What Lighting a Fire Has in Common with Platform Ignition

You need three ingredients for a fire. Oxygen — if you don’t have that you are really in trouble. You better bring a match or a flint, unless you are really skilled at creating sparks. And you’ll need to gather tinder and logs.

After that, it’s all physics. Energy is released when you light the tinder. Then, in a chain reaction, more energy will be released, and the pile will combust. You’ll have a raging fire that will keep you warm and heat your morning coffee. But only if — and these are big ifs — you’ve gotten wood that can burn well, arranged the tinder and logs in just the right way, and made sure the oxygen can circulate to fan the flames.

The fire will keep burning as you add more logs because it generates more energy than it consumes. A reaction that creates more energy than it consumes is called an “exothermic process.”

It turns out that igniting a platform business and igniting a fire sort of follow the same physics.

Consider a simple three-sided delivery platform with restaurants, drivers, and consumers. Those participants are the essential ingredients. Just like combining fuel and oxygen, the platform founders have to start with them. And not just any participant — they have to be the restaurants and the consumers who are likely to want to do business with each other and drivers who will provide timely and reliable delivery. In platform economics, that’s usually called “getting the participants on board” or solving the “chicken-and-egg problem.” (Don’t worry, we won’t mix analogies and rotisserie chicken.)

Advertisement: Scroll to Continue

Then, the founders have to “light” the platform by getting those participants to interact with each other. For the delivery business, that means people ordering food, restaurants preparing it and drivers picking it up so that the early adopters of the platform start getting value out of it.

After that, the founders must fan the flames to get a chain reaction. They must get more participants on board and get them to interact more. Some participants will lose interest or stop using the platform just like a fire initially sputters and may die out. Some restaurants might drop out because they aren’t getting enough volume to justify the hassle of participating, and some consumers might get bored with the restaurant selections.

The founders should power on until they reach a “critical mass” of participation and interactions. That’s when a chain reaction kicks in and there’s combustion. The platform ignites when it reaches this point where the platform, in an exothermic reaction, generates more energy than it consumes.

At ignition, the platform starts attracting more participants and activity than it loses from attrition because the network effects between participants become so powerful. Restaurants join because the platform gives them access to a lot of consumers, drivers to a lot of jobs and consumers because they can get a good selection of meals delivered reliably to their homes.

Entrepreneurs, corporates and investors can learn more about the art and science of platform combustion from my article on igniting new platform businesses and my book on the economics multisided platforms with Dick Schmalensee. (Dick and I also have a technical article on the dynamics of platform ignition for math nerds).

Unfortunately, launching a platform is far harder than starting a blazing fire.

The mountains would be littered with frozen corpses if backpackers were as successful at starting fires as founders were at igniting platforms.

You’d think that there’s nothing like experience, though. It is, therefore, surprising to see Facebook flail with Threads and a bunch of Silicon Valley billionaires think they could start a city from scratch.

Threads Flubs Ignition

Meta saw an opening as users and advertisers deserted X following its acquisition by Elon Musk on Oct. 27, 2022. X’s flame has hardly gone out, but the global number of app users has declined by 16% and U.S. ad revenue has fallen by around 60% since it was sold.

The economics of ad-supported microblogging platforms like X are straightforward. A minority of users post blogs or comments and thereby generate most of the content. Most people don’t do that so much, but come to view the content created by others. There’s a positive feedback loop: content creators value a platform that has more viewers because they want to be influential and users value a platform that has more content creators they like.

The platform makes money by selling ads to companies that want to message the users. There’s another positive feedback loop: more content attracts more viewers, which attracts more ad revenue and more ad revenue funds operating and investing in the platform. These related positive feedback loops can result in a chain reaction and self-sustaining growth.

Through a number of intentional changes, new X management weakened these positive feedback effects, much like depriving a fire of oxygen.

Meta adopted, what it appears to have thought, was a winning strategy to create a new X rival. It leveraged its Instagram social network, which has about 2 billion monthly active users globally.

Instagram users could use their credentials to sign into the Threads app (which they had to install) and then instantly follow their social network on Instagram. Threads had more than 100 million sign-ups in less than a week, even though it wasn’t available in the EU to start.

The problem was that these Instagram users did not have much motivation to post microblogging content. Furthermore, while their connections on Instagram might be interested in seeing pictures of their dog doing tricks, they weren’t the right people to share opinions or news. Meta did not appear to have a strategy to get account holders to engage in microblogging.

Meta might have thought that getting a massive number of account holders could only help. That’s not necessarily true for the same reasons that piling a lot of logs without tinder or oxygen can’t start a fire.

Users who check out Threads weren’t likely to see content they’d be interested in. The longer that went on, the less likely they would be to come back to Threads. Meanwhile, content creators are less likely to post because they don’t have an engaged audience.

Threads now has almost 140 million people account holders. Instead of providing the foundation for a chain reaction, however, those about 140 million people have learned that Threads is not a useful microblogging site for them. Many customers will no longer be fuel for the critical mass needed to set off a chain reaction and ignite the platform. They also probably won’t recommend that their friends or acquaintances try this new X-rival.

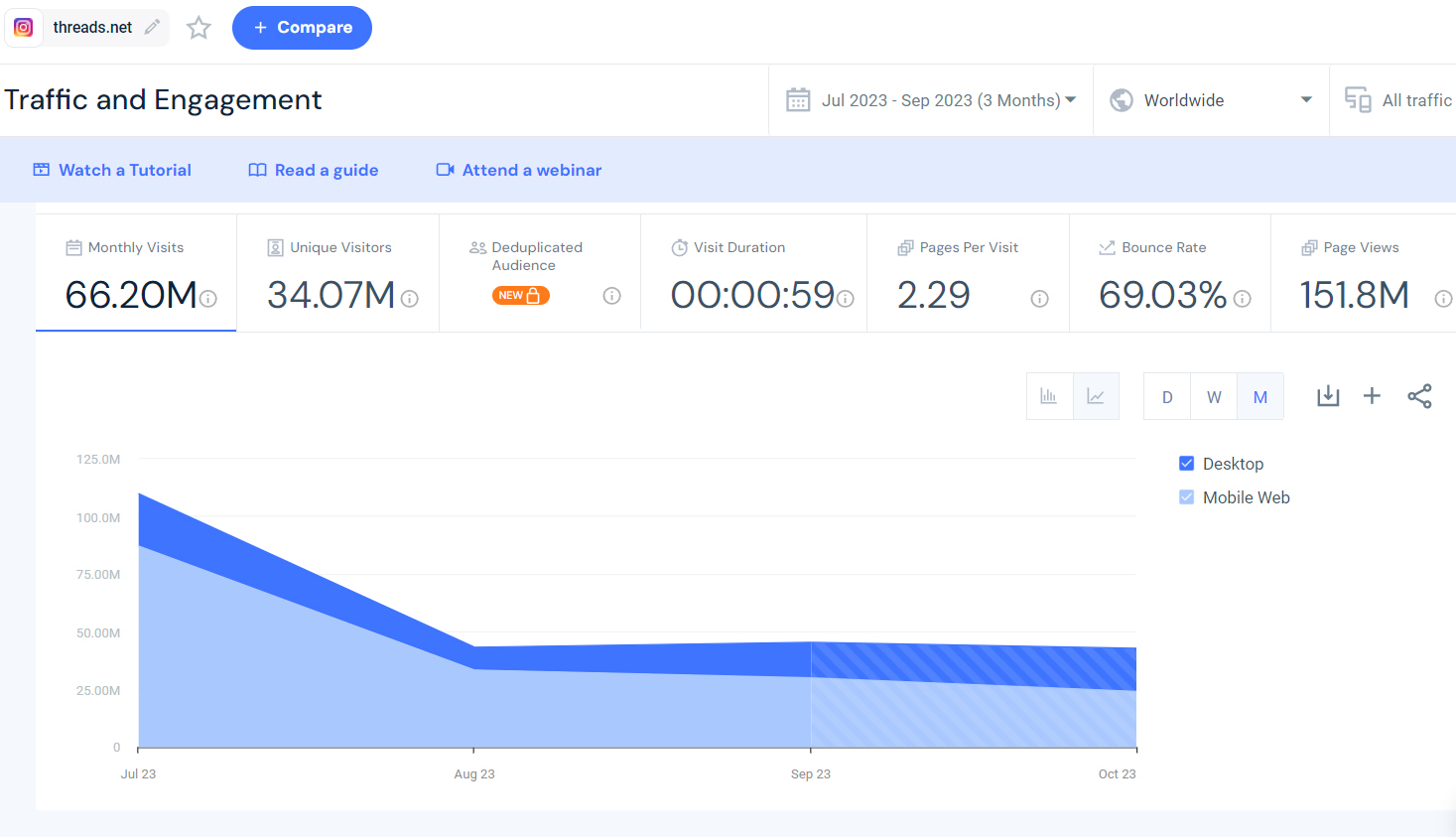

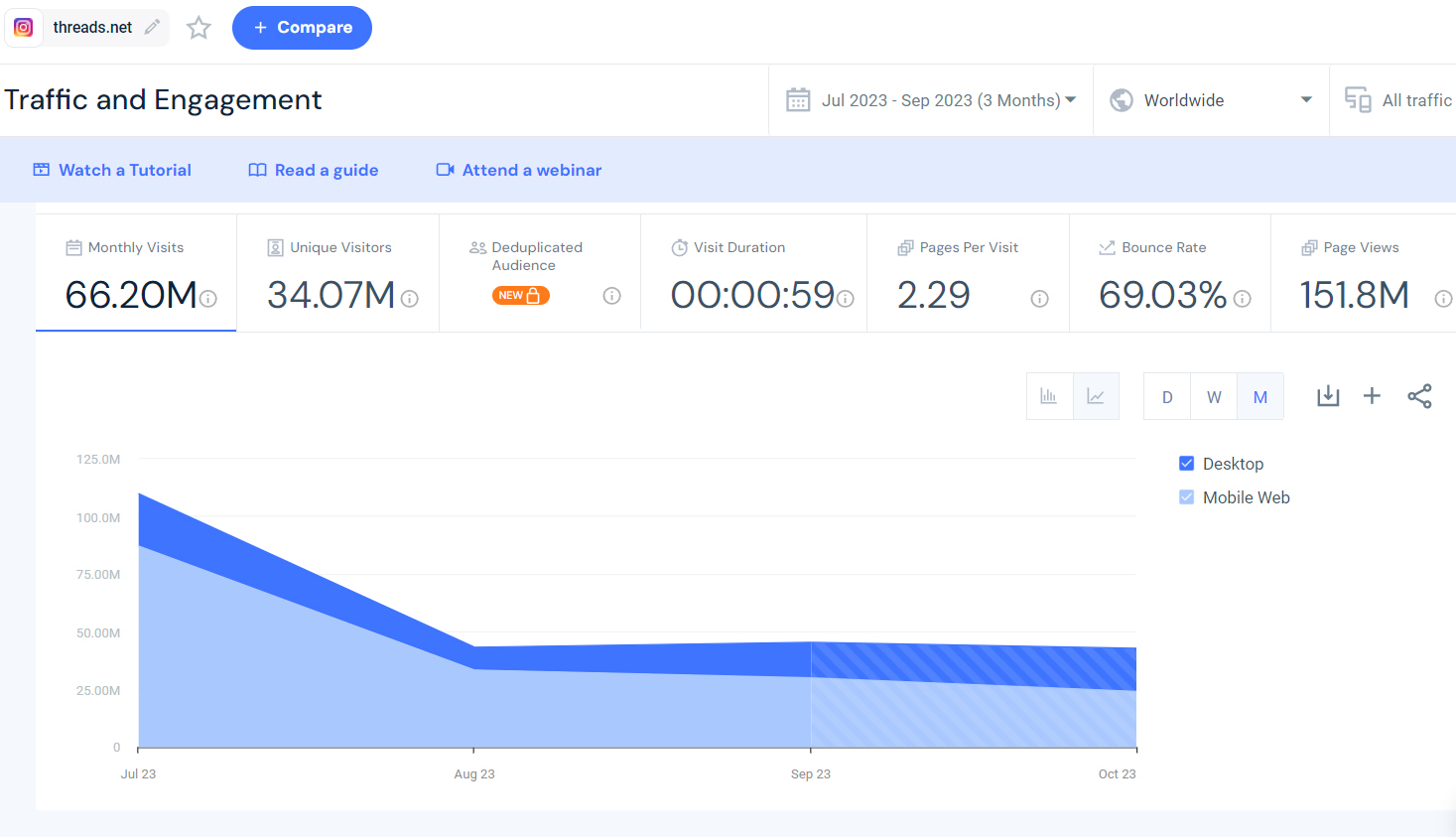

So far, the signs are quite bad. In July, the month of its launch, Threads had 109.8 million web and desktop visits, according to similarweb.com. By September, that had fallen to 42.8 million visits, a decline of 61 percent.

Mark Zuckerberg, who has a lot of practical experience with platform ignition, seems to have recognized the problem posed by lots of people having a bad experience on a platform. Yet his remarks on Meta’s latest earnings conference show a serious mismatch between how Meta launched Threads and what he says is the right way to do it.

“[W]e have a basic playbook here, which is build an experience. It’s got to be something that people like, so it has to have product market fit. Once you get that, it’s not always retentive. So a lot of people might like an experience, but you need to kind of tune it so with the numbers works that people who use it are continuing. We feel like we’re getting to a good place on that with Threads. There’s still a lot of basic functionality to build.

Once we feel like we’re in a very good place on that, then I’m highly confident that we’re going to be able to pour enough gasoline on this to help it grow once we get to the point where we feel good that everyone who’s using it is going to continue using it at a high rate. And then, in a few years, once we get to the point where it’s at hundreds of millions of people, assuming we can get there, then we’ll worry about monetization. But I mean, that’s basically the playbook that we’re focused on.”

Unfortunately, that’s not the playbook Threads followed.

The platform got a massive number of users signed up without apparently having any plan for getting them to interact much with each other. Now, Meta has a harder job to ignite a new microblogging site today than they did before they launched Threads in July.

It is really hard to get people to come back after a bad experience, just like it is hard to restart a fire that has sputtered with wet wood or not enough tinder.

If We Build It, They Will Come, So Say We

It’s audacious, for sure. A group of Silicon Valley billionaire entrepreneurs and venture capitalists and hangers-on plan to create a new city in California, beginning by buying up thousands of acres north of San Francisco. Just breaking ground is a long way off, so unlike Threads no one can say for sure that they can’t succeed. I’m sure that movie of their endeavor will be great, like Fitzcarraldo building an opera house in the Amazon, but I’d put the odds of it happening at about the same as the long-dead Shoeless Joe Jackson actually appearing in the Field of Dreams

As anyone who has been following major cities, post-pandemic, has probably figured out, the economics of platform dynamics fits them pretty well. Cities have several stakeholders who depend on each other. They need businesses to employ residents and commuters, businesses to service those people, and they need residents who want to live there or nearby. And they must have enough businesses and wage earners to tax to fund all the services people and businesses need from the city. There is a virtuous circle connecting all these participants.” When cities are in equilibrium, just kind of humming along, we don’t focus on how interdependent these stakeholders are.

Until there’s a debacle that upsets the equilibrium. Then, as we saw beginning in 2020, the chain reaction between the participants works in reverse. Fewer residents and commuters reduce the number and variety of service businesses. Those losses make it harder to persuade people to live and work in the city. Employers have less demand for consolidating office space in the city. And these negative vectors feed on each other. Since the pandemic largely subsided in mid-2021, cities have been recovering, but slowly, and it is not clear some will return to their former vibrancy.

Cities tend to agglomerate over time through the same sort of network effects that drive platform growth. People gravitate to cities where other people are, and so do employers. As all that happens, the number and variety of service businesses and other activities increase, which makes the city even more appealing for people. The process is slow because there are lags between improvements, people and businesses being confident in those improvements, and making investments and decisions based on them.

Starting a new city is massively more complicated than launching most platform businesses. To begin with, people or businesses located in a new city incur substantial sunk costs they won’t get back if things don’t work out. It is about as far from just clicking on a new platform, like TikTok or Threads, as you can get. City participants have to be very sure that the stakeholders they depend on will also show up. No one is going to open a new supermarket or restaurant without being sure that it will have customers.

Few people are going to buy new homes — assuming a construction firm took the chance of building some — without being confident that they’ll have places to buy groceries or go out to eat. And, of course, employers aren’t going to locate there and create jobs unless there’s a likelihood that there will be people to employ.

Doing all of this, at scale, to compete with other major cities for people and businesses appears mind-bogglingly difficult.

Maybe the SV billionaires can get Taylor Swift do all of her concerts there. Her Eras concert reportedly caused a minor earthquake in Seattle, but perhaps she could ignite a city if she channeled her energy, and raised her kids there.

The Platform Ignition Playbook

Platform ignition is far more complicated, messier and harder than lighting a fire. There is, though, a science behind both that can provide the basis for a playbook on how to maximize your odds of creating a blazing fire or igniting a platform. Even those who have started a fire or a platform can benefit from a refresher course.

That’s true even for billionaires who’ve done it before.

David S. Evans is an economist who has published several books and many articles on the technology businesses, including digital and multisided platforms, including the award-winning Matchmakers: The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. He is currently the Global Leader for Digital Economy and Platform Markets at Berkeley Research Group. For more details on him, go to davidsevans.org.