Amazon’s Retail Swiss Army Knife

At the ripe old age of 120, the Swiss Army knife holds a unique place in retail. The same family who founded it in 1897 still owns and run it today — all descendants of its founder, Karl Elsener.

Many of whom are also named Karl.

Many of whom are also named Karl.

Karl’s (the first) innovation put a spring on the handle of a folding single-blade knife that was the standard Swiss Army issue in the mid-1880s. That innovation made it possible for more tools to be added because they could be accessed from both sides of the handle without adding more bulk to the knife itself.

So, in 1891, Swiss Army soldiers were given a knife that contained a knife blade, can opener, corkscrew, screwdriver and scraper that all folded neatly into a small wooden handle.

Yep, a corkscrew — allegedly to make the knife more appealing to Army officers.

Karl’s vision of giving that folding knife more functionality by making the design more soldier-friendly drove the company to innovate further. Today tool attachments make it possible to have more than 300 different knife combinations and for a diverse group of customers, including moms and jetsetters. There are knife combinations that include everything from tweezers and toothpicks to saws and screwdrivers to laser pointers and LED lights and even encrypted flash drives with a fingerprint reader. The Swiss Army knife’s manufacturing process is said to be so meticulous that only one in 10,000 knives is ever returned.

Its design is so unique that it’s on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

And it’s so indispensable that, according to owners, it’s something that’s always with them.

Testimonials from Swiss Army knife owners detail a myriad of daily use cases (the all-important task of removing poppy seeds from one’s teeth after eating lunch, for example.) Others vow that “Someday I’m sure my Swiss Army knife will save my life, [so] I always have it with me, even when sleeping.”

Some recount situations in which the knife has saved lives — like the time that a 73-year-old owner of one freed a passenger from a burning car by using it to cut her seatbelt, just in case. Swiss Army knives are standard issue today by NASA to every astronaut.

And what better testimonial could there be than when TV good guy, MacGyver, famously said, “Give me duct tape, string and a Swiss Army knife, and I can fix anything.”

Which brings me to the news that broke late Friday afternoon (May 5) when photos of a new Amazon Echo device with a touchscreen were leaked.

Reach Out And Touch … Amazon And Alexa

Now, the idea of an Amazon Echo with a touchscreen is not exactly new — it was reported in November 2016 that mega e-retailer Amazon was working on such a device — whose code name is said to be the Amazon Knight. At the time, it was attributed to Amazon’s growing interest in using a touchscreen to enable Amazon Alexa-powered VOIP phone calls.

The reports that have flooded the tech cyber airwaves since Friday have more or less focused on that as its intended killer app — along with the ability to stream video from Amazon Prime in the kitchen while making dinner or, as one news account suggested, asking Amazon’s Alexa to show the kids what a real kid looks like.

All interesting, but not top of my list as Amazon Knight’s killer app.

What’s at the top of the list? Shopping, I believe. And, if and when it rolls out, the Amazon Knight app will underscore Amazon’s longstanding conviction that the reinvention of retail is about redefining what it means to be an omnichannel retailer

Personally, I’d like to think that the Amazon Knight was inspired by my oft-repeated fantasy use case for Alexa over the past couple of years: “Alexa, I’d like to buy that black dress on page 485 of this month’s issue of Vogue.”

Alexa then tells me what retailer has it in my size, confirms that I want to buy it, charges it to my card on file with Amazon and has it shipped to my home to arrive the next day.

In the case of Amazon Alexa + Amazon Echo with Touch Screen, Alexa could take that even further.

Alexa could send me a picture of said dress to confirm that it’s the one I really want. With Echo Look, Alexa could offer advice about whether it will look good on me based on the video profile I have stored with her. Then, I could buy it or ask her for another recommendation for something that might look even better.

Just like any good sales associate would — or should — do in a physical store.

Disintermediating traditional retailers — and forcing brands to decide how to become part of Amazon’s ecosystem or risk losing sales.

Over time, Alexa might also be able to help with this sort of request: “Alexa, I remember searching for a pair of white linen wide-leg pants a few days ago. Can you find them for me?”

At which point she does so, pops the picture onto the screen, and then allows me to place the order. All while delegating the tedious and time-consuming task of surfing the web while I’m multitasking — making dinner, getting ready for work in the morning or writing my Monday column.

Disintermediating traditional search — since Alexa becomes the consumer’s proxy for how search happens on and off Amazon.

In these use cases, Amazon plus Alexa plus Echo plus Echo Look plus Knight could deliver the best of what physical retail has to offer — plus the endless product selection that online has to offer — and at the total discretion of the consumer. The store and the brands come to her via a medium she likes and uses and from a brand that she trusts and increasingly uses to buy the things that she used to trek to a store to buy — 24/7/365.

Take a look at this chart from Statista:

It presents the results of a survey of 762 consumers done over five days in March 2017. More than half (56 percent) visit Amazon at least weekly, with 17 percent saying that they visit Amazon daily.

That’s astonishing, particularly since this was a random week in March and not around a holiday where shopping and gift buying could skew the results.

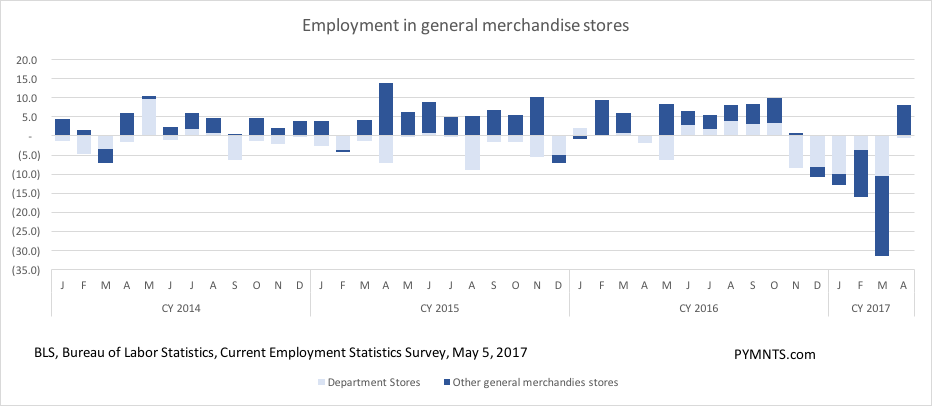

Now take a look at this chart, which shows the change in retail employment over the January 2014 to April 2017 period:

It paints a sobering picture for retailers.

Despite the robust job numbers reported last week by the U.S. Department of Labor, retail employment remains in a deep funk, accounting for only 2.8 percent of all jobs added. Department store employment has stayed flat, a stat that is somewhat misleading given the loss of nearly 60,000 jobs in the sector earlier this year and ongoing losses over the last several years, as this chart illustrates. Consumers aren’t walking into physical retailers like they used to and buying stuff from them, so retailers don’t need a lot of people to staff stores they don’t operate any longer or to service consumers who’ve stopped shopping with them.

It’s also reflected in the steep and steady decline in physical retail sales, despite physical retail’s best efforts to bolster online sales.

In its last quarterly earnings call this past February, Macy’s told investors to expect a year of declining sales, after reporting a more than 2 percent drop in sales year over year. It was the company’s sixth consecutive quarter of declining sales. We’ll see what happens on Thursday when it reports Q1 2017 earnings.

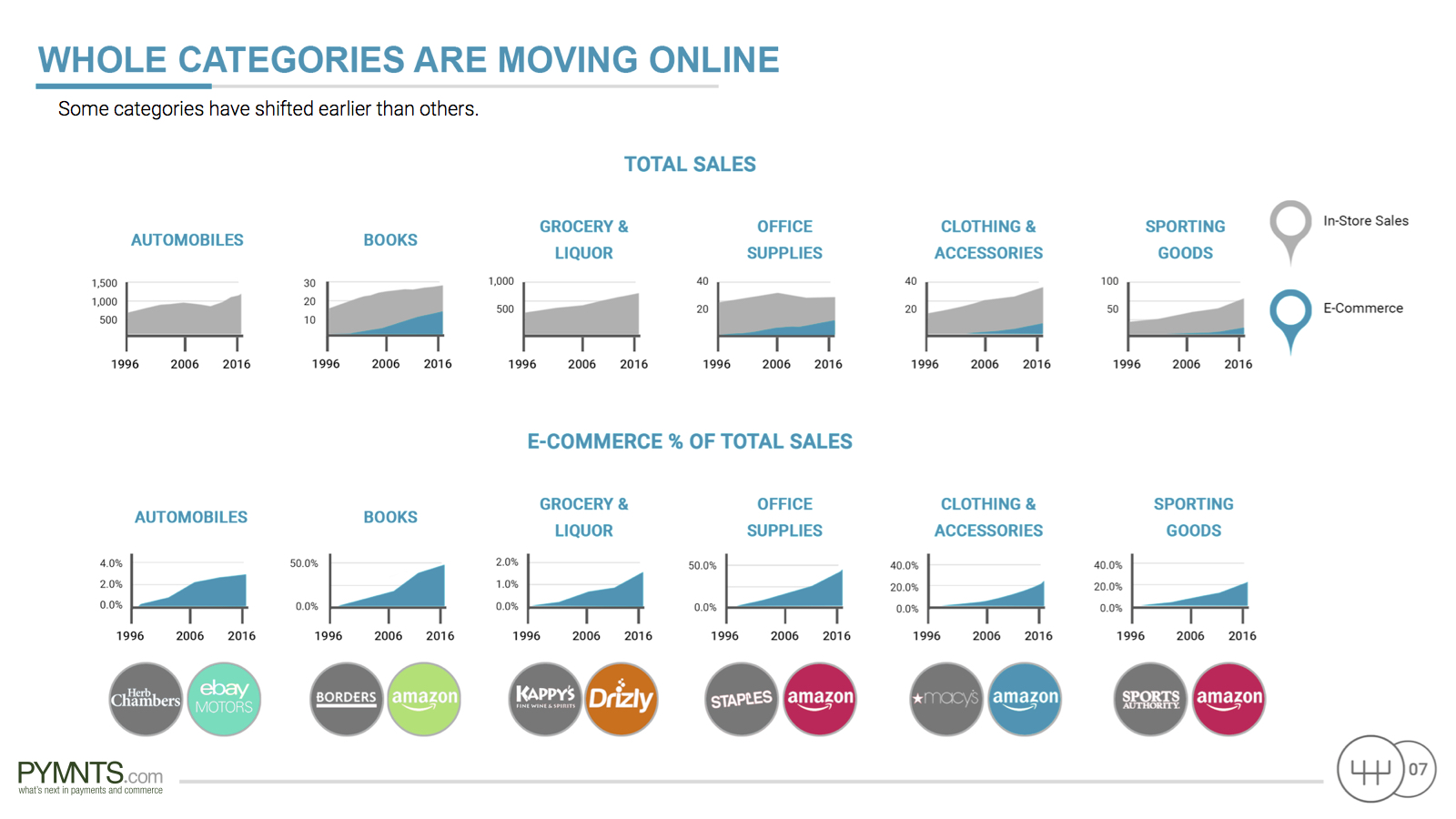

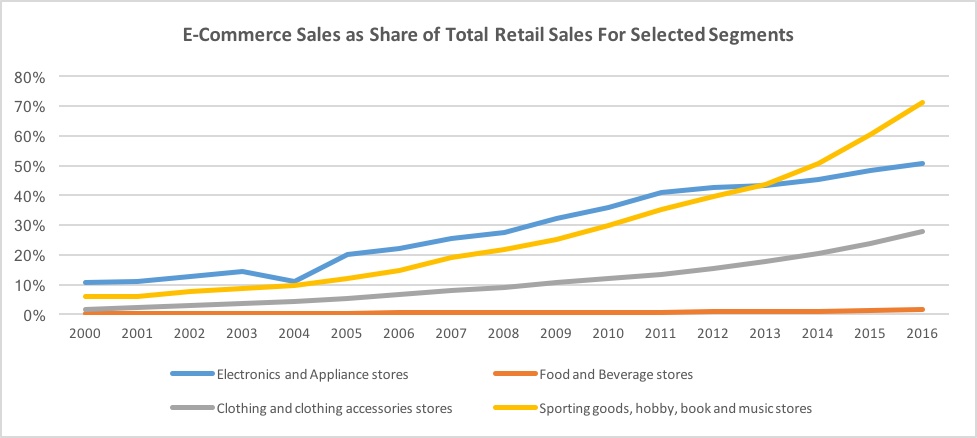

Now take a look at this chart, from work that the PYMNTS.com Data Analytics group did documenting the shift in sales online in important retail categories:

If you’re a traditional retailer, this won’t make your day.

Whole categories of retail are shifting online — and at an accelerating clip.

Online book sales are nearly 50 percent of all book sales. Office supplies are the same story. Sporting goods are approaching 30 percent, as is apparel.

Most of this shift started to hockey-stick in about 2012 — even using census data on retail sales that we know understates by as much as a third for the past 10 years the impact of online to physical retail.

Yes, starting five years ago:

Source: PYMNTS.com 2017

Five years later, it’s like watching a set of retail dominos fall, category by category, as Amazon captures more and more consumer spend by making it easier for consumers to start — and end — their search for what to buy with them.

It also explains why a player with less than 4 percent of all retail sales in the U.S. (we estimate 3.7 percent excluding auto and factoring in the gross merchandise value of Amazon’s marketplace sales) has made such an impact on retail overall when, since as everyone in physical retail still likes to say, 90-plus percent of retail still happens in a physical store.

Amazon’s 3+ Percent Retail Tipping Point

Book sales were retail’s bellwether.

Amazon picked books to start since it was a product that everyone buys. Over time, it’s shifted the purchase of books online by making them easy to buy and offering a vast selection, including their own “private-label” books published by their own publishing operation.

It blew a big hole in physical booksellers’ sales, shrinking bookstore’s retail footprint dramatically when it had less than 20 percent of that market a decade or so ago.

Today, at more than 40 percent of all book sales and nearly two times that of online book sales, no one in their right mind would even think about opening a book store, unless for the sheer love of books — and then, only as a hobby. And as an independently wealthy hobbyist, at that. With the opening of its Amazon bookstores, Amazon will compete vigorously with Barnes & Noble, the last retail bookstore chain standing, and probably independent bookstores, too.

Amazon’s retail Swiss Army knife has been taking shape for the last two decades.

Today, it’s an enormous marketplace that gives consumers lots of choices about what to buy. Products from third-party sellers are roughly 50 percent of all units sold and increasingly include name brands and designers such as Stuart Weitzman, Michael Kors, Tory Burch and even Gucci. Amazon’s growing stable of private-label products from consumables to apparel expands that product set even further — and at better margins for Amazon.

Amazon’s invested in logistics, including deals with post offices around the world, to get those products to consumers quickly and in many markets the same day.

Amazon’s one-click payment eliminates the friction from buying online and has expanded to include a growing number of third-party sites and its own physical locations.

Its co-branded card products deliver rich rewards for shopping on Amazon — 5 percent cash back on the Visa Chase product, for example.

Amazon’s removed consumer uncertainty over buying from it by offering the lowest prices — and proving it — by giving consumers visibility into the discount from the list price, along with product reviews and recommendations.

It’s put some purchases on auto-pilot by prompting recurring orders on items that lend themselves to being refilled in a specific period of time.

It’s done all of that by competing in categories where Amazon can most easily leverage the commoditization of retail merchandising and in categories and products that most people buy: sporting goods and clothing and apparel.

I did a search for the Nike Air Relentless 6 Running Shoe while writing this piece and found quite a few places that carried them — all very nicely presented in the Google shopping carousel. But right below that display was an ad for Amazon, showing multiple colors and price points. It wasn’t a hard choice for me to click that link and, in less than two minutes, put a pair in my cart, buy them in one click and have a Tuesday delivery confirmed.

With addition of its latest set of tools — Amazon Alexa, Amazon Echo, Amazon Echo Look and Amazon Knight — Amazon has the capacity to deliver the one thing that consumers say they still value from the physical retail experience: personal service and recommendations from a trusted sales associate.

Who happens to be named Alexa.

The Consumer’s Indispensable Amazon Retail Swiss Army Knife

Physical retailers have it tough today. Their business model and big investments in real estate make it hard for them to adjust to the new set of online retail expectations that consumers now have and the competition that Amazon has created as a once digital upstart.

It’s also not clear that physical retail can adjust in a timeframe that’s relevant to its own survival or that it should even try to do anything more than milk the asset at this point. The risk it faces is one even greater than Amazon’s stealing share — it’s being shut off by the brands that it once counted on for sales and foot traffic in stores.

Those brands just aren’t there anymore — or if they are, they’re offered in very limited supply, giving consumers one less reason to visit and brands even more of one to follow those consumers where they now shop.

Amazon.

But it’s not only the future of physical retail that’s up for grabs.

Amazon’s retail Swiss Army knife includes tools that give FedEx and UPS a big headache as Amazon builds out its delivery expertise. Digital wallets are getting one now, too, since they realize that penetrating the Amazon payments fortress is largely impossible. Brands will develop one over time as Amazon hones its manufacturing capabilities and becomes a private-label competitor. Tech giants like Google and Facebook are no doubt getting migraines as the competition over ad dollars will only intensify as Amazon uses tools like Alexa, Echo and Knight to concentrate even more search via its now growing and very contextual commerce platform.

Amazon also has two other big and very powerful tools that are part of its retail Swiss Army knife.

One is the consumer who likes and uses Amazon.

When consumers want to buy something, our research shows that more than half the time, they start with Amazon. Every eCommerce platform that’s tried to compete with Amazon head on has failed to get any traction — from eBay to ShopRunner, which made its deliberate shot across Amazon’s bow with free shipping across all participating merchants. Walmart and eCommerce site Jet.com are making a run for it, but it remains to be seen whether Marc Lore, with Walmart behind him now, can pull it off. Jet.com wasn’t exactly crushing it as a standalone entity and has a long way to go to match Amazon in terms of site utility and product depth and breadth.

The other is investors.

It’s been the topic of longstanding debate why investors were happy to look the other way when a 20-year-old company failed to produce operating profits — and consistently operated tens of billions of dollars in the red.

This is why.

Investors bought into the notion that it was OK for Amazon not to make profits but instead to make big investments in redefining retail for a digital world. Amazon makes profits today from its cloud operation and from retail verticals where there’s a lack of viable competition off Amazon, like books, and it can drive a growing majority of consumer spend.

It only took 10 years for Amazon to totally change how books are bought and sold. The question for traditional retail is whether it’s at the halfway point and, if it is, what it’s going to do over the next five years to change an otherwise inevitable outcome.

And if it isn’t, and if Walmart can’t pull it off, who — if anyone — will capture a significant share of retail as the move from offline to online storms on?