The most interesting story about Facebook since the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke is one that hasn’t really been written.

And it’s the one about the value platforms can create for their customer groups, at scale.

Despite the news over the last year or more about its involvement in fake news, election tampering and user data breaches – and even before that about the bullying, live beheadings and murders broadcast and shared on its platform – people still show up at Facebook’s doorstep every single day.

Billions and billions of them, and more new ones every quarter.

In the year since the near daily coverage of Facebook’s missteps over the 87 million users whose data was used without their knowledge or permission, Facebook’s revenue has soared.

And its user base has grown.

All of those things might help to explain why, despite The Wall Street Journal’s reporting on Friday (July 12) that the FTC had reached an agreement to fine Facebook $5 billion, the company’s stock closed at $204.87, up $3.84 (1.81 percent).

The Facebook Friday

As The WSJ noted, the fine that the FTC is ready to impose against Facebook will be the largest ever against a technology company. It is reported to result from a 3(R)-2(D) decision by commissioners after determining that the user data issues related to the 2018 Cambridge Analytica breach violated the 2012 consent decree Facebook entered into with the FTC. That breach started a groundswell of bi-partisan support for fines, other penalties related to governance and personal liability of Facebook’s CEO, new regulations – and even the breakup of the company.

This news comes from “persons familiar with the matter,” and neither the FTC nor Facebook have commented. What’s not yet known is the extent to which some or any of those other remedies may yet be imposed. Those familiar with the matter add that the reported remedy is also sufficiently vague about other actions, including those against Mark Zuckerberg personally, if it can be proven he had knowledge of Facebook’s user data lapses.

Market pundits say Facebook’s uptick in stock price can be attributed to the fact that a big fine was already baked into that price.

On Facebook’s last earnings call, Zuckerberg signaled that they were reserving $3 billion in anticipation of such an FTC action. As a company with a market cap of $584 billion, Facebook has about $45 billion in the bank, and generates about $5 billion in free cash flow per quarter. That makes a $5 billion fine the corporate equivalent of a large traffic ticket – a nuisance to have to pay, but not something that will jeopardize the company’s financial standing. After all, it’s not like it was $15 billion – so what’s the big deal?

Platform pundits, like me, attribute the stock price jump to something more intrinsic to the business Facebook has built over the last 15 years: the value of the platform to its stakeholders, despite its recent scandals.

The Power of the Platform

Last quarter, Facebook reported that its active daily users crossed the 1.5 billion mark to 1.56 billion, up 8 percent.

On average, they reported, more than 2.1 billion people used at least one of the apps in the Facebook family – Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger or Facebook – every day, and 2.7 billion using them every month.

User growth is clipping along in developing markets like India and the Philippines, and still growing – albeit more modestly – in developed markets like the U.S. and Canada.

Those eyeballs bring with them the money side of the Facebook platform: advertisers.

Facebook reported that its Q1 total revenue was up 26 percent to reach $15.1 billion, and its total ad revenue was up 26 percent at $14.9 billion. Mobile ad revenue grew 30 percent year over year, as did the diversity of its advertiser base. In Q1, Facebook reported that its top 100 advertisers represented less than 20 percent of its total ad revenue – not because the big guys are pulling back, but because the long tail of advertisers is jumping in.

Ad growth was strongest in the U.S. and Canada – up 30 percent – followed by Asia-Pacific, at 28 percent. Europe grew more slowly, at 21 percent, in part given the increase in the number of consumers who opted out from having their data used to more precisely target ads to their feeds. Facebook’s CFO cited GDPR as an ad-targeting “headwind” that could interfere with its performance in Europe and in other markets that could adopt similar regulations going forward.

Admittedly, Facebook’s growth in both users and ad revenue sounds rather counterintuitive for a platform that has been implicated playing fast and loose with its users’ data.

But advertisers keep showing up, because consumers keep showing up.

And consumers keep showing up – because they find value in how they use the platform today.

Even though they also say they don’t trust Facebook the same way they once did.

Trust, but Adjust

Consumer Reports did a study of American consumers in May of 2018, shortly after news of the Cambridge Analytica scandal broke – and then again in January of 2019.

They found that despite thinking about and threatening to disconnect from the platform, only 10 percent of Facebook users actually did so. The other 90 percent remain solidly engaged because they value the ease with which they can stay in touch with friends and family (72 percent) and participate in and get information about groups (25 percent).

What we don’t know is whether the 10 percent that dropped Facebook used it all that much to begin with.

The reason consumers stick around is that Facebook makes it easier for its platform stakeholders to interact – and thus enable the platform to monetize those interactions and scale.

That’s what platforms do – or, at least, the platforms that live as long as Facebook.

Platforms that deliver great value figure out where frictions exist, and then use a variety of strategies to assemble a critical mass of customers on one side who will appeal enough to a different group of customers so that they will pay to access them. Platforms then play the role of matchmaker in bringing those sides together and monetizing those interactions.

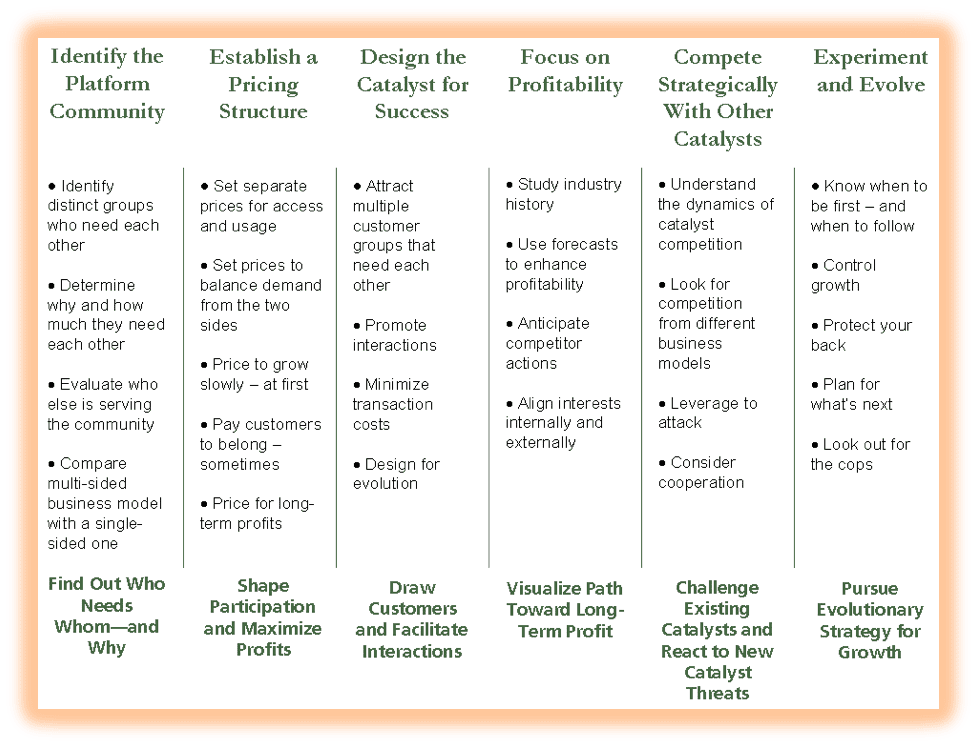

This platform framework, one that my colleagues at Market Platform Dynamics and I first introduced publicly back in 2007, shows the platform playbook in a step-by-step process. It’s a framework that first appeared in a Harvard Business School book that we wrote and published that year, titled The Catalyst Code: Understanding the Secrets of the World’s Most Dynamic Companies.

The Facebook platform formula is well-known: First, get college students and their friends on board, then more and more people as they bring their respective social networks to the platform, and then advertisers who want access to those eyeballs.

It’s a platform framework that also helps to explain why Facebook remains resilient, even when advertisers and consumers have other options: the friction for both sides to leave is far greater than for both sides to stay.

As long as that remains true, advertisers will keep showing up, and so will consumers.

And Facebook’s platform will continue to grow.

The Catalyst Framework

Source: Market Platform Dynamic

All that being said, over the last year, Facebook users have changed the nature of their interactions with the platform.

According to the same Consumer Reports study, 44 percent of Facebook users have changed their privacy settings, 39 percent have blocked certain users, 38 percent have curtailed posting comments, 37 percent have turned off location tracking on the app and 34 percent have blocked advertisers, up from the 28 percent reported in May of 2018.

The “half-empty” view of those stats might suggest that as users are taking more control of their settings and blocking access, advertisers and Facebook will increasingly be pushed out.

The “half-full” view is that consumers’ ability to more precisely control who can access their data and show up in their news feeds is an innovation that will help keep the value of the platform strong for both advertisers and consumers.

Considering the media bashing about ad-supported platforms, consumers don’t mind seeing ads as much as one might think. In fact, according to eMarketer, only 25 percent of all internet users block ads.

Consumers especially don’t mind seeing ads that are targeted to their interests – but they do mind getting ads for things that aren’t. The only way consumers can get a better experience is if advertisers have relevant user information, and the ads they serve make those matches possible. Consumers are smart enough to know this – and they accept it.

Facebook, by providing stronger privacy settings and allowing consumers to block advertisers they don’t want to see, is actually a platform value-add.

It helps advertisers get better data about who doesn’t want to see their stuff (so they don’t pay for worthless clicks), helps Facebook save money by not showing ads to consumers who probably won’t click on them and instead giving them something they will (which is how the company makes money), and helps consumers see ads – and posts – that better align to their interests (which keeps them coming back).

Facebook and Payments

These survey results, and Facebook’s quarterly results to date, show that consumers find Facebook valuable as a way to stay in touch with friends, family and groups, and to see targeted ads as part of that experience.

Since the Cambridge Analytica scandal, though, users have expressed an increasing distrust of Facebook: 25 percent say they are “extremely” concerned about how Facebook uses their information. And, as the earlier stats show, they are being more proactive about who gets that access.

That still leaves a lot of people who don’t block ads and keep coming back. But lots of people aren’t concerned, don’t block ads and keep coming back. That doesn’t mean Facebook has – or will ever have – earned enough trust to expand its use beyond just a social network and an advertising platform.

Specifically, an expansion into payments and financial services.

Commerce and payments have long been on Facebook’s roadmap, well before Libra’s launch. Over the years, those efforts have languished on the Facebook platform. Facebook executives say transactions on Marketplace are is growing, but little more than a rounding error in terms of financial results: $14.9 billion of the $15.1 billion in Q1 revenue was all driven by ads.

The fact can’t be all that surprising to Facebook, user data scandal notwithstanding.

When it comes to their money – where consumers keep it and how they spend it – study after study show it’s with brands consumers trust, and with which they have first built a trusted commerce and payments relationship. That’s their bank, the card networks, FinTechs like PayPal, merchants like Amazon and Walmart, and the mobile wallet players like Grab, in developing countries, WeChat and Alipay, in China. (Yes, WeChat is the exception to that rule, but so is China and how WeChat started.)

The 2018 update to our annual How We Will Pay study of 6,000 U.S. consumers showed that Facebook was dead last in a list of who consumers would most trust to innovate their payments experience – a study done four months after the details of the Cambridge Analytica story were made public.

Our more recent study on Where We Will Bank?, done earlier this year, which identifies brands that consumers might have an interest in banking with, showed that Facebook’s results were only slightly different.

What’s Next

A platform that has created enormous value by making it easier for consumers to stay in touch with each other isn’t logically the same platform that can easily make the transition to the “super app” that consumers then use to manage and spend their money.

Nor should we – or they – even expect that.

It’s not even clear that the transition from social network to commerce platform would have been possible, Cambridge Analytica scandal notwithstanding. And now that it’s front and center with lawmakers and regulators, it’s a transition that seems off-base and off-track.

The fifth pillar of The Catalyst Framework is about evolving the platform – scaling it, finding adjacencies that can leverage its platform assets and new ways to monetize its customers. It also cautions to “look out for cops” – which, in the platform world, are the regulators.

Regulators can be a more powerful disruptor to platforms than competition, because they also have the power – through regulation – to attack the money side of the platform. For Facebook, that means how they use data, because at its core it is an advertising platform on top of a social network, and the ability to use data to target advertising is how it makes money.

For Facebook, the cops – the regulators and Congress – want their pound of flesh. The ill-timed launch of the ill-conceived Libra, and Calibra, and its new rails and cryptocurrency, has only added more fuel to their arguments.

They want a breakup, whatever that means – although it sounds tough, it is potentially a move that could add more value to shareholders.

They want fundamental changes to the Facebook business model – yes, let’s tell voters that Facebook should charge them for access to their friends’ networks.

They want Facebook to transfer more control to the consumer over how data is captured and accessed –which seems like a winner to me, and something Facebook has already started to do, although perhaps too little and too late for the regulators’ taste.

The more these regulators and policymakers dig in, and the more successful they are, the less valuable the Facebook platform will become for consumers, and then the less valuable it will become for advertisers.

What Facebook has going for it is that an awful lot of people, and voters, seem to love it, despite last year’s events. So maybe at the end of the day, it’s possible that the politicians and regulators will just vent to look good to the public and to voters – and push to the back burner any actions that could crater the value of the platform consumers seem to like and use.

The ill-timed launch of the ill-conceived Libra, and Calibra, and its new rails and cryptocurrency, has only made that harder. Even though, ironically, that’s how Facebook would like to hedge its bets against whatever regulators have in store.

The market reaction to the $5 billion Facebook fine on Friday was that it was no big deal, and that the value of the Facebook platform will prevail.

I guess we will have to wait and see.