How Airbnb and 18th-Century Newspapers Found Profits from Frictions

Brian Chesky says that Airbnb is broken and he’s going to fix it.

New York City recently passed regulations that all but gave them the boot. Meanwhile, guests are griping — such as when they find, after a long trip, that the place they rented doesn’t exist or they get a surprise cleaning bill after they’ve done double-duty as housekeepers. Hosts, many of whom are making a living from renting and not just sharing the spare coach, are looking to make more money from their properties.

Investors must not be worried too much, given that Airbnb has a market cap of about $80 billion. So long as NYC isn’t a bellwether for other major cities, their problems seem fixable. Some reflect the tension many platforms have between multiple stakeholder groups and regulators.

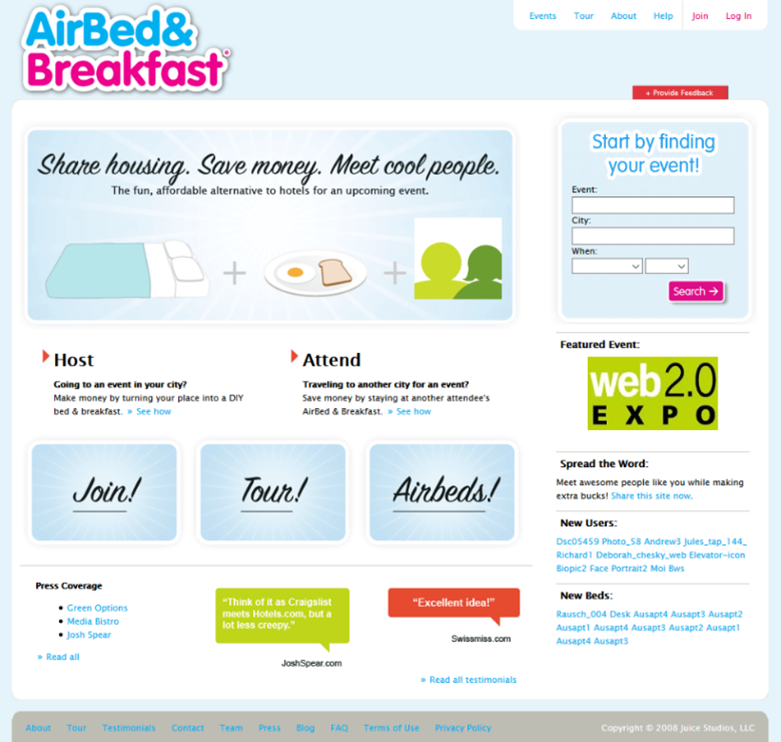

Airbnb started as a “friction fighter” in 2008. It provides important lessons to entrepreneurs, investors and corporates searching for opportunities to make their fortunes during the digital transformation.

To understand where they should look and to size up the potential, let me begin by knocking the company Chesky co-founded down a bit.

Not a New Product

Airbnb didn’t really invent a new product. People have been letting rooms and looking for places to stay for a very long time — probably almost as far back as people stopped sleeping on the ground and put roofs over their heads. Some of these were likely for short-term stays and for travelers.

It wasn’t even the first matchmaker for getting hosts and guests together at scale.

Print newspapers started sprouting up in the mid-1600s and started selling advertising by the end of the century. In London, newspapers became wildly popular during the 1700s and chock full of ads.

Those included blurbs for rentals of rooms for the day, week or month. Anyone looking for a place to stay just had to scan the newspapers to find a room with accommodations for a horse or with a widow looking for some extra income.

Those included blurbs for rentals of rooms for the day, week or month. Anyone looking for a place to stay just had to scan the newspapers to find a room with accommodations for a horse or with a widow looking for some extra income.

This new channel of communication eliminated a lot of the friction —including boot leather — for people looking for rooms for people with rooms to let. Instead of just posting “room to let” in their windows, landlords could reach a wide population and guests could save time trying to find one. Although there was already a well-established market for letting rooms, newspaper ads made it far more efficient by widely disseminating information on available inventory.

Hundreds of years later, classified ads in newspapers, and eventually Craigslist and other internet-based publications, became the mainstay for short- and long-term rentals. Rental agencies and other matchmakers emerged, but they relied on newspaper and magazine ads to spread the word.

So Airbnb didn’t really invent a new product. People have been subletting rooms and searching for places other than hotels to stay for as long as people decided there were better options to sleeping outside.

Airbnb also wasn’t unique in creating a communication channel between buyers and sellers. Nor was it the first matchmaker to help people find a place to rent for a couple of weeks in Tuscany or the Hamptons.

Century-old ads show that Airbnb wasn’t even the first to deal with trust and payments. Reciprocal references and cash may have done that for centuries.

Starting a Friction Fighter

So, what’s with the $80 billion?

Airbnb’s innovation was recognizing that the existing market for short-term rentals was rife with frictions that could be reduced with new digital technologies and new business models made successful by previous digital pioneers.

The company didn’t have to create a new product. It “just” made an existing market, with many active buyers and sellers, work far better. And it sure did.

This is an important point with practical implications for every innovator,

Some inventions seem to come from nowhere, sprung from the mind of a genius. At least that’s how we think of them after they’ve succeeded. The fact that there are often several pioneering thinkers chasing the same idea around the same time doesn’t change the point much. Almost by definition, it would be impossible to give the person who won the race to create the new thing, such as electric power or calculus, an instruction manual on how to do it. Although I’m sure if I looked on Amazon, I would find some with 4-5 star reviews.

But when a market already exists and fundamental innovations have already been made, there’s a greater opportunity to use research, data and analysis to find pockets of untapped profit opportunities. And that’s the focus of many successful modern-day digital entrepreneurs.

They start with a traditional industry that helps connect two types of users so they can enter into an exchange that benefits them both, like marketplaces. Or one in which people benefit from getting together to improve how they find people or products or the perfect mate, like dating apps or social media platforms. Or an industry that helps make those pecuniary or non-pecuniary exchanges easy and secure, as payment cards do.

These entrepreneurs then unpack the process of interactions in the market to identify “frictions” that impose financial or psychic costs on one party or both. Some of these transaction costs may be so severe that they prevent exchanges from occurring at all, so reducing them enough could increase the market size and provide new revenue opportunities. Other sands in the transaction gears may just be taxes on the participants — the two sides may be able to find each other and transact, but less value is exchanged between them because some is lost to frictions. Market participants will pay to reduce these costs.

Finally, they have to figure out solutions — which could be based on using off-the-shelf tools applied to other markets — for eliminating or reducing these frictions. That is ultimately where their creativity in developing solutions and their ability to develop a business that can execute on bringing these solutions to an existing market is paramount.

They are friction fighters.

The potential profits to be gained from being a friction fighter depends on the size of the market, the impact of the frictions, the ability to reduce those frictions and the potential for expanding the size of the market from doing so.

The physical economy has pools of these potential profits, of all sizes, ready to be drilled by anyone who can find them, solve the friction points, and ignite a profitable business. Subsequent posts will elaborate on the FIT® Framework, introduced by Karen Webster, for maximizing the odds of success.

The Lessons to be Learned

The original Airbnb was a matchmaking service for hosts and guests. But using digital technologies, one with far more potential for creating dense markets of hosts and guests by aggregating supply in a city and making it available globally. Airbnb then worked its way through the other frictions — such as ensuring the quality of host properties and guaranteeing payments by guests.

Next week, we’ll drill down into the varieties of frictions to look for and the obstacles that can turn a promising friction-fighting machine into a predictable heap on the ground.

The trick is finding markets with solvable friction problems that don’t face other insurmountable obstacles for success.

David S. Evans is an economist who has published several books and many articles on the technology businesses, including digital and multisided platforms, including the award-winning Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. He is currently the Global Leader for Digital Economy and Platform Markets at Berkeley Research Group. For more details on him, go to davidsevans.org.