Does Amazon Plus Kohl’s Equal Retail’s Future?

Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet Robert Frost was famous for using rural country metaphors when examining important philosophical issues of the modern world.

Little known fact, perhaps, is that Frost was a man whose life straddled two of today’s most active centers of innovation. He was born in San Francisco and would spend his early childhood years there. After his father died, Frost moved with his family to Boston and remained there until his own death in 1963.

Frost penned many famous poems, including President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration poem in 1961, but perhaps none so relevant to the many innovators toiling away in the cities of his birth and death as “The Road Not Taken.”

Written in 1916, the poem memorializes the story of choice — in this case, the choice made by a traveler who had approached a fork in the woods and decided to take the road less traveled because it was “grassy and needed some wear.”

Critics have debated for decades the subtext of Frost’s poem: Was the traveler’s choice impulsive? Or was it made by an independent nonconformist with the confidence to overcome whatever unknowns he might encounter?

It’s also a decidedly fitting metaphor for the many choices retailers must make as they stand at a critical fork in their own roads: how to collaborate or compete with Amazon.

More and more large retail brands have taken the road that today seems a lot more traveled than it used to be: collaboration by way of creating storefronts on Amazon. In 2016, Gap CEO Art Peck said that he’d be “delusional” not to consider selling on Amazon — and he did. Nike and Amazon announced a partnership in June of 2017 to do the same, and Sears made news a month later when it decided to sell Alexa-powered Kenmore products via Amazon.com. These announcements follow moves made much earlier by brands such as Michael Kors, Gucci, Tory Burch, Vince, Kate Spade and Stuart Weitzman — just to name a few — to sell their products on Amazon, too.

It was the announcement last week of Kohl’s partnership with Amazon to use its physical store network to accept returns from Amazon customers that introduced a new twist to that choice at that retail fork in the road. That announcement followed news earlier in September that Amazon would create its own storefront inside Kohl’s physical stores to sell its line of Alexa-powered devices.

The partnership news started a chain of media reports describing Kohl’s decision as a “deal with the enemy” and the “wrecker of brick-and-mortar retail” by a player (meaning Kohl’s) down on its luck.

Kohl’s, like many of its mass merchandising cousins, has seen its stock price suffer as foot traffic and sales have declined dramatically over the last several years. Kohl’s stock hit a high of $79.07 in April of 2015. By June of 2015, it had lost more than half of its value, trading at $35.32. At the close of the market on Friday, Kohl’s stock was trading at $46.07 a share.

More interesting than its rise in stock price is how the market views Kohl’s choice to take a retail road much less traveled — and, from my perch, how it will redefine what it means to be an omnichannel retailer.

Are Retailers Ready for Omnicommerce?

Being “omnichannel” is important to every retailer. It’s why digital pure plays like Bonobos and Birchbox have opened brick-and-mortar storefronts and BarkBox is selling its boxes at Target. It’s also why physical retailers have invested heavily in “going digital” and creating mobile apps. And why Walmart acquired pure plays like Jet.com, Bonobos and Modcloth. The ability to meet consumers across all touchpoints they shop is what drives most retail agendas today, regardless of the channel in which the retailer first started. Distribution and reach is the name of the game.

We’ve been tracking the readiness of retailers to do just that — to be, what we call, “OmniReadi,” in collaboration with Vantiv — for more than two years. Each quarter, we examine more than 150 variables essential for delivering a seamless consumer shopping experience for more than 100 physical retail brands — department stores, specialty retail and mass merchandisers.

We’ve built a statistically rigorous model that takes that input and produces a benchmark score across all of those merchants, as well as specific retail segments. We weigh that scoring to reflect the portion of retail sales overall that each merchant represents and the statistical relevance of each variable in creating an optimal omnichannel experience.

What we’ve learned over that time is interesting and relevant, especially for the Amazon/Kohl’s team-up.

As important as the omnicommerce experience is for all retailers, most are a long way from delivering it. Not for lack of trying — since we have seen some progress at the margins — but in delivering on the variables that will pack the biggest punch for them and the consumers they serve.

Like any Index though, the story isn’t so much in the wild swings in the benchmark score itself. In fact, the swing between the first benchmark score of 63.5 and our last report of 67.6 was only 6.5 percent. The real stories are found inside sectors, categories and the variables that influence the omnireadi performance of individual merchants.

For instance, we’ve observed:

- a narrowing of the readiness gap between large and small merchants over the last 12 months, as even smaller retailers understand that remaining relevant means being omnireadi;

- an emphasis on readiness in the areas that help consumers feel more in control of information about their spending at those retailers, including access to their purchase history across channels, the need for price consistency across channels, and the ability to use coupons and promo codes across all channels; and

- an emphasis on solving for a few key points of friction for consumers, including the ability to return products bought online to a physical store and get refunds there, even if purchases were made using a digital wallet.

When Consumers Talk, Do Omnichannel Merchants Listen?

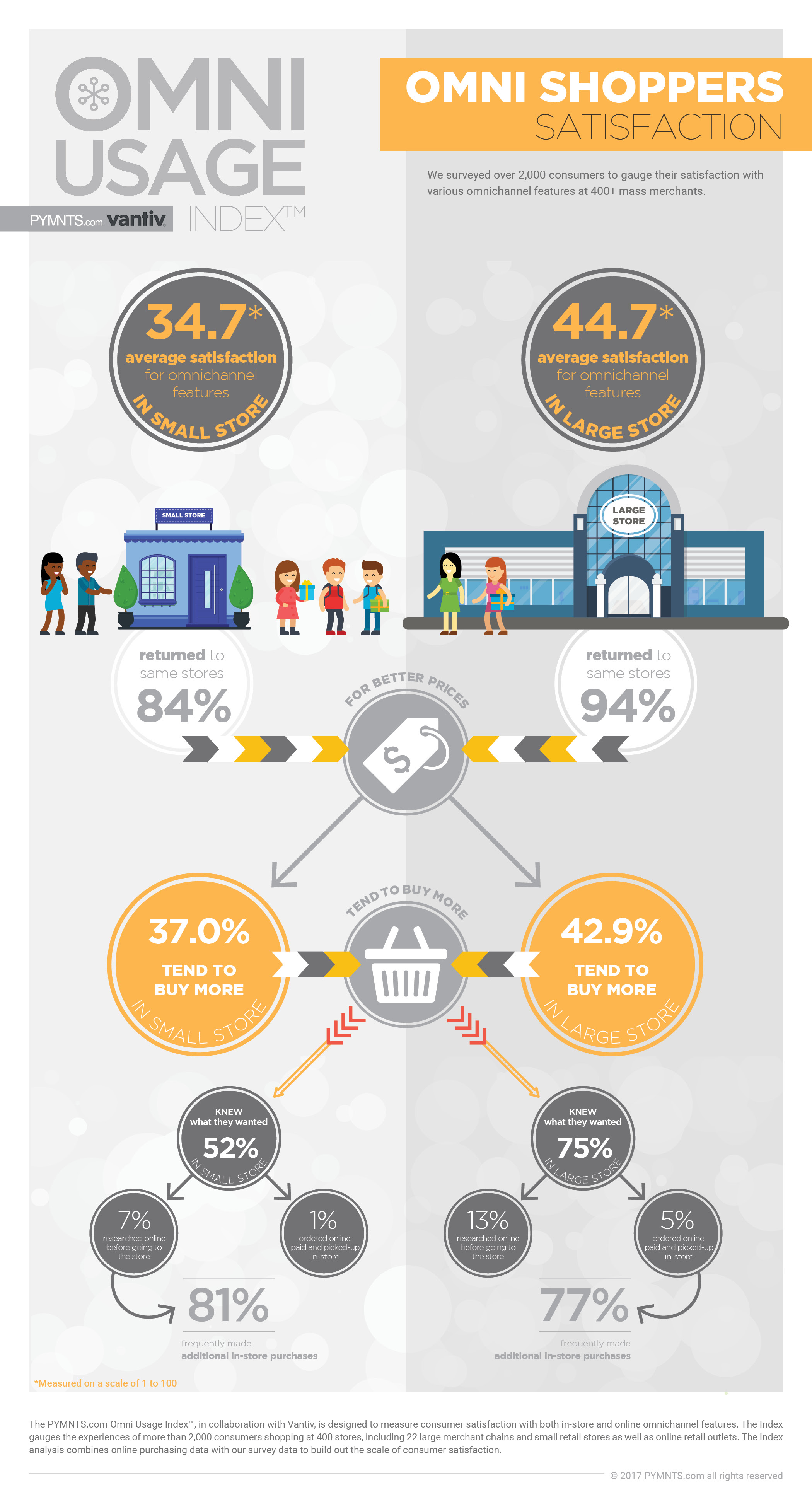

Last summer, we asked consumers to weigh in on their satisfaction with the “omnireadiness” of the merchants they shop. Two weeks ago, we released the results of this work: the OmniUsage Index.

There are more than 190,000 data points that went into creating the Omni Usage Index, including data that helped us identity three distinct shopper personas. I hope you will take a peek at all of them when you have a chance.

The OmniUsage Index was produced after asking 2,000 consumers who shopped at large retailers and 2,000 who shopped at smaller retailers to tell us about their shopping experience with each merchant. We did that while it was still fresh on their minds — the moment they left the store they shopped. For purposes of the study, smaller is somewhat relative, since we examined only mass merchandisers, department stores and large apparel chains. Even small in these categories can seem large when compared to the stores that line Main Street, U.S.A.

We asked consumers to tell us why they shopped that store, how often and why they do and to rate their level of satisfaction with the features and functions that represent a best-in-class omnicommerce experience with that merchant.

What we learned put a big punctuation mark at the end of physical retail’s well-documented challenges and reflected the potential wisdom of Kohl’s move to take that retail road less traveled — and Amazon for offering the option.

Let me tell you why.

Unhappy Creatures of Retail Habit

There’s really no other way to say it: Consumers aren’t satisfied with how retailers serve them at any of the touchpoints they shop: brick-and-mortar locations, mobile app or browser.

As we first reported in May, more than 80 percent of consumers find shopping in physical stores frustrating, unproductive and a waste of their time — despite shopping at physical stores more often and spending more of their money there.

We found consumers to be equal opportunity critics, though. In that same study, consumers report shopping online slightly less friction-filled — but with a bigger potential, consumers believe, to improve their overall shopping experience in the long term.

The OmniUsage study measured the relationship between the friction consumers say they experience and their satisfaction with the merchants they shop.

As you might expect, consumers have a higher level of satisfaction with larger retailers than their smaller counterparts — but with consumer satisfaction benchmarks at 44.7 and 34.7, respectively, having a higher level of satisfaction seems a bit relative.

The story when told by the characteristics of the shoppers — those who shop mostly online (16 percent of our sample) or those who shop in mostly brick-and-mortar retailers (36 percent) — isn’t much better.

For those who say that their primary interaction with that merchant is online, the consumer satisfaction benchmark is 42.2; for those who shop primarily at brick-and-mortar retailers, it’s 36.9.

The 49 percent who can be defined as true omnichannel shoppers — toggling between physical and digital channels with the same merchant — report a consumer satisfaction benchmark of 41.3. More than 80 percent of consumers know that the merchants they shop have a mobile app, and 50 percent of them have downloaded it.

The biggest drivers of their lackluster performance reflect a failure to know the consumer across all shopping touchpoints — and in such a way that it’s obvious to the consumer: the inability to personalize offers and recommendations based on their history and behaviors and the inability of consumers to use the same method of payment regardless of the channel used.

Here’s looking at you, digital wallets.

This poor performance doesn’t seem to keep consumers from shopping at those retailers. Habituation is what drives consumer shopping behavior and spend at the physical retailers they visit today.

A staggering 94 percent of them who shopped large stores and the 86 percent who shopped smaller stores say they do so because they’ve shopped there before. Seventy-five percent of consumers who shop larger retailers and 52 percent who shop at smaller ones also knew what they wanted to buy before they went inside to shop.

Most of the spend from the consumers in our study is concentrated among a handful of big brands: Walmart, Target, Amazon, Costco/Kohl’s and Macy’s round out our big five.

Maybe some of you may not think that’s much of a new story.

After all, most consumers have today and have always had a handful of stores that are their “go-to’s” because they know that store, are confident in the quality and availability of what they typically buy at that store and it’s in a convenient location. And it’s often those big names and big brands with scale that are easy to access and offer a wide variety of things at a good price.

What’s interesting is the degree to which mobile devices with GPS and the myriad of innovators pushing coupons and offers and even push notifications hasn’t changed consumer behavior much at all, even if an offer is pushed to that consumer when they’re within striking distance of a retailer.

And that’s the third big insight: Consumers make their decisions about what they want to buy — and where — well before they get to the store. Promotions and offers marketed to them when they’ve started their shopping mission don’t say them. Only 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively, of consumers said they visited the store they had just left because an offer or a promotion drove them there; even fewer than that (2 and 1 percent, respectively) did so because they searched online and discovered a new place to shop.

More generally, fewer than half (43 percent for both large and small stores) chose a brick-and-mortar retailer because of a special promotion that was sent to them, and fewer than 40 percent (38 percent and 30 percent) did so after receiving an offer.

Payments habits, it seems, aren’t the only ones that are hard for consumers to break.

And for retailers, and the ecosystem around them, to change…

The Retail Road Less Traveled

If you’re one of the top five retailers in our study, you might be feeling pretty good right about now.

Entrenched consumer behavior, even if there are big omnichannel misses, keeps a large majority of your consumers coming back. They know you and know what you offer and have decided you’re the one before they get to the front door. Even deals and offers doesn’t lure them away. Consumers don’t like taking the road less traveled when shopping. Change means risk, and risk means uncertainty, and uncertainty costs time and money. In today’s busy world, and with many consumers living paycheck to paycheck, that’s the kind of risk consumers actively seek to avoid.

Or, then again, maybe you’re squirming a little bit because you know that Amazon and Kohl’s is a matchup with the potential to go well beyond Kohl’s serving as a logistics hub for Amazon returns and a showroom for Alexa.

Making it easy for Amazon Prime customers to pull into a Kohl’s location — which doesn’t require navigating malls and mall parking lots — checks an important omnichannel box Amazon lacks: buy stuff online, make it easy to return to a physical store that’s convenient to the consumer.

It’s also a chance to convert the non-Prime customers who shop Amazon and Kohl’s and prompt them to spring for a Prime membership. Amazon returns inside Kohl’s stores will also be a reminder to those Kohl’s customers who already shop at Amazon to shop there even more, since returns are easy peasy at a retailer they visit anyway. Maybe Santa Amazon will even gift Kohl’s customers a discount on a Prime membership; you never know.

The hope for Kohl’s, of course, is the potential to monetize the big-spending Amazon Prime member feet that accompany those returns. This new source of foot traffic might even entice brands to design exclusive experiences in Kohl’s stores to get those customers to buy their merchandise too.

Including Amazon, with its own private label products: apparel, kids clothes and its Essentials products, inside Amazon-branded storefronts staffed with Amazon sales associates.

That’s, of course, what’s happening already on a limited basis. Kohl’s is dedicating real estate inside its stores to sell Amazon/Alexa-branded products. Amazon sales associates will demonstrate and sell — and install — the suite of Alexa devices that will power an Alexa-enabled smart home, enabled via Amazon Pay and an Amazon Prime membership.

Speaking of Amazon Prime, Prime members drive 57 percent of Amazon’s North American revenue, and adding more fuel to that revenue pump is important. And Kohl’s customers seem like prime (haha) targets — shoppers are largely female (80 percent) with an annual income of roughly $70,000. Nearly a third live in households with annual incomes of $100,000-plus.

Perhaps it’s now clear why Amazon and Kohl’s, together, has the potential to put a brand new spin on the convergence of digital and retail channels and how to serve customers at those many new touchpoints.

Playing with Payments

What we also know from our study is that consumers complain when they can’t use the same method of payment across all the channels they shop. So, too, is knowing that they’re getting the best deal without having to stay on top of the retailer at every turn to be sure.

It’s been reported that there are 25 million active Kohl’s charge cards in circulation and that roughly 60 percent of Kohl’s sales are generated by consumers using those cards. Consumers buying things inside the Kohl’s app can’t use any other payments product when they do make a purchase.

At the moment, Amazon doesn’t allow consumers to register store cards other than its own — it never needed to do so.

Nor does it allow a consumer to register another digital acceptance mark — it never wanted to (and probably never does).

Amazon’s omni ambitions seem quite clear — in its own branded bookstores, with its Alexa-powered experiences, using its Pay Places order ahead and soon its Olo-powered restaurant delivery programs and what’s likely to evolve at Whole Foods — Prime membership and Amazon Pay are the keys to delivering consumer value.

Kohl’s ambitions seem clear too: delivering value through its high-margin, store-branded payments product, giving the best deals and offers to customers bearing those store-branded cards.

Will the combination of the consumer’s trust in and use of Amazon help Kohl’s break the habit of consumers who shop at their competitors and get them to switch?

Is Kohl’s a possible outlet for Amazon-branded products — including groceries such as canned goods, laundry detergent and other staples that don’t require refrigeration? Kohl’s new CEO, it’s worth nothing, comes from Supervalu foods. Just how far will the Kohl’s and Amazon omni-experiment go — and what role will payments play in creating a smooth consumer experience for both?

It’s far too early to know or even speculate.

For now, all we know is that purchases of Alexa devices inside Kohl’s stores will be made the same way they are now: paid for via Amazon Pay inside the Amazon mobile app. Purchases of everything else bought inside the store will the paid for the same way that Kohl’s customers pay for things now, including the use of its store card.

How that might change will depend on how much uptake there is of Amazon’s offer to accept returns at Kohl’s, whether any increase in foot traffic results in increased sales for Kohl’s and how effective Kohl’s is as an incremental sales channel for Alexa and Amazon Prime memberships. It’s certainly not out of the question to consider that an Amazon app could be enabled to check a consumer in when she walks into Kohl’s and to check her out via that app when she leaves with her purchases or is divested of her returned goods.

Now’s probably a good time for retailers, payments players and innovators to take stock of the retail — and omnichannel — landscape and plan what’s next, keeping in mind that Amazon is already about five moves ahead.

We’ll see how it all unfolds soon enough. The upcoming holiday season will be as good a litmus test as there ever could be for watching all of this happen in real time — and will answer the question: Have Kohl’s and Amazon, together, ushered in the new breed of omnichannel retail?

And was Kohl’s decision to take the retail road less traveled, indeed, a wise choice?

Unlike the traveler in Frost’s poem, for Kohl’s, taking the road well-traveled probably wasn’t really much of an option anyway.