When Will Consumers Cut The In-Store POS Cord?

Will millennials and Gen Z cut the cord on traditional points of sale in retail?

Netflix first introduced its streaming service in the U.S. in January of 2007. It landed with a bit of a thud with analysts and pundits.

Media accounts then poo-poohed its impact, claiming that users would have to <gasp> download a piece of software onto a PC to access content, and pay more to subscribe to a service with a limited content catalog (1,000 shows) — and who’d really want to do that? Content creators would never cut deals with Netflix, they speculated, because doing so would only cannibalize their own businesses and business models. And since streaming was never going to go anywhere anyway, why would they even bother?

Some analysts concluded at the time that those frictions would only serve to boost the fortunes of Blockbuster, the de-facto brick-and-mortar leader in distributing physical DVDs. At the time of the announcement, Blockbuster’s stock price even ticked up as they pointed to a “staggering” number of net new subscribers to their service in November of 2006.

We all know the next chapter of that story.

Three years later, Blockbuster went bust as streaming options moved from the desktop to mobile devices and TV sets, and digital ate the frictions of physical content distribution.

Blockbuster wouldn’t be the only casualty of Netflix (or streaming). The shift from DVDs to streaming also shifted the competitive dynamics of content creation and distribution to the providers that could most efficiently deliver it to the slew of connected devices — including televisions — that consumers would use to watch content whenever and wherever they wanted. And away from the traditional and entrenched pricey cable TV providers, with their ad-ladened channels and pay TV add-ons, not to mention the satellite and other similar providers.

It’s a cautionary tale — one with many similarities between the consumer’s shift to streaming over the last 14 years and the consumer’s shift to digital over the last 14 months.

That shift to digital, as PYMNTS defines it — doing more in the digital world and less in the physical world for the same activities, such as grocery shopping and buying retail products — is characterized by the same competitive dynamic. And just like cable’s cord-cutters and cord slimmers, consumers will move away from the traditional and entrenched providers of shopping and checkout experiences to those that can most efficiently meet the consumers’ new, digital-first habits and preferences.

In fact, they already have.

Like streaming’s shift away from traditional cable, it will be the millennials and bridge millennials who lead the way.

Like streaming’s shift away from cable, it will be a gradual build, followed by a sharp acceleration up and to the right to those providers who deliver newfound shopping and paying preferences for these digital shifters — and down and to the right for those who can’t or won’t.

And like streaming’s shift, traditional players will likely poo-pooh the potential of these ever-more connected consumers to put a big dent into their universe until it happens — when the momentum of their digital shift becomes a fierce headwind that many may find too difficult to overcome.

Those Crazy Cord-Cutting Kids

Streaming’s 2007 cord-cutters tell the story of shopping’s 2021 digital shifters.

In 2007, Netflix and its streaming service birthed the first generation of cord-cutters and cord not-as-muchers — consumers who found a suitable and welcome escape hatch from cable’s bloated bundles.

The early cable cord-cutters were the millennials — the early adopters of smartphones and other connected devices who didn’t want to pay a hefty price for channels they didn’t watch, because it was the only way they could watch the movies they wanted to see. By the time Netflix celebrated its 10th birthday, a study conducted by PwC in 2017 reported that 90 percent of consumers ages 25 to 34 were accessing television content via the internet. Content creators that wanted to reach those valuable eyeballs had (and still have) no choice but to jump on that streaming content train.

Over streaming’s first 10 years, between 2007 and 2017, consumers could choose between multiple streaming providers — Netflix and others — to build their own best-of-breed bundles, including access to live television services from Hulu, YouTube TV and Sling. Increased competition meant that content programming got better. Televisions became internet-enabled, and Fire TV, Apple TV and Roku brought streaming content into living rooms and family rooms. Consumers could increasingly feel more confident that cutting the cable cord wouldn’t mean going without the programming they wanted and needed, including sports.

And cut it they did.

According to Pew Research, in 2015, only 24 percent of Americans were without a cable TV or satellite subscription; in 2021, 44 percent of Americans no longer have one — a nearly 50 percent decline in six years. Pew also reports that the nearly four out of every 10 Americans who don’t have a cable or satellite subscription today never did — the “cord-nevers.” And Pew reported that the majority (71 percent) of the 61 percent of consumers who used to subscribe to pay TV now get the content they want online from other providers — for cheaper.

Even more interesting, 45 percent of those without a cable or satellite service say they don’t watch TV. Streaming, it seems, has not only given consumers more options to access and consume content, but it’s also shifted their behaviors away from the content and the channels that used to define what it means to “watch TV.” That includes consumers getting their local news from online content providers instead of traditional television stations, and getting their sports – once the key reason that so many cable TV subscribers hung in there – from other streaming services.

But more than the decline of cable (and satellite) TV subscribers over the last 14 years is how it happened.

Death By A Thousand Cord Cuts

MoffettNathanson reported that 2020 was the worst year for cable TV subscriber growth, with providers losing six million subscribers in a single year.

that 2020 was the worst year for cable TV subscriber growth, with providers losing six million subscribers in a single year.

Annual subscriber losses didn’t always cut so deep. In fact, according to this chart, it would take roughly eight years before the loss of cable TV subscriber growth would move beyond a sub-1 percent decline quarter over quarter. For cable TV providers, the loss of subscribers was more or less death by a thousand cuts of those cords: concerning at first, but not enough to push the full-on panic button — until a tipping point in the wrong direction in Q2 of 2015 set up what would become a steady and steeper downward spiral.

It would be the millennials and the bridge millennials who would drive much of that decline.

Retail’s Digital Shifters

Retail’s $4 trillion question is how many of the digital habits honed by consumers over the last 14 months will stick, particularly as vaccinations are finding their way into people’s arms at a record pace in the U.S. and quarantine-weary consumers anxiously await a return to the physical world.

Retailers say that eCommerce has seen a massive growth surge over the last 14 months, but from a relatively small base. Despite eCommerce driving more than $900 billion in incremental volume globally, according to Mastercard, 80 percent of sales still happens in the physical store, retailers contend. And the physical store is where consumers will return, because they have gone without shopping there for so long.

It’s a little like cable TV in the 2010s.

According to PYMNTS’ research of collectively more than 50,000 U.S. consumers over the last 14 months, 117 million of them have done two things simultaneously over that space of time: They have used digital channels to shop for groceries and retail products more often, and have used physical channels to do their grocery and retail shopping less often.

Like streaming’s cord-cutters, this new retail persona — the digital shifter — is creating her own best-of-breed shopping experiences using her mobile device, using apps to order and pay ahead, and choosing the merchants who can support her newfound, digital-first preferences.

It isn’t as if digital shifters are dissing physical stores entirely, but they are definitely using them differently.

What’s more, these digital shifters are not likely to flip a switch and “go back.” Nearly 90 percent say they will continue to keep their digital/physical splits intact, even as they become more comfortable getting back into the physical world. That means that a snap back to the physical world may well be characterized less by the things for which digital is an effective and efficient substitute — and more by the things for which it is not: traveling to see family and friends, going out to eat, strolling up and down Main Street on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon to shop and have lunch, or going to ballgames and concerts. That is, all of the experiences that many of us have missed so much over the last 14 months. The experiences that consumers want to have in the store and is worth their time instead of trips to the store for the essential items they can just as efficiently get online.

Like steaming’s cord-cutters, millennials and bridge millennials — the cohort of 33- to 43-year-olds who straddle millennials and Gen X — will propel this digital shift and keep it growing. Like cable TV’s cord-cutters, they are the generation with spending power and a digital-first preference. Bridge millennials are the first generation that grew up with connected devices, and that defaulted to using them to shop, pay, bank, stay connected and otherwise navigate an increasingly connected economy. They are using new digital tools to shop at the merchants they love and discover — and buy direct — new brands that reflect their social and cultural preferences.

Of the 117 million consumers who have shifted digital for retail or grocery purchases, 17 percent of them are millennials and 14 percent are bridge millennials. That’s a small fraction of consumers, to some, but a cohort whose spending power and digital preference looms large — and will shape the futures and the fortunes of retail.

The Consumer And The Point Of Sale

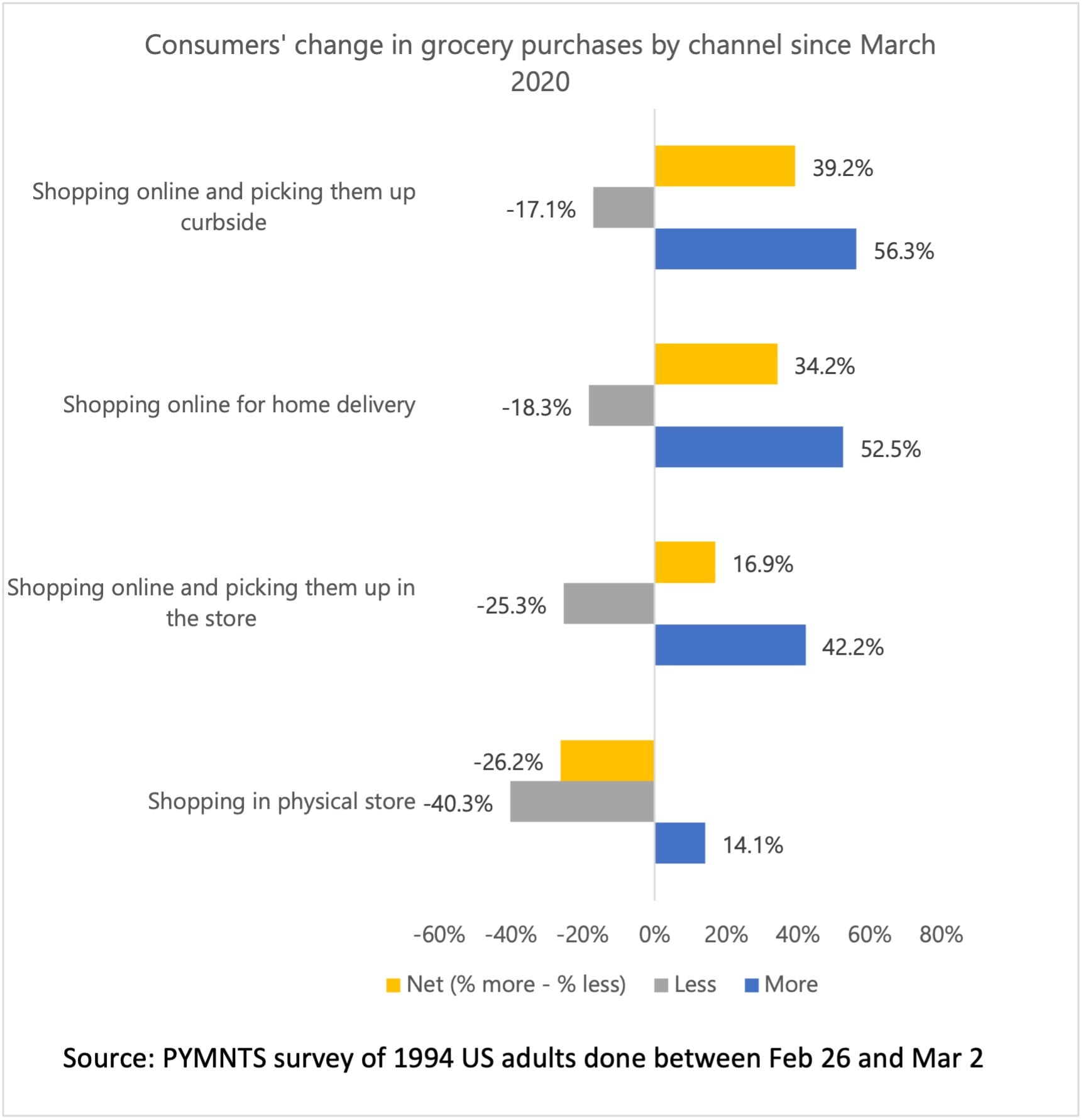

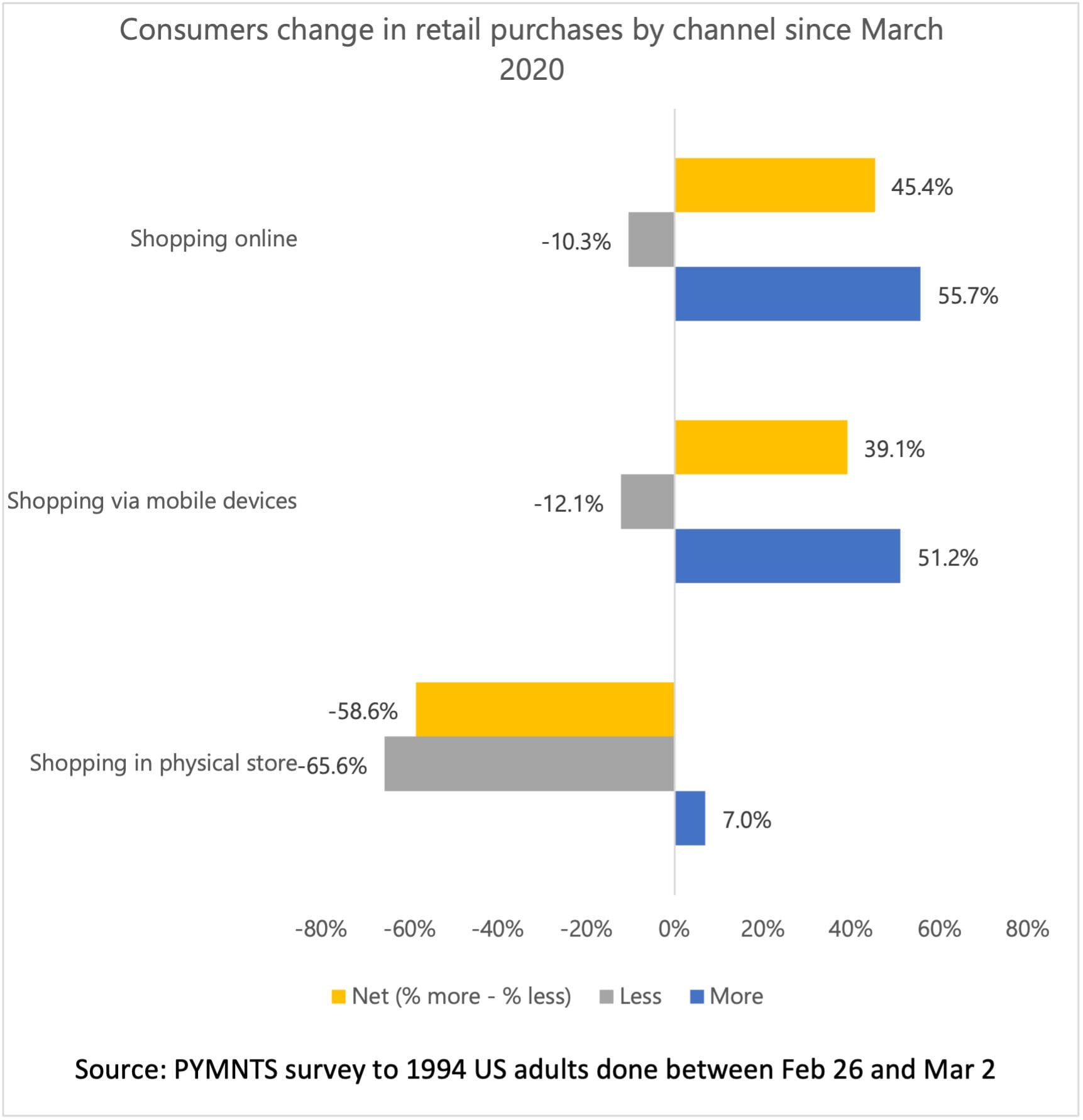

One of the most profound insights from PYMNTS’ research over the last 14 months is the consumer’s increasing preference for living in a “bring it to me economy,” a trend I first wrote about in January of 2021. The most recent pandemic-related PYMNTS survey of 1,994 consumers conducted between Feb. 26 and March 2 underscores this trend.

As you can see from these charts, consumers shop for grocery and retail products using both digital and physical channels — the very definition of a Digital Shifter. But the net shift by shopping channel is not only more toward digital, but to the digital options that give consumers more control over the time they spend shopping and paying for their purchases: order online for delivery, and order online to pick up curbside.

As you can see from these charts, consumers shop for grocery and retail products using both digital and physical channels — the very definition of a Digital Shifter. But the net shift by shopping channel is not only more toward digital, but to the digital options that give consumers more control over the time they spend shopping and paying for their purchases: order online for delivery, and order online to pick up curbside.

Net shift is defined as the difference between consumers who did more in more in one channel and less in another.

For grocery shopping, the net shift reflects a negative net 26 percent away from the physical store channel, and a net positive shift of 34 percent to buy online for delivery and 39 percent to buy online and pick up curbside for all shoppers.

For bridge millennials, that net shift away from the physical store for groceries and the shift to online ordering for delivery is more pronounced: a net negative shift of 34 percent away from shopping in the physical store more generally, and a net positive shift of 40 percent for retail purchases and a net positive shift of 36 percent for grocery purchases that are online order ahead for delivery at home.

And for bridge millennials and millennials, the ultimate touchless experience today is not going to the store to shop and to pay. They, and the devices they have within their control, have become the point of sale.

The Consumer As The POS

For cord-cutters, the shift away from cable TV was more than just a shift away from “cable” or “satellite” — it was a break from a provider with a proprietary piece of hardware that consumers had to install and pay for to access programming. Consumers were stuck with a box or a dish — and only the programming they could get from them.

Connected devices and streaming content gave consumers control and choice — an on-demand content experience, wherever, whatever and to consume whenever they wanted. Over time, consumers used streaming more, cable TV less (and some not at all), and (before COVID-19) the movie theater to watch studio blockbusters. Consumers adjusted their bundles — more of this, less of that — established new content consuming habits and preferences and were willing to pay for having that choice.

Retail’s Digital Shifters are in the process of doing the same thing: exercising their desire for control and choice in how they shop, and how they pay for what they buy. They have more choices and options now to consider, and retailers are stepping up to provide those choices. Standing in front of a terminal to check out had already become less and less desirable even before COVID, and order ahead for pickup was already gathering momentum, particularly in the grocery and QSR channels where speed and convenience is critical. And despite the ability for consumers to use contactless cards to checkout. Contactless cards didn’t reinvent the point-of-sale experience for consumers — they just made it a bit faster, and now, more health-conscious. They still had to queue up to stand in line, and wait for the cashier to bag their items before leaving the store.

Connected devices and apps put the power of the POS in the hands of consumers and an opportunity to cut the POS cord, even when they shop in the physical store. QR codes and other app-based innovations will help consumers not only pay when their shopping is done, but also to have a smarter, more personalized shopping experience, regardless of the channel they shop and where they are when they take possession of what they bought.

Innovators understand and will seize the opportunity to erase the physical and digital shopping divide by reimagining the shopping experience and moving it to the cloud, and under the control of the POS cord-cutting digital shifters whose numbers will continue to grow — and retailers ignore at their peril.

And depending on when you started counting, that reality might arrive faster than you think.