REPORT: What Apple Pay At Five Says About The Future Of Mobile POS Payments

Apple Pay went live five years ago yesterday, on Oct. 20, 2014.

When Tim Cook took the stage a month beforehand to announce this mobile payments innovation, he shared Apple’s vision for modernizing how consumers and merchants would interact at the physical point of sale. Instead of wasting time fumbling around for plastic cards and swiping them at terminals, consumers would use the mobile devices always in their hands to check out quickly, easily and securely with Apple Pay’s mobile wallet.

He used this video to make that point.

In true Apple fashion, the user interface was clean, crisp and slick. Apple Pay’s security and privacy protocols were state-of-the-art, leveraging the NFC standard and their Secure Element to enable secure, tokenized, contactless payments at the physical POS. Issuers lined up to enable cards in their wallets.

The tech press and pundits lauded Apple Pay as a payments and commerce game-changer, and predicted the demise of the plastic card a decade hence. Some even said Apple Pay would replace PayPal – and investors took note. eBay, which owned PayPal at the time, saw its stock slide 6 percent the day Apple Pay was announced.

I wasn’t so sure.

As I wrote in a piece right after Apple Pay was unveiled, I thought it faced many difficulties in securing ignition, and the company had vastly underestimated the challenge of getting consumers to adopt it. Apple’s reputation as a mobile innovator couldn’t overcome the reality of launching with very few merchants with contactless terminals – and even fewer consumers with compatible phones.

Perhaps the biggest obstacle of all was the consumer’s muscle memory associated with using cards in stores to pay, and their ubiquitous penetration. The lowly plastic card – practically a prehistoric relic standing alongside an iPhone 6 and an Apple Pay wallet – was accepted everywhere and at every merchant point of sale. Most consumers had a debit, credit or prepaid card they could use, and knew it would work the same way each and every time. Apple Pay wasn’t anywhere close to being able to make that claim.

And contrary to the video, most people weren’t fumbling for cards (they used them all the time). In fact, they could pay with cards lickety-split. For most consumers, there was no burning problem to be solved at the physical point of sale.

Five years later, there are more consumers with iPhones and Apple Pay wallets and more stores that can enable an Apple Pay transaction. So that’s not a problem anymore.

So, there are more transactions, because there are more phones and more places to use it, but the rate of use – the percentage of people who can use Apple Pay and do at the physical point of sale – has remained small and steady.

Apple Pay at Five

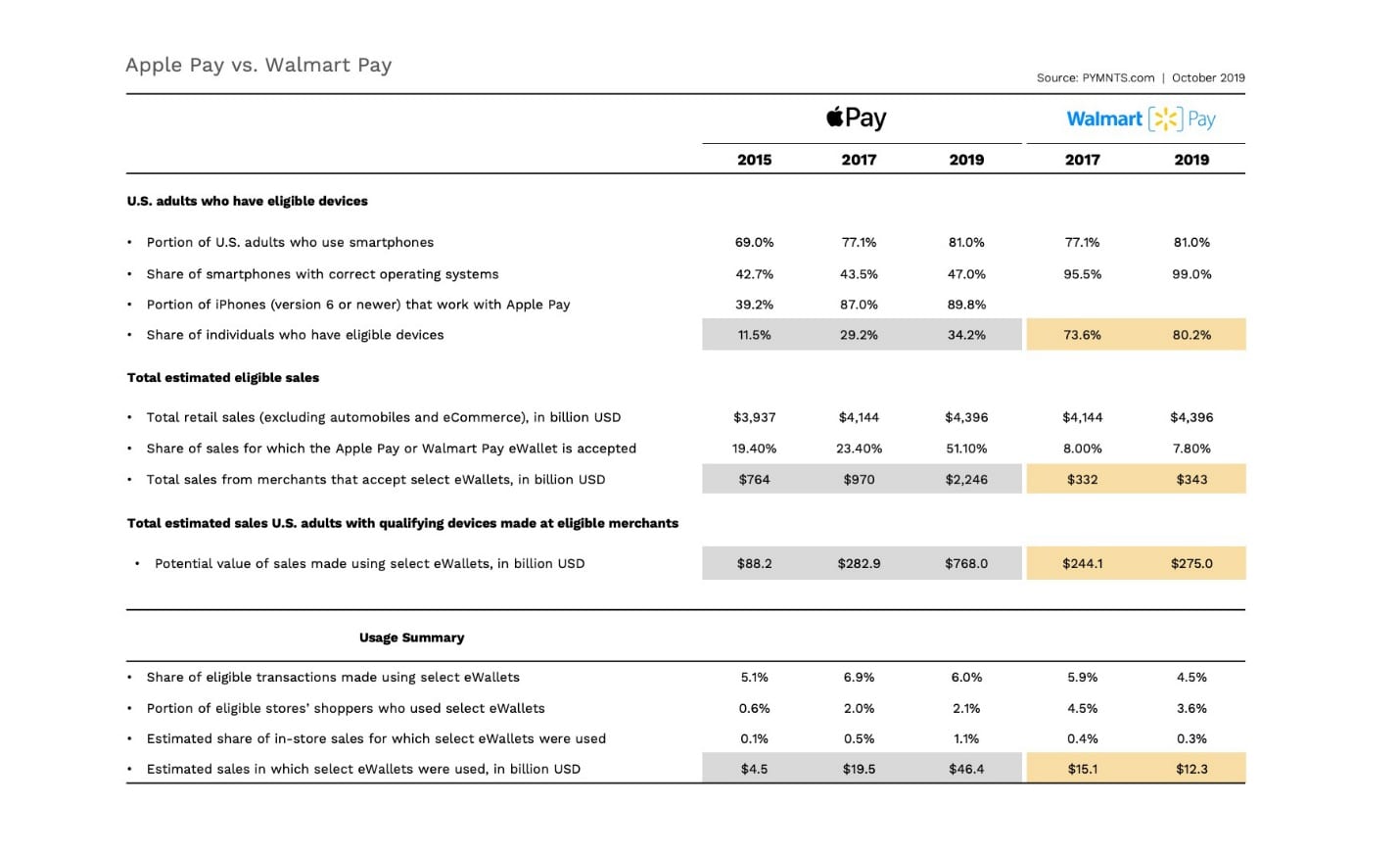

At the time of iPhone’s live debut in October of 2014, merchants accounting for only 19 percent of all retail sales could enable an Apple Pay transaction, only 39 percent of all iPhones could support an Apple Pay wallet and just 11 percent of all consumers owned one. Getting to critical mass would come down to solving the age-old “chicken and egg” platform ignition problem: getting enough consumers with the right iPhones to use it at stores that accepted it, which would incent more merchants to get on board, which would get more consumers to use it – and so on.

PYMNTS decided to document Apple Pay’s adoption and usage at the physical point of sale as almost a real-time case study in igniting an entirely new way to pay in stores where plastic cards had ruled for 60 years. Shortly after its launch and for its first three years, we studied U.S. consumers with the right iPhones who shopped at the stores that accepted Apple Pay each quarter to document how many of them used it to check out. Over those years, Apple never released anything other than vague statements proclaiming Apple Pay’s “awesome” progress, so our studies became the de facto public record for its in-store performance.

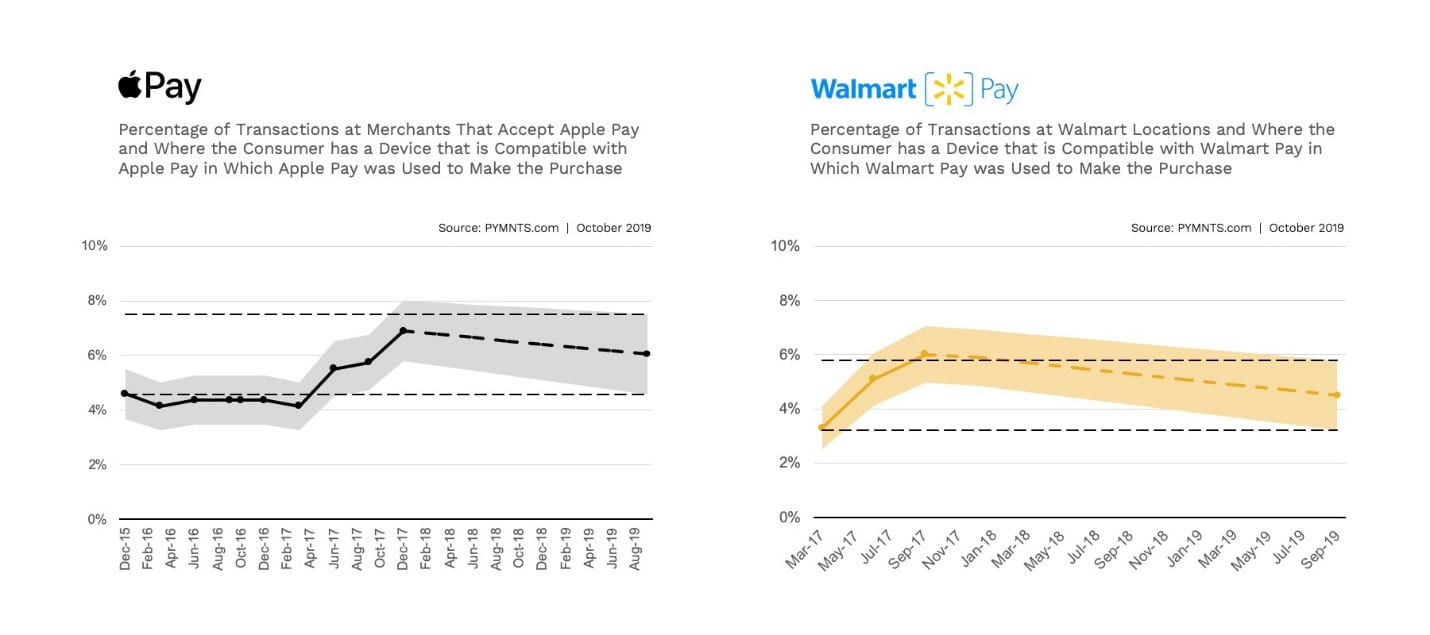

Over that three-year period, we reported that, not unsurprisingly, adoption and usage – the percentage of people with Apple Pay who shopped at merchants with contactless terminals and used it to pay at those merchants – was a slog.

Like many of you, I would stand in line behind people, iPhones in one hand and plastic card in another, paying for their purchases in the store. For most consumers, ubiquity, certainty and familiarity with how to pay trumped slickness and elegance, for both mobile and digital.

Our survey data backed that up.

I wrote over those years that the longer it would take for those consumers to get comfortable and try Apple Pay once, and then twice, at stores that supported contactless transactions, the greater the risk that it would never get enough usage and critical mass to overtake cards at the physical point of sale.

Five years after Apple Pay was available for consumers to use, and two years after our last consumer field study, PYMNTS went back into the field to examine iPhone owners and their usage of Apple Pay at the physical point of sale at merchants that accepted it.

Like always, we asked eligible consumers – those with iPhones with the Apple Pay wallet who made a purchase at a store that could enable an Apple Pay transaction – whether they used Apple Pay to pay for those purchases. For this study, in September of 2019, we fielded a national survey of 1,000 such consumers.

Apple Pay’s Payments Pie Problem

As I mentioned earlier, the Apple Pay opportunity pie has grown tremendously over the last five years, because the number of iPhones that can use Apple Pay and the number of merchants that can take it have both increased several-fold.

According to the PYMNTS analysis, in 2015, about 69 percent of the total U.S. adult population had a smartphone; currently, 81 percent own one.

In 2015, Apple Pay was compatible with only two iPhone models, iPhone 6 and 6S, representing about 39 percent of all iPhones with 11 percent of consumers having one. Today, that percentage has grown to roughly 89 percent of all iPhones and about 34 percent of all consumers capable of using Apple Pay to pay for an in-store purchase.

Apple has also done a lot of nudging over the last few years to prompt consumers to download Apple Pay. Upgrading the OS, for example, isn’t deemed complete by Apple until Apple Pay is installed – and it’s also required to make that little round, red circle on the Settings app on the iPhone home screen go away.

In 2015, contactless terminals were new to merchants, and merchants that offered contactless only accounted for roughly 19 percent of all retail sales. Many merchants with contactless terminals also resisted activating contactless for fear of losing control of their customers and competition for their own mobile wallets. In 2019, contactless terminals are present at merchants that we estimate account for 51 percent of all retail sales, excluding automobiles.

As a result of the increase in the number of compatible iPhones and in merchants that take contactless, the volume of transactions that could be paid for with Apple Pay has increased more than eight-fold, from roughly $88 billion in 2015 to $768 billion in 2019.

In 2015, when Apple Pay was a newbie, consumer usage was about 5.1 percent. In other words, among consumers who could use Apple Pay to pay in a store that accepted it, they did so only one out of every 20 times. Just to be extra clear: When we measure usage, we are referring to consumers with an iPhone capable of having an Apple Pay wallet who are shopping in stores capable of enabling an Apple Pay purchase.

Five years later, usage of Apple Pay to check out in a physical store is about 6 percent, down from 6.9 percent in 2017. In other words, roughly 1.2 out of every 20 people who could use Apple Pay to pay in a store that accepts it, do so.

Based on these results, we estimate that Apple Pay accounts for roughly 1.1 percent of all retail and food services sales – excluding online and auto. Unless the usage rate increases from this 1/20 range, there are only two paths to increasing Apple’s share of the payments pie at the retail point of sale.

First, and most promising, the penetration of contactless terminals could increase (it could almost double from 51% percent to 100 percent, eventually). Second, and less likely, Apple’s share of smartphones could increase. Neither provides much headroom for growth in the long term, and even less so in the next few years.

The Walmart Pay Payments Pie

As part of our analysis in September, using the same methodology, we also surveyed 1,000 smartphone owners about their adoption and usage of Walmart Pay.

Walmart Pay launched a year later than Apple Pay, in December of 2015, but without two of the ignition hurdles facing Apple Pay.

Walmart Pay was enabled at all of Walmart’s U.S. stores, making the wallet ubiquitous from the start. Walmart Pay was compatible with almost all devices, too. Consumers with just about every kind of smartphone, Android and iOS, could download the Walmart Pay app – 95 percent of all smartphone users compared to Apple’s 39 percent – and could use it at every single Walmart store.

That meant Walmart Pay’s ignition challenge was to create the incentives to get consumers to download and use the Walmart Pay app to check out instead of use cash or cards in the store.

When Walmart Pay launched, it was described as a “hands-free” way to pay without tapping or waving a phone at the terminal – appealing to busy moms with kids in tow who didn’t want to fumble around for cards or fiddle with a phone at checkout. The Walmart Pay app was also linked to its Savings Catcher feature – something that was once touted as a key value driver for Walmart Pay – which did automatic price comparisons and deposited the savings differences into an account that consumers could apply at checkout via the app.

For the first three years of Walmart Pay’s debut, we saw impressive, almost hockey-stick, growth. In its first two years, the adoption and usage of Walmart Pay had outpaced that of Apple Pay, and in less time.

But unlike Apple Pay, over that last two years, Walmart’s piece of the payments pie hasn’t seen that much of an increase. In the U.S., Walmart Pay’s retail footprint includes Walmart stores – and, since all stores could enable it almost from day one, growth in share of sales had to come from growth in Walmart’s in-store sales.

Overall smartphone ownership has also increased since that time, but since Walmart Pay has always been accessible on more smartphones than Apple Pay, the growth in ownership hasn’t expanded its eligible consumer base all that much.

And over that same period, in November of 2018, Walmart announced changes to its Savings Catcher program – and announced that it would sunset the program in May of 2019. And Walmart has invested heavily in online order-ahead and curbside pickup for groceries, which drives more than half of their U.S. retail sales.

Today, Walmart Pay is positioned as a fast, easy and secure way to pay in Walmart stores.

Over the last two years, we observed that Walmart Pay’s in-store usage has declined slightly, among those consumers who have phones that can enable Walmart Pay and who choose to use it at the physical point of sale – although it’s close enough statistically to be more of a flat line than a pronounced downward trend. We estimate that Walmart Pay accounts for about 3.6 percent of sales in the retailer’s physical stores.

Like Apple Pay, Walmart Pay’s use as an in-store payment method among consumers who could use it seems to have plateaued. Unlike Apple Pay, that could be the result of consumers using the Walmart Pay app to order ahead and pay for groceries instead of going to the physical store to shop for them. Or, like Apple Pay, it could mean consumers don’t have a problem using whatever other form factors they have always used to pay.

The Digital Wallet Achilles Heel

Over the last five years, I’ve been very vocal on these pages about the failure of Apple Pay – and most every other digital wallet – in displacing the plastic card at the physical point of sale. Apple Pay and Walmart Pay, for different reasons, today stand as interesting proof points about the power of consumer habit, the efficiency of using plastic cards, and the incentives required to change the behavior of consumers when most of them don’t feel they have any problem using cards to pay when they go into stores to shop.

Long gone, thank goodness, are the annoying chirps and screams that came from terminals in the early days of chip and PIN transactions. These days, those transactions are quick, easy and quiet. More issuers are also putting contactless cards into the hands of consumers who, according to our research, are more than eager to use them to pay in-store.

In the 2019 How We Will Pay study released last month, which looked at more than 5,000 U.S. consumers, interest in contactless cards increased by 20 percent over the last year, now including nearly one-third of all consumers. Forty-three percent of the mobile-first 30- to 40-year-old bridge millennials cite having an interest in and willingness to use them at the physical point of sale. Convenience (77 percent) and security (61.9 percent) were noted as the key reasons. When it comes to where consumers are interested in using contactless, mass merchants (81 percent), grocery stores (80 percent) and drug stores (76 percent) topped the list.

Those are the same everyday merchants that Apple Pay targeted when it launched.

In a world dominated by mobile devices and apps – and trillions of dollars of sales conducted at the physical point of sale – cards still rule.

The Plastic Card Tail That Wags the Mobile Wallet Dog

This insight has not gone unnoticed by Apple, Walmart or even PayPal with Venmo, as digital wallets are turning to them, quite ironically, to drive usage of their digital wallets.

As I noted above, Apple Pay has only a few levers at its disposal to drive more share of Apple Pay at the physical point of sale.

With more than 80 percent of the U.S. adult population owning a smartphone and all of Walmart stores capable of enabling a Walmart Pay transaction, Walmart Pay gives more consumers more of a reason to download and use it.

Say hello to the plastic card with cashback rewards.

Apple made news when it introduced what Goldman Sachs’ CEO said was the most successful card launch in history – the Apple Card – which offers 2 percent cash back on Apple Pay purchases. The Apple Card runs over Mastercard rails, so it can be used everywhere Mastercard is accepted – including all of those physical points of sale that Apple Pay set out to disrupt five years ago.

Walmart introduced a cashback credit card, too, issued by Capital One and also running over Mastercard rails, which offers the same thing for Walmart Pay users. For Walmart, the co-branded card is also a way to capitalize on purchases made beyond its physical store footprint.

PayPal also joined the digital wallet credit card game when it announced last week that it will issue a Venmo credit card next year, designed to monetize the 40 million users of its digital app.

Now, whether these cards become the bridges to getting consumers to use digital wallets instead of those cards at the physical point of sale remains to be seen.

For now, they seem to be an admission by the mobile payments pioneers that consumers have some pretty strong preferences for what they like to use when checking out in the physical store.

So, What Have We Learned?

Despite the splash and pizzazz of the various “Pays” at the physical point of sale over the last five years, the Starbucks mobile app remains the most successful example of a mobile wallet ever introduced in the U.S. Mobile app users now top 16 million, driving roughly 40 percent of sales, according to the Starbucks CEO during the company’s last earnings report.

What hooked consumers at first – the ability to pay in-store using an easy-to-reload mobile app and collect cool rewards – isn’t necessarily why consumers remain hooked today. Increasingly, the appeal of the Starbucks mobile app is the convenience of using it to order ahead and skip the checkout line completely, while racking up stars to redeem on future purchases.

For the Starbucks I visit today, the lines of people waiting to order and check out in the store are dwarfed by those who have already done that on their way there. The order-ahead feature is apparently so successful that Starbucks is piloting a mobile-only store in New York City.

Every QSR is investing in order-ahead to try and hook consumers into using their app. And delivery aggregators are using it to appeal to consumers who don’t want to go to a physical restaurant to eat.

It’s what every retailer with an online presence is prompting consumers to do – buy this dress or those shoes or that watch online and pick it up in the store. It’s why grocery stores, especially Walmart, are investing so heavily in curbside pickup. Why use an app to check out in the store when you can use it to order ahead and skip the standing-in-line scene entirely?

Maybe we’ve learned what we knew all along: that for a new platform to ignite – any platform, not just payments – it has to solve a big and obvious friction. For consumers, then and now, when they are in the store checking out, the majority of the time they reach for their cards and not their mobile phones.

When they do reach for their phones, it’s because they want to skip the instore experience completely. The biggest pain point when shopping in the store isn’t pulling out a card to pay at checkout, it’s hoping that what a consumer wants to buy is in the store and then waiting in line to pay for it if it is.