Consumer Shopping Data Shows Troubling Signs For Grocery Stores’ Future

Will Grocery Stores Go the Way of the Department Stores?

If grocery store executives want to see what their industry could look like over the next decade, they might want to look at how department stores have fared over the past two.

Like the department store brands did in the mid-2010’s, I am sure that grocery store execs look at Census Bureau numbers that show online grocery store sales as little more than bupkis and feel smug. Why wouldn’t they? Data, including ours, show that 93% of U.S. consumers walked into the grocery store at least once in the last 30 days to get food for themselves and their family.

Unfortunately, just like department store CEOs once did, these grocery store execs will soon feel the pain of death by a thousand cuts as consumers buy groceries just as they purchase any other retail product — gradually moving those purchases online and to specialty physical retailers with a more curated and relevant selection of the items they once bought at the grocery stores.

Many consumers have already begun the shift. Food inflation may be keeping grocery store sales high, but when adjusted for inflation, aggregate grocery store sales have declined slightly over the last two years.

There are increasing signs of the thousand cuts taking blood.

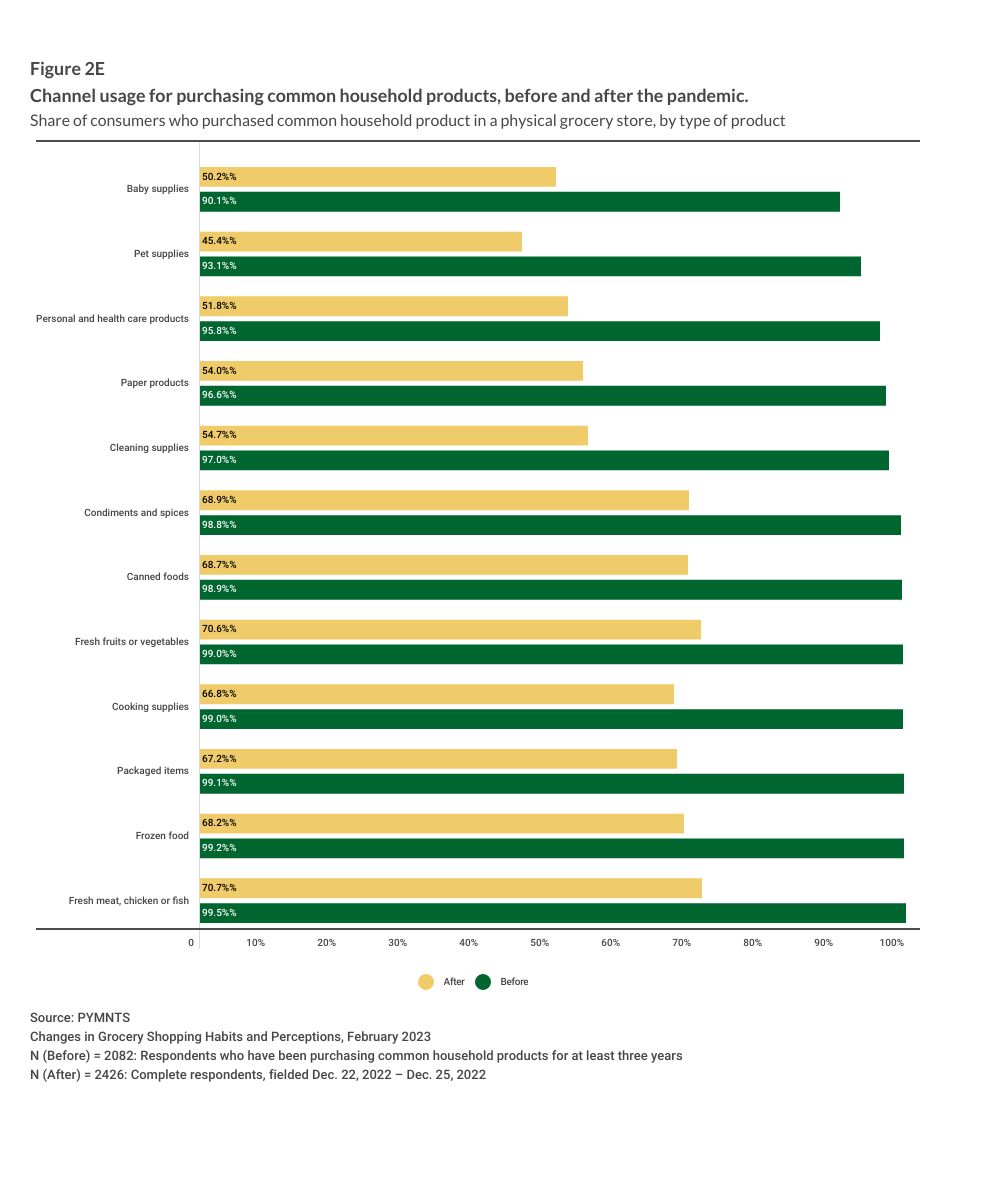

PYMNTS data shows that three years ago, nearly every single consumer who bought at least one common household product each week — the items that occupy the center aisles of those stores such as paper towels, cleaning supplies and canned goods — did so at the grocery store.

Today, 22% fewer consumers across all grocery product categories report that they still make any of those purchases in the store.

As we start 2023, fewer than half of all consumers report buying 50 percent or more of those center aisle grocery store purchases at the brick-and-mortar grocery store. More than a third of consumers (37%) now say they purchase none of these grocery products from a brick-and-mortar grocery store — up from 2.2% in 2020.

It’s a stunning shift in just three years.

Digital is where a growing number of grocery shoppers are turning. Apps, websites and delivery aggregators make it easier to shift the consumer mindset away from the ten-minute drive to the grocery store and toward whatever platform quickly lets them find what they want and need to buy. The share of consumers who now buy at least one household product online increased 23% over the last three years.

Consumer concerns about running out of essential household items also accelerated the growth of the refill economy. PYMNTS data show a growing share of that digital shift results from an increase in subscription services across nearly all classic grocery store product categories. That includes Amazon Subscribe & Save. Purchases of both canned goods and cleaning supplies by subscription increased at least 35% over the last three years; purchases of baby products by subscription grew 77% over that same time.

High earners, millennials and Gen Z are the early adopters of online grocery store shopping. That’s probably not much of a surprise. What is more unexpected — and should have grocery store CEOs worried — is the consistent shift away from grocery stores to digital channels by every demographic group for every single grocery product category.

Everyone from the struggling paycheck-to-paycheck consumers to the middle income households to the Baby Boomers are shifting their grocery purchases online.

For most U.S. consumers in 2023, buying groceries doesn’t necessarily mean buying them at the grocery store anymore.

What’s a Grocery, Anyway?

The pandemic forced an across-the-board reset of how consumers define “groceries” and decide where to buy them. Supply chain shortages and fears about going into a store forced consumers to find alternative sources for the products they needed to stock their pantries, kitchen cabinets and refrigerators and feed their families.

In 2020, PYMNTS data showed that nearly 80% of consumers categorized canned goods, cooking supplies, condiments and spices as grocery products; today 60% do. Twenty-four percent fewer consumers now regard health and beauty products as grocery items to pop into their cart as they cruise the grocery store aisles.

That mindset shift has had a discernable impact on where consumers now go shopping for the items that once filled their grocery store carts.

In 2020, nearly all consumers bought at least some of their canned goods, condiments, spices and cooking supplies at the grocery store. In 2023, a third fewer consumers say they make any of those purchases there. Three years ago, nearly all consumers bought at least some of their cleaning supplies at the grocery store. Three years later, the number of consumers who say they do has fallen sharply, by 44%.

Just as department stores saw over the last three decades, the shift away from “groceries” bought at the grocery store to an eCommerce purchase for nearly every grocery product category was accelerated by the ease, convenience and certainty of buying important household products online. PYMNTS data shows that convenience is why nearly two thirds (62%) of consumers buy fewer things at the grocery store and more online; 54% cite higher prices and fewer deals at the stores they used to shop.

Just like the decline of department store sales, the shift away from grocery to other channels and providers has happened sharply in important product categories as consumers searched and then found cheaper, more convenient and more predictable places to shop.

In 2020, shoppers who bought pet supplies and baby products from grocery stores were starting to shift to other sources for some of those purchases. Three years later, the share of consumers who buy pet supplies and baby products plummeted. Today, roughly half of consumers who buy pet and baby supplies now report buying absolutely none of those items at the grocery store.

The Grocery Store Marketplace Dynamic

Unlike department stores in the mid-2010s, most grocery stores today have an online presence — that channel puts them less at risk of losing sales to the digital natives and marketplaces that hobbled department stores over the last two decades.

Or does it?

Instacart is the largest grocery store marketplace in North America. The company powers eCommerce for more than 1000 grocery brands and 75,000 stores across North America and has given grocery stores the digital leg up to stay competitive in a retail environment that is moving more digital.

Instacart has also created a more competitive grocery market at the same time it has given grocers a way to be digital in a digital-first world. With Instacart, consumers are no longer constrained by how long it takes to drive to and from the store. As they like to remind consumers at the end of each online shopping trip, shopping with Instacart saves consumers 2 to 3 hours with each order.

That has changed consumer behavior and grocery store dynamics. Shoppers can swap a more local location for the grocery store with better prices and a bigger selection that was out of driving range for delivery. They can divide their grocery shopping “trips” without having to actually spend the day driving to and from multiple stores to get exactly what they need to buy for the prices they are willing to pay.

The other marketplace dynamic that grocers must contend with is the growing relevance of Amazon Subscribe & Save and the importance that brands place on that channel. More than 182 million consumers have an Amazon Prime membership and used it to drive $478.5 billion in eCommerce sales in 2022. Amazon Prime Members are prompted to turn almost every purchase into a Subscribe & Save opportunity, something that 7.2 percent of U.S. consumers have done to purchase the household items that once filled grocery store shopping baskets. Subscribe & Save, along with other subscription offerings, gives brands a more competitive opportunity to make a sale, then lock a consumer into a recurring purchase over a long period of time.

The Grocery Store Foot Traffic Problem

If you’ve shopped at a department store lately, chances are you’ve probably had the whole store to yourself. Foot traffic is down significantly, including over the important holiday shopping season. Analysts reported that over the five days between Thanksgiving and Cyber Monday, foot traffic was well below 2021 and 2019 levels at both department stores and malls.

Consumers have found better and more efficient ways of shopping that don’t include department stores. Consumers shop online, they shop at smaller stores in their local cities and towns, they shop at discount retailers and at specialty retailers with a curated mix of products more consistent with their needs. This all happens without consumers really spending any more of their time shopping. Technology, including buying online, has given consumers the ability to divide shopping into the things they need — the utility purchases — and the things they might like to buy — the social/discretionary purchases — and given them a greater certainty in purchasing both.

Over time that has meant fewer feet in department stores, which has resulted in fewer brands willing to spend the money and effort to have their merchandise there. The network effects in reverse have made department stores a less attractive place to shop and a less valuable venue for brands to display their merchandise.

Grocery stores may be staring down a similar dynamic.

In 2006, consumers took about 2.1 trips to the grocery store every week. By the end of 2022, the number of trips declined by 24% as consumers shifted shopping channels online and to other retailers, including discount stores and warehouse clubs. At the same time, the mix and number of items that consumers bought at those grocery stores shifted too. PYMNTS data shows that food inflation prompted roughly 70% of U.S. consumers, including 64% of high-income consumers, to trade down to lower-cost items and/or adjust the number and types of items in their grocery basket to stay within their household budget.

The typical grocery store has 30,000 to 40,000 SKUs. Keeping store shelves stocked is important if grocery stores want to keep consumers shopping and buying there. Doing that while fewer feet visit less often and buy fewer items could create the same department store downward spiral as consumers find other places to shop. At some point it won’t make sense for stores to stock certain categories of SKUs such as pet food, or for brands to devote resources to managing the shelf space. That will create even more of a downward spiral.

The Future of Grocery Stores

The grocery store innovation, like its department store counterparts, was giving consumers a single place to buy what they wanted. As important, these vast physical showrooms gave consumers the chance to physically inspect — to touch and feel — the items they wanted to buy before making the purchase as they browsed the stores. A century or more ago, items were kept behind a counter and consumers had to ask a sales associate for help. Department stores and grocery stores removed that friction and made shopping easier and more convenient.

In 2023 and in the years to come, the single place for consumers to buy — or at least start their search for what to buy — is their laptop, mobile phone or voice-activated connected device. This is how consumers will find deals, see if what they want to buy is in stock, and set and forget the purchases of the things they buy all of the time and don’t want to run out of.

The future of grocery shopping isn’t all digital, just as it isn’t in any other part of retail. But neither is it an entirely physical store experience either. Consumers, all consumers, see the physical grocery store experience as a smaller slice of how they shop for groceries.

Technology and embedded payments will give consumers the personalized and specialized shopping experiences they want with an easy way to make the purchases. Consumers will be able to shop online at their favorite store or find their new go-to — or find specialty shops online and then buy from them in their physical stores.

This is a trendline that department store executives largely ignored as smartphones and apps introduced consumers to new places to discover — and digital payments and wallets gave consumers new ways to buy the things they once bought in their stores. The mobile devices and web browsers became the consumer’s department stores. The decline began in the early 2000s with the rise of the web and accelerated in the 2010s with the proliferation of smartphones and apps. Department stores have never recovered — and they likely never will.

The grocery store future doesn’t have to end the same way. Grocery stores can avoid this fate by paying better attention to the data about consumers and their shopping trends in 2023 instead of repeating the mistakes of departments stores that looked at consumers, data and retail trends in 2010 and thought they were invincible.