What Spontaneous Commerce Can Teach Online Retailers And Payment Providers

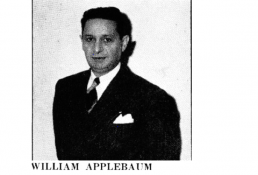

In January 1950, William Applebaum published a piece in the Journal of Marketing about the buying behaviors of consumers in retail stores. At the time, Applebaum was the director of Marketing Research at the Stop & Shop supermarket chain based in Boston. The research he presented in that paper, however, was conducted a dozen years earlier — over the five-year period between 1932 and 1938 when he was employed at Kroger.

Applebaum’s interest then was to better understand the who, what, when, where, why and how of those consumer behaviors. His observations, now some 67 years later, remain central to today’s modern-day retail marketing, merchandising and promotional strategies.

For instance, he observed then that urban dwellers shop and buy differently than their more rural counterparts and that store merchandise and amenities must reflect those differences.

Applebaum also observed that the person doing the shopping was buying things influenced by other members in the household, even those without any direct purchasing power themselves. He said to know what consumers will buy meant understanding the profiles and interests of those influencers, even children and household pets.

He concluded that a consumer’s loyalty to grocery stores was fleeting, often price-driven, and influenced increasingly by the availability of amenities like parking and store credit.

He also wrote that efforts to influence when consumers shopped for groceries (as a way to manage congestion in stores) was ineffective — that consumers had their own schedules and expected stores to adapt rather than the other way around.

Applebaum’s research also revealed that consumers shopped at multiple stores for groceries, observing that they often used one store to buy “dry goods” — staples — and others to buy “wet goods” — meats, produce and dairy — even if all of those items were sold in the same store. That behavior, he said, put all stores at risk to losing customers to competitors, and that smaller specialty players (in those days, the milkman) still occupied a very important place in the grocery store retail mix.

Yes, the future of grocery as foreshadowed 67 years ago. And now brought to you by the makers of Amazon and Whole Foods.

Applebaum ended his paper by outlining an important piece of unfinished business — a call to action for researchers to understand better the impact of promotional advertising in influencing a shopper’s intent to buy the things that weren’t on their shopping lists when they walked into the store.

Research into the effectiveness of in-store signage and displays, demonstrations and “sales talks” — the banter of friendly cashiers and sales associates — he felt was historically too “flawed” to be reliable.

Yet too important an area of understanding in how to increase sales to be ignored.

What Is an Impulse Buy?

Impulse buying is defined classically by researchers as an unplanned decision made by a consumer to buy something in the moments just before the purchase is made. For retailers, it’s always been defined as an important source of incremental sales.

These impulse buys have historically been associated with the collection of relatively inexpensive but high-margin items displayed at grocery stores checkouts while consumers wait the six or seven minutes, on average, it takes for the person in front of them to get through the line.

Source: assemblyman-eph.blogspot.com

Or walk past the attractive displays situated at aisle endcaps.

Or when offered as part of live cooking demonstrations or left out as samples for shoppers to try while cruising the aisles (hopefully hungry), which appeal to both the shopper’s visual and olfactory senses.

Scientists say these unplanned purchase decisions happen when the frontal lobe of the human brain responsible for a human being’s higher order decision jumps into action and decides it’s the thing to do.

For instance, my frontal lobe decided last week that I couldn’t live without buying Cook’s Illustrated Best Ever Recipes magazine at the Whole Foods checkout — a purchase I had no intention of making until I saw the scrumptious-looking dish on the front of the magazine.

I’ll bet your frontal lobes have decided that you needed to throw that package of gum or mints or chocolate candy bar or lip balm or magazine that you never intended to buy onto the counter or the conveyor belt during one of your last grocery shopping trips too.

More broadly, the data suggests that there are a lot of frontal lobes hard at work in grocery stores.

These types of unplanned purchases are said to account for 1 percent of all grocery spend — and in the U.S., that’s more than $6 billion annually.

But what I now am calling Spontaneous Commerce isn’t just happening at grocery stores and is starting to influence what consumers buy and how they buy them.

A 2013 study suggested that the average consumer spends a little more than $118 a year — or nearly $115,000 over the course of her lifetime — on impulse purchases — things one never intends to buy.

In addition to the typical roster of food, candy and magazines, consumers say they buy clothing, toiletries and even shoes that way now. On Black Friday this year, 35 percent of consumers surveyed by Statista said they made unplanned purchases of clothes, and 24 percent made unplanned purchases of games while shopping in stores that day.

Spontaneous commerce is often prompted by many of the same visual cues that have always set the consumer’s frontal lobes in motion: putting things that are typically high margin and/or not terribly expensive and/or not complicated to buy at or near the places in stores that consumers pass by often and/or are forced to stare at while waiting in line.

Today, however, impulse buyers are as different as the things consumers buy — and those distinctions come with an important difference.

A difference that, if well understood, can help retailers drive incremental sales in important new ways.

Who’s Buying What on a Whim?

Researchers who’ve studied unplanned shopping behavior have classified impulse shoppers into four distinct buckets. All share one common characteristic — the item or items they buy aren’t planned in advance — but these buyers don’t always buy something that’s totally new to them.

The hybrid impulse shopper, for instance, knows generally what she wants to buy but makes her final decision on the basis of price, coupons and other inducements in the moment. Think of this as the shopper who knows she wants to buy a black sweater but decides what type of black sweater and where to buy it on the basis of the store that offers her the best deal.

The recall impulse buyer sees something that she probably buys a lot but hadn’t planned to purchase on that trip to the store. This is the shopper who sees mozzarella cheese on display in the produce section while buying tomatoes and remembers there’s no more at home.

There’s the purist, who sees something totally out of the normal buying experience but buys it anyway regardless or need or familiarity with the product. This is the woman who buys a bottle of bright red glitter nail polish at the cosmetics store checkout but never paints her nails. Researchers say that these purchases often come with a heavy dose of regret, given the degree to which they depart from the consumer’s typical buying pattern.

Then, there’s the suggestion impulse buyer, the person who sees a product for the first time, imagines a need for that item and then buys it. This is the guy who’s at the hardware store buying drill bits and throws jewelry cleaner into the bag so that his fiancée can keep her new diamond engagement ring sparkly.

Now, it’s no accident that all the examples I highlighted happen in a physical store.

Roughly 80 percent of spontaneous commerce happens there. Retailers are using a number of tools and technologies and data to improve their chances of putting just the right items at just the right places in their stores to increase the likelihood that consumers will buy stuff they suddently can’t live without.

But retailers also have their bottom lines set on combining their understanding of the types and behaviors of impulse buyers with the growing number and usage of online channels and mobile apps used by consumers to up the odds that a consumer will take the bait.

Retargeting has always offered retailers the chance to nudge those hybrid buyers into buying the things they once looked at — often taking their chances by appealing to their price/coupon sensibilities to close the deal, even though click-through rates remain low.

Recommendations prompt those who may have never thought to try a particular type of product to do so, by making those unplanned purchases feel safer by reminding consumers that others like them with similar purchase patterns gave it their thumbs up.

Retailers appealing to the purists or hybrid types have taken a fancy to promoting “buy online, pick up in store,” since more than half of consumers buy more when they pick up their purchases — often buying things they hadn’t intended to before walking in.

Subscription commerce has mechanized the many so-called recall impulse purchases at a particular online retailer for as long as that item is used.

The ability to buy things in context — products viewed in the Facebook News Feed, presented as a shoppable ad on Instagram, shown as a hanging green tag on a product in Houzz, presented inside a messaging app or accessed by a link in a blog post describing a new or popular product — has introduced a world of new environments, giving consumers a way to discover and then buy something that was never on any of their shopping lists while they were actively shopping.

In each of these eCommerce examples, payment plays a starring role by making the purchase of those things easy, efficient and secure.

New research now emphasizes the importance of where — and what — payment choices are made known to consumers in those moments.

Two MIT professors, Drazen Prelec and Derek Dunfield, published a paper three months ago that examined the habits of consumers when shopping online. Like Applebaum decades before, they wanted to better understand the relationship between payment, a shopper’s purchase intent and incremental sales to the retailer.

As part of their work, they created an “Amazon-like” marketplace with millions of products for consumers to choose from and gave consumers access to it. The consumers who were part of the study used their own money to make their purchases.

Prelec and Dunfield have previously conducted research on consumer habit, what they describe as the “pain of paying” and the availability of credit products in enabling those purchases. This particular study concluded, perhaps not surprisingly, that access to a credit, and not a debit card, eliminates the pain of paying by reducing uncertainty over whether a consumer has funds available to complete an eCommerce purchase.

But it was their findings regarding spontaneous commerce — or a consumer’s unplanned purchases — that I found most intriguing.

In those cases, their research concluded, the difference between making an unplanned purchase and not making one depended on when consumers are shown what payments methods are available to them to make that purchase.

If a consumer knows at the time of what Prelec and Dunfield describe as the “fully reversible” purchase intent that they can use credit to make an unplanned purchase, they will make that purchase. If they are not shown those payment options until the consumer is at the “irrevocable payment decision,” their research concluded they will not.

Signaling that credit and/or payment methods that enable a purchase with a form of credit at the same time consumers are presented with an option to buy is the digital equivalent of aisle endcaps and stacking the checkout lane with gum, candy, mints and magazines.

It’s also a finding that we observed the last time we published our Checkout Conversion Index. Letting digital shoppers know, as far forward in their online shopping journey as possible, that there is a digital checkout option available to them increases that online retailer’s conversion rate.

Like a lot of things in payments, commerce and retail, what’s old is often new again — but with new tools and technologies to improve and accelerate the outcomes.

Like William Applebaum observed with his research in 1932, and published 18 years later, knowing who’s doing the buying — and for whom — is table stakes for any retailer. Convincing consumers to walk out of a store having bought things not on their shopping list was something he was convinced was the retailer’s holy grail.

More than 67 years later, and in the fastest-growing retail channel there is, we’re now beginning to understand the role of payments in helping retailers get there.

With perhaps the simplest insight of all — letting consumers know they can buy using a method of payment that eliminates their “pain of paying” when their shopping intent first surfaces, not after they’ve already decided that they can’t.