical store; and apps that consumers download for other purposes that are also payment-enabled.

To be successful, mobile payment apps have to get consumers to use them with enough frequency to develop into a habit-forming experience. The Starbucks mobile app success is because the coffee chain layered an easy payment option on top of two other ingrained consumer habits: buying coffee at least once a day and using a Starbucks prepaid card to pay for it. Moving those smartphone-toting consumers to a QR code mobile app that every single one of them could use on Day One has driven something like 15 percent of Starbucks volume in fewer than 3 years. Willing and able consumers delivered Starbucks’ “nirvana” mobile app experience.

Building the frequency that delivers habituation is also why so many innovators turn to the QSR space to launch mobile apps and do it with QR codes. Breakfast and lunch daily plus the convenience of the mobile phone to pay is the combo platter served up in this environment. Innovators like LevelUp have made it worthwhile for consumers to download and use the app by offering rewards that pay off with more frequent usage. And that makes the investment in continuing to use LevelUp more valuable. A QR code-based payment method also enables payment across all phones and all merchants cost effectively and it also taps into behavior that consumers are familiar with in other mobile app settings. Consumers have been using mobile boarding passes and mobile coupons with QR codes for years. They like using them and know how to use them. Willing consumers and able consumers in this mobile payments scenario, again, deliver “nirvana.” BTW, once you get a critical mass of willing and able consumers into “nirvana,” scale becomes a whole lot easier to achieve (still hard, but at least there’s something to leverage to keep the flywheel spinning).

People also download mobile apps for other reasons, e.g. Uber for taxis and a myriad of others for online ordering. Many payments innovators are attaching payments to those apps in order to build habituation and frequency. That is exactly what Chinese internet giants Alipay and TenCent are doing in an effort to expand the use of those digital accounts outside of their own walled gardens. Like Starbucks, they are embedding payments into high-frequency, high-utility mobile apps to build habituation and preference and therefore achieve “nirvana.”

But here’s where I think using Webster’s Theorem to examine the various players across the mobile payments landscape could get interesting and even a bit cautionary.

The worst place on the matrix to be is where consumers are neither willing nor able for any reason to use a payments product. Yet it’s amazing how that doesn’t seem to stop innovators from spending time and money trying to solve the toughest and most expensive problem in payments. I remember asking Square’s co-founder, Jim McKelvey, what advice he’d give to an innovator wanting to solve these two-sided problems in payments. He answered in one word: “Don’t.”

Most innovators today operate in the “uphill battle” mode where vast fortunes are being spent trying to convince consumers to willingly switch away from what they do today to something new that they might have enabled at a few places to seed the market. The uphill battle is convincing enough consumers to make the investment in the longer term, when the longer term isn’t readily apparent to consumers nor appealing enough today to ask them to patiently wait. Not having enough interested consumers isn’t a glowing advertisement for getting merchants to sign on. That’s what I believe happened to Square’s wallet. There were not enough consumers who could use it in enough places to matter to them. Those handful of consumers lost interest as did present and future merchants. I predict that we will see the taps slowly being turned off of many of these “uphill battle” innovations over the next year or so as investors figure out that getting consumers to change their habits is but a short hop to hopeless (and much smaller bank accounts).

The tragedy of payments, though, I think will happen where it’s too hard for willing consumers to use a particular payments innovation often enough to get hooked and in enough of the places that matter to them. In the digital payments world, that’s the slippery slope that those with a digital consumer base already in the habit of using the product must avoid. If you think about it, the difference between a lost opportunity and uphill battle is the ability for consumers to easily adopt a new payments habit. This is something that will give willing consumers places to perfect their habits and disinterested consumers an incentive to take the first step to habit-forming behavior. Innovators that do that by introducing the fewest moving parts will win. It’s why I think that success in the mobile/digital payments world will ultimately leverage in some way the digital habits that consumers have perfected over the years, such as downloading apps, pushing the buy button online, typing in a PIN at checkout, using QR codes, etc. And that may not be as crazy as it sounds because the most momentum we’ve seen in mobile payments leverage some combination of those user experiences.

Where you see some of your favorite innovations in payments fitting onto Webster’s Theorem?